I wrote the first draft of this essay in preparation for giving a eulogy at my mother’s memorial service. Her name was Deborah Jane LeBel. I’ve added some of the remarks I made during the service. U can read her obituary here.

At times like these, when someone has passed, or as we look at our own lives and consider our own impending deaths, a question we might ask is, “Am I proud? Am I proud of this life that’s been lived?”

It seems to me that my mother lived a life that she could be proud of. It’s a life that I’m proud of.

I think my mom was happiest when she was grocery shopping, or couponing, or winning one of her contests. She considered frugality to be a virtue and she loved reading The Tightwad Gazette and Refunding Make Cents. In the late 90’s grocery stores still sometimes had double or triple coupon days—where they would double or triple the value of a coupon—she could work magic on those sales days. Whatever she saved or earned or won, she loved to use them for a good cause: a local school or food bank or just someone who she could bring a smile to their face. Her last email to me was about a Dunkin’ Donuts coupon, because she knew I liked to go there for their affordable and quick vegetarian fare.

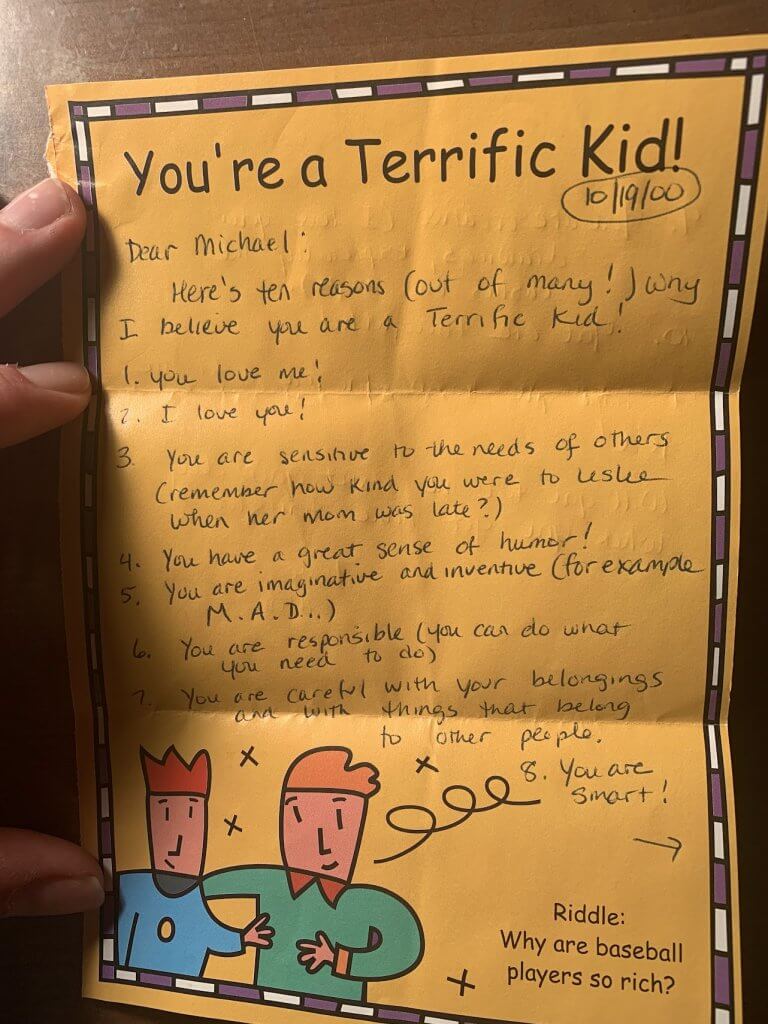

When I was little, Mom wrote me the sweetest notes and put them in my lunch box. She used special little paper for parents to write to their kids that she’d found somewhere, and poured her heart into them.

One of my favorite memories of my Mom is our trip to New York City together. I was obsessed for a time with chess, and New York City is the chess capital of America, if not the world. She planned a trip for us to go to New York City together. We drove to Connecticut, took the Amtrak train into the city, and spent the weekend traveling to different chess book stores around the city, where she bought me more chess books than I could possibly read, and George Washington Square park, where I watched blitz played in person. She wanted to use part of our weekend there to visit her grandmother’s old apartment. I didn’t want to visit it, and was cranky and irritable about it, but we went anyway.

When it was time for me to start looking at colleges, I was overwhelmed by the book I got on schools—some massive index of universities around the world and their statistics. She told me about Loren Pope’s Colleges That Change Lives, which featured her alma mater, Earlham College. She told me I didn’t need to go to Earlham, that I didn’t even need to go to one of the schools in that book, but she wanted me to read it, because it would give me a different perspective on education and what possibilities were available to me.

I ended up applying to what would become my alma mater, St. John’s College. They had rolling admissions with a two week turnaround response, and I was promptly accepted. I didn’t end up applying elsewhere, because it felt like the school for me. It was. I was very happy there, and my education there led me to mysticism, meditation, and later, to my monastic training, to taking the bodhisattva vows, and my pilgrimage and path of service. Her suggestion to read that book changed my life.

I was her only child. I’m sure it won’t surprise you to hear from me that she was an incredible, incredible mother. She went above and beyond. Anything we might reasonably expect from a mother, she did everything she could to help me practically, physically, materially, emotionally, spiritually.

I have no qualms or reservations about her. That’s something that has given me great peace, is a conversation we had several times throughout her diagnosis. I would ask her—I don’t have any grudges or resentments or anything like that, is there anything you’d like to talk about? She didn’t have any. We just loved each other very much.

It seems to me that my mother and I had the same flavor of love, expressing itself through our lives—a similar calling to service, a similar compassion for others, and a hard-working work ethic.

I admired my mom’s work at John Snow Inc. (JSI), where she worked for my entire life until her retirement. I joked that she was JSI’s “project proposal hitwoman”—the person they’d send to close the deal, finish the job when it was time to write proposals for the public health projects JSI worked on.

I would wake up in the morning and she would be poised with her cup of coffee at her laptop, checking her coupon websites and sending work emails. We were both early birds. She loved the sunrise. She would always tell me at the end of the day, when she was tired, that tomorrow would be a new day.

I was grateful that, in the months and years before she passed, we had many conversations about her life, my childhood, and the things we both cared about.

I asked her what her favorite part of working at JSI was. She said she liked working with her boss, Miguel—that he expanded the possibilities in what work she could do at JSI. It was an exciting time in the HIV/AIDS field. Miguel gave her a chance to write things and offer her opinions on what she was working on, to work directly with senior people.

I asked what she was really good at at her job. She said: connecting people, being persistent about getting things done, being committed to the work itself. She didn’t just do the light touch.

She told me and my father a couple of months ago that when she died, she wanted the memorial service to reflect my beliefs, because I believe different things than her and she wanted me to be comforted, too. This touched me so deeply. That’s why we chanted the Heart Sutra in Japanese at her memorial service.

When I think of my mom, the phrase that comes to mind to describe her is as a “quiet bodhisattva.”

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is someone who is dedicated to being of service, who wishes to help all beings. It’s like a Catholic saint, but it’s a voluntary practice, rather than a posthumously awarded title.

Mom didn’t need to talk about her views—she simply demonstrated her love, her kindness, her care.

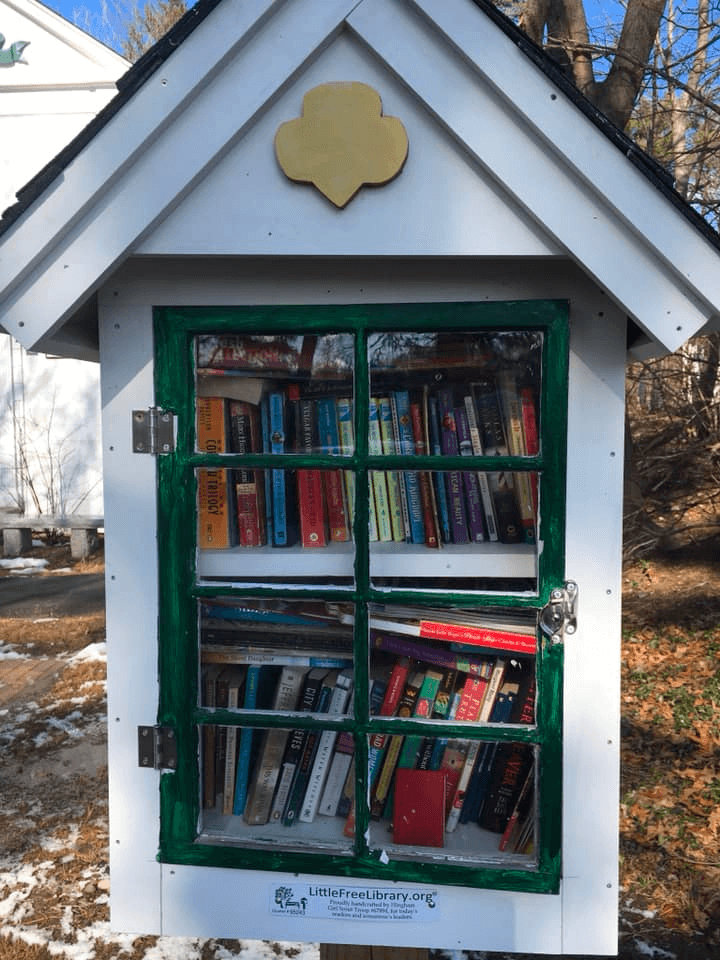

Even outside of her work, Mom was always working on various service projects: donating food to food pantries, collecting toys for children at the holidays, sewing hats and other clothing items for children in winter, donating school supplies to schools, bringing used books to Little Free Libraries around New England.

I asked her why she did her service projects. She said “I see there’s a need. It interests me, and it’s fun. I pick and choose what I want to do. I have the resources to do it. The world needs to be a better place.”

I know she helped people and did service projects that I don’t even know about, that perhaps none of us here know about.

She didn’t care about getting credit, about being seen for the deep goodness that she lived by—she just wanted to help people.

Mom told me once that after she died, she wanted to be in the stars, sending us love. This astonished me. I didn’t know she felt that way. And it strikes me as similar to the imagery I have around sending mettā, loving-kindness—shooting beams of light and love out of my hands.

I learned love from my mother; she was a teacher of love to me.

When I would tell Mom that I loved her, she used to tell me she loved me more. We’d get in fake fights about it. I didn’t like comparing our loves, so I’d let her win.

She told me before she died that she loved me more than I could ever know. I hope she knew that I love her more than she could ever know—although maybe she knows now.

I miss you, Mom. I love you so much. I’ll love you always.

And for those of us that live on, that remember her in our hearts:

dare to love like those who loved you, dare to love like them and even more—it is how you say thanks for what love you received, and pass it on for those to come, who need your love