people are sacred, conversations are worship

— 達真 (@tasshinfogleman) October 14, 2021

I have been fortunate to be in multiple contexts where conversations were considered to be precious, an art form, truly and deeply transformative. These contexts were wildly different, and I learned different skills in each of them. These skills have fused into the approach that I bring to the conversations that I have on my podcast.

In this piece, I’ll reflect on my conversational influences, and the moves and skills I learned from each of them.

St. John’s College

The four years of my undergraduate education were, on the whole, one of the happiest periods of my life. I attended St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland (A’13).

St. John’s is a small liberal arts college. It has two campuses, one in Annapolis (not at the Naval Academy) and one in Santa Fe, New Mexico. There are approximately 500 people on each campus—half the size of my high school.

It has an all-required program. Everyone studies the same things. Specifically, you study the Western Canon or the “Great Books”: everything from Homer to Virginia Woolf, from Plato to Heidegger. The curriculum includes Philosophy, Literature, History, History of Mathematics, History of Science, Language, Music, and more. I graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in the Liberal Arts.

There are no tests or exams at St. John’s (save for a small handful of pass/fail quizzes that assess your progress in language, mathematics, and music theory, making you eligible to continue with the program of study). There are grades at St. John’s, but they are primarily offered for the sake of further graduate study, and they aren’t even sent to you. You have to choose to see what your grades are.

The program of study involves primarily three things: reading books, discussing them in conversation-based classes, and writing about the books you read.

Before I matriculated at St. John’s, I was excited to read and have read the Western Classics—to be able to discuss and consider the most important books of the Western World.

After having graduated from St. John’s, I can tell you something that would have surprised me: I don’t really care that much about it. It’s rare that having read major excerpts of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit is relevant to my everyday life or ordinary conversation. I haven’t once regretted not finishing the sole seminar reading I didn’t complete, because I decided it was far too boring and irrelevant to my life to waste my time on.

Instead, the skills I practiced at St. John’s have been far more useful to me. Reading. Writing. Listening. Speaking. Asking questions. Following my curiosity.

I’ve used these skills in my own independent studies, in my conversations and podcast episodes, in nearly every area and chapter of my life since graduating.

At St. John’s, reading and conversing are taken as art forms. There are some master learners there, who I learned very deeply from, from watching how they read, how they asked questions, how they listened, how they shared their thoughts in conversations.

There are a few specific conversational skills that I learned through conversations at St. John’s. Some are quite simple; others are more advanced; all of them have been transformative for me.

I thought it would be useful to articulate and share these tools. For the most part, these are names of my choosing, describing patterns I noticed in my own education—perhaps others would notice different patterns, or describe them differently.

- Opening Questions: starting a conversation with a question you’re genuinely curious about, that requires investigation and consideration (ideally with others who have the same context), rather than a thesis or a point that you already know or have already decided on.

- Ordering the Questions: proposing a logical order of the questions at hand and beginning with the first, proceeding through each question as able.

- Refactoring the Question: breaking up a larger question into smaller questions, or asking the simplest possible version of a question before advancing to the more complicated or complex questions. For example, ask what virtue is before you ask whether it is teachable (a la Plato’s Meno).

- Bookmarking Rabbit Holes: if there is a fork in the conversational road, making a decision about how to proceed while noting the alternate possibilities so that you can return to them if desired.

- Tracking Interruptions: if there are practical interruptions, or a conversational tangent, noticing that there was an interruption, remembering what was being discussed, surfacing to collective attention that there was an interruption when possible, reminding the group of the content of what was being discussed.

- Following the Line of Conversation to its End: noticing whether a question has in fact been satisfactorily answered, and refusing to be distracted by other interesting but unrelated questions until it has been answered. requires power from a leader (official or unofficial) and buy-in from the group.

- Lost Packet Recovery: occasionally, packets of information are dropped in conversation. You miss a word or a sentence or even a whole point that someone is making. There’s a move the listener can make of requesting the missing packet and specifying specifically which packet they are looking for. You can do this by repeating the parts you did hear (word for word, or in summary) in a tone that suggests you missed the other part. If the speaker knows what the listener is doing, they can briefly supply the missing packet and resume what they were saying. Without this skill, the speaker often defaults to repeating their entire sentence or point word for word, which is inefficient, and is increasingly annoying the more times it needs to happen. If both the listener and the speaker have the relevant skills—if they know that you can dance with each other in conversation to request and supply missing packets—it’s efficient and connecting. This is similar to the way that two people knowing the same dance moves or playing the same sport is connecting and fun.

Circling

I learned to practice Circling at the Monastic Academy. Circling afforded me an opportunity to bring my mindfulness and meditation practice into a social setting, to connect presence of mind with spoken interactions and community.

Being able to discern my own experience, and listen to the words and expressions of others, with wisdom and love, consistently created experiences of mutual understanding, deep intimacy and connection, and sometimes radical transformation.

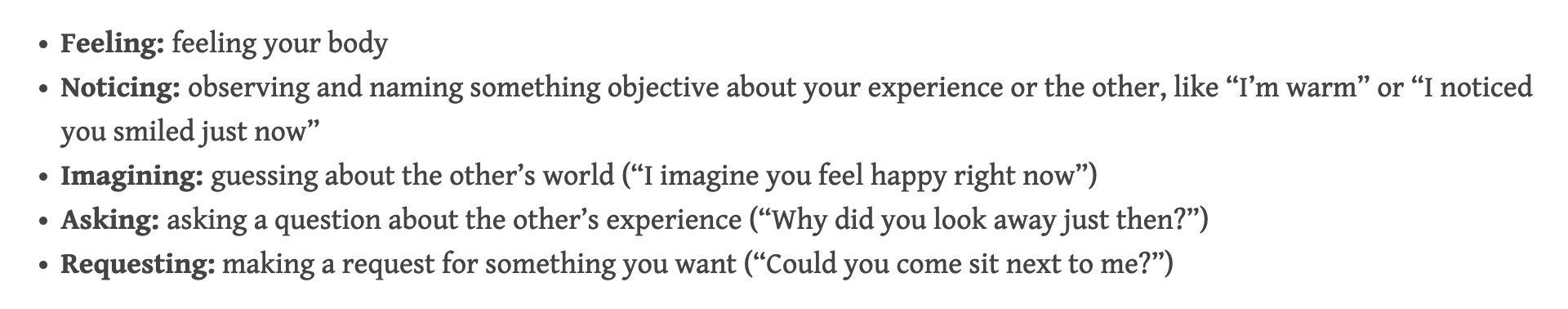

Here are some of the specific moves I learned from Circling:

There are other skills that I learned, which are more nebulous or difficult to describe. But it’s remarkable how often these specific skills—simply sharing what you notice or imagine—can transform a social encounter, whether it’s in a formal circling context or outside of it.

Conclusion

The synthesis of these two influences—my formal education at St. John’s, and the practice of Circling that I was exposed to at the Monastic Academy—are the two biggest influences on how I hold conversations these days, whether formally on my podcast, or in my everyday life.

I follow my curiosity, asking the questions that come to mind—and I am acutely aware of my own experience, and what I notice about my conversational partners. Together, these influences help me to learn about the topics I am interested in, while being increasingly sensitive to my own experience and the dynamics of complex social interactions—building deep connections with fascinating people who I am lucky to have as friends and peers.