In 2010, I started a daily meditation practice. I wasn’t looking for deep truths. I was just looking for something that might make me feel happier – less depressed, anxious, and socially awkward, and more at peace with myself and the world.

If you get interested in meditation, like I did, you’ll probably run into Buddhism.

When I started, I wasn’t interested in religion – quite the opposite. I was actively resistant to religion. But over the years, my resistance waned, and my interest in Buddhism increased significantly.

Today, Buddhism is the most significant influence on my spiritual practice. I’ve found it to be extremely useful and pragmatic.

While you don’t have to be a Buddhist to meditate, I strongly encourage dedicated meditation practitioners to earnestly investigate Buddhist teachings with an open mind. The teachings are practical, reasonable, and beneficial.

This post offers a broad overview of Buddhism from my perspective. I’ll start with setting some historical and mythological context for Buddhist practice. Then I’ll dive into specific ways to learn more and implement Buddhist practice in your own life.

The Life of the Buddha

About 2500 years ago, there was a prince named Gotama. He lived from approximately 563 BC to 483 BC. He was a member of the Shakyan clan, a ruling family in the region of northern India where he grew up. His father wanted him to become a king.

As a child, he lived a very privileged life. All his needs were met and he had access to many pleasures and luxuries. He married a beautiful woman, Yaśodharā, and had a child, Rāhula.

Despite all this comfort, Gotama wasn’t happy. He became curious about what life was like outside of his palaces, and asked his servant to take him outside to see the world. On his excursions, he realized people were subject to sickness, aging, and death – something hidden from him until that point. He was filled with grief and despair, knowing that he would one day die.

He became desperate to find another way. Perhaps there was something beyond aging, sickness, and death. Perhaps Awakening, liberation from suffering, was possible. He decided to leave the life of a prince, along with his wife and son, and adopt the life of a wandering religious practitioner or mendicant.

He trained under several teachers, including Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta. While he deepened his concentration tremendously, mastering various concentration states, he didn’t find what he was looking for.

He then decided to become an ascetic, including practices such as extreme fasting and not breathing, to see if he could find an escape through these intense austerities. It was only when he came extremely close to dying that he was forced to acknowledge that punishing his body wasn’t the solution.

He then decided to sit down and practice in meditation until either he died, or found what he was looking for: Awakening, liberation from suffering, an escape from the cycle of birth, aging, sickness, death, and rebirth.

This firm resolution enabled him to Awaken. He then spent the rest of his life teaching others to find what he had discovered for himself. In doing so, he established a community to practice and spread the teachings after his death.

Many of us come to Buddhism because we notice suffering in our own lives. We notice that we are subject to aging, sickness, and death. We notice our own failings, imperfections, addictions, and problems. Naturally, we wish to resolve our suffering. Buddhism claims to offer such a resolution.

The basic claim of Buddhism is that each of us suffers. We are all subject to aging, sickness, and death. Awakening is an escape from suffering, a resolution of suffering. The same Awakening that the Buddha experienced is possible for each of us.

Buddhist Traditions

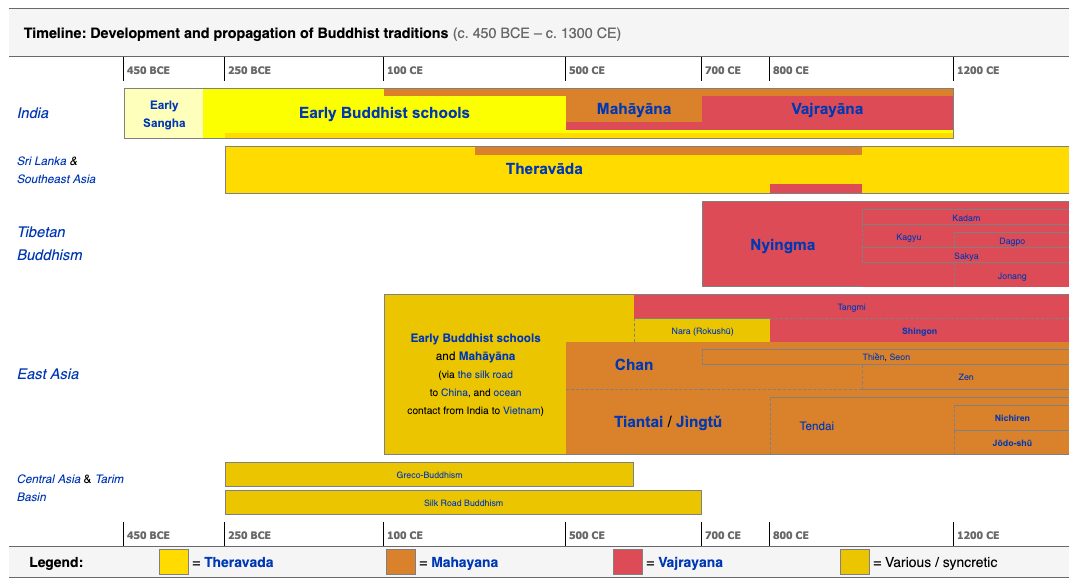

Since the death of the Buddha, Buddhism has spread from Northern India, throughout Asia and the world. Over the centuries, there have been a number of different traditions and schools.

The three main schools of Buddhism are Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna, in chronological order.

Even if you are interested in Mahāyāna or Vajrayāna practice, these traditions are inspired by their predecessors, especially the teachings handed down to us from the Buddha.

Timeline of Buddhism (CC BY-SA, Wikipedia)

Today, I believe there is a need for a new kind of Buddhism, a contemporary Buddhism that meets modern people where they are, and responds to the enormous, unprecedented problems we face. This is what much of our work at MAPLE is about.

Learning Buddhist Teachings

Learning about Buddhism can be intimidating. There’s an enormous amount of material in the Buddhist sutras (scriptures). The Pali Canon, the traditional Buddhist texts in the Theravāda tradition, is approximately eleven times the size of the Christian Bible. And the Theravāda tradition is just one of many branches of Buddhism.

One way to begin learning Buddhist teachings is to learn some of Buddhism’s numbered lists. The Buddha made extensive use of numbered lists as a pedagogical tool. There are many, many numbered lists, like the Five Aggregates or the 37 Aids to Enlightenment. These numbered lists serve as a useful entry point to understanding Buddhist teachings.

Many of the numbered lists are immediately practical in meditation practice or in life. Others help with grasping Buddhism conceptually. Often, they refer to or build on each other. The more numbered lists you understand, the more Buddhist teachings you can understand.

Here are some of the numbered lists that I’ve found most useful in learning about and applying Buddhist teachings, with some context about how I understand them.

The Three Jewels: These are three priceless things – the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha – that we should take refuge in, and base our lives on.

The Buddha refers to the historical Buddha, but also to other Buddhas in other realms, as well as our own capacity for Awakening. The Buddha is an excellent hero but he is not fundamentally different from us—we also can realize the same Awakening that he did.

The Dharma refers to the teachings as taught by the Buddha, which describe the nature of reality itself.

The Sangha refers to the community of practitioners dedicated to practicing the Dharma as taught by the Buddha. These practitioners can be householders or lay people, or they can be monastics (monks or nuns). Friendship and community between the Sangha allows us to deepen our faith, make effort, and find the fruits of the spiritual path for ourselves.

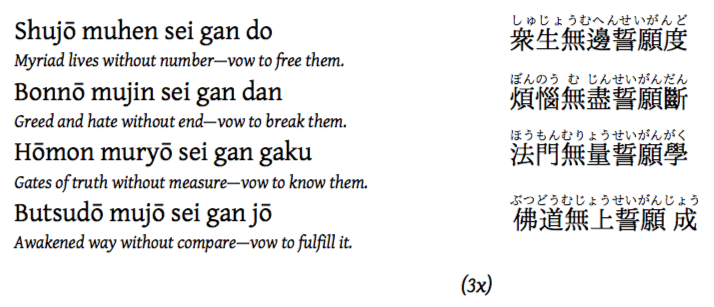

The Four Bodhisattva Vows: This list comes to us from the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, rather than the classical Theravada tradition. Here is how Soryu Forall, my teacher, translates the Four Vows:

These vows are seemingly impossible, and yet we can take up these vows anyway. We vow to save all beings; to end all greed, hatred, and ignorance; to master all paths to truth; and to realize full Buddhahood, for the benefit of all sentient beings. This expresses a deep commitment to service, in this life and any future lives we may have.

The Four Noble Truths: The Buddha said that he taught suffering, and the end of suffering.

The word dukkha is most commonly translated as suffering, but I prefer dissatisfactoriness as a translation, because experiences or phenomena can be pleasant and enjoyable but still ultimately dissatisfactory.

The First Noble Truth is that there is suffering, dissatisfactoriness, dukkha. In our lives, we are subject to aging, sickness, and death. At a moment-to-moment level, there are unpleasant sensations, and even pleasant sensations cannot permanently satisfy us.

The Second Noble Truth is that suffering is caused, that there is a cause of suffering: clinging.

The Third Noble Truth is that there is an end to suffering. Because suffering has a cause, if we remove that cause, the effect – suffering – ends. The end of suffering is Awakening, Nirvana, cessation.

The Fourth Noble Truth is the path from suffering to the end of suffering. This path is the Noble Eightfold Path.

The Noble Eightfold Path: The Noble Eightfold Path takes us from suffering to the end of suffering. Importantly, meditation or mindfulness is just part of the Noble Eightfold Path, and it has six prerequisites. The complete Path includes:

- Right View: seeing things correctly, e.g. that What You Do Matters, that Awakening is possible, and that teachers exist who can help you realize it for yourself

- Right Thought: thinking or intending in accordance with Right View

- Right Speech: speaking in accordance with Right View; speaking in accurate, useful, kind, timely ways with a mind of kindness

- Right Action: acting in accordance with Right View, especially in the way we use and hold our bodies

- Right Livelihood: earning a living in a wholesome way; especially avoiding selling weapons, human beings, meat, intoxicants, and poison.

- Right Effort: exerting effort to prevent unwholesome qualities that have not yet arisen from arising, to abandon unwholesome qualities that have arisen; to give rise to wholesome qualities that have not yet arisen, and to maintain wholesome qualities that have arisen.

- Right Mindfulness: one takes up an object, like mindfulness of breathing or mindfulness of body.

- Right Samadhi: with mindfulness established, one enters samadhi, moving through the jhanas.

The Threefold Training: Spiritual practice, and Buddhism in particular, can be described as three mutually supportive forms of training: virtue, ethics, and morality (śīla), concentration or absorption (samādhi), and wisdom or insight (prajñā). These forms of training have distinct goals and methods but all lead to liberation from suffering and service to others.

The Three Pure Precepts: A broad form of describing beneficial ethical conduct and the spiritual path. Don’t do bad things, do good things, and clarify the mind so that what appears morally unclear becomes clear to you.

The Five Precepts: A more specific form of describing ethical practice. If you take the Five Precepts, you take up the practice of not harming or killing; not stealing or taking what is not given; not committing sexual misconduct; not lying or speaking falsely; and abstaining from the use of intoxicants like alcohol and drugs.

The Five Recollections: These are five subjects or facts that one should frequently remember and consider: that we are subject to aging; that we are subject to illness; that we are subject to death; that everything we love and hold dear will be taken from us; and that we are the owner of our actions (that what we do matters).

The Three Poisons: Our minds have three poisons: greed, hatred, and delusion or ignorance. These things harm us, causing suffering for ourselves and others, and prevent us from Awakening.

The Five Hindrances: When we meditate, five common obstacles can arise: sensual desire (e.g. for food or sex), hatred and ill will (of ourselves or others); sloth and torpor (drowsiness or laziness); worry and anxiety (typically regret about the past or worry about the future); and skeptical doubt.

Each of these Five Hindrances can be overcome through mindfulness, but they also have specific recommended solutions. Sensual desire can be overcome through considering foulness. Ill will can be overcome through generating lovingkindness or compassion. Sloth and torpor can be overcome by generating determination or energy. Worry and anxiety can be overcome by generating calm and relaxation. And skeptical doubt can be overcome through proper attention.

The Three Characteristics: All sense phenomena have three characteristics or marks: impermanence (anicca), dissatisfactoriness (dukkha), and not-self (anatta). All sense phenomena arise and pass away. They cannot permanently satisfy us, even if they are pleasant. And while we have thoughts and images and feelings, those do not constitute a permanent self or soul.

Studying the Buddhist Scriptures

The Buddhist scriptures (sutras) are an excellent way to go deeper into Buddhism. Here are some of sutras that I would recommend if you are starting out learning about Buddhist teachings:

- The Simile of the Mountains (short)

- The Noble Search (medium length, ~30 minute read; story about the Buddha’s path)

- A Safe Bet (medium length, ~30 minute read, dense, describing the path as householders / lay people should see and walk it)

- The Buddha’s Advice to Sigalaka (medium length, ~30 minute read, accessible; recommendations for how householders should live)

Applying The Teachings

When people today get interested in Buddhism, they often begin with meditation. That’s how I began. And while that’s fine, over time, I’ve come to believe that it’s better to start with cultivating ethical behavior, and with learning about Buddhist teachings. Understanding meditation as something that takes place in a larger context of Buddhist practice will help it be fun, exciting, and inspiring – rather than boring and onerous.

The best place to start applying the teachings in our lives is with the first of the Threefold Training, Ethics or Morality (śīla).

To begin with, you can use the Three Pure Precepts to guide you as you make behavioral changes: stop doing bad things, and start doing good things. The Five Pure Precepts can guide you as you decide what harmful things to stop doing: not harming, not stealing, not committing sexual misconduct, not lying or using harsh speech, and not using intoxicants that cloud the mind. Although this might feel overwhelming, you could try it for a limited period – perhaps a month – and see how it impacts your life.

Another important virtue to cultivate is generosity (dāna). This is traditionally considered the chief virtue for householders or lay people to cultivate. While there are many ways to cultivate generosity, the traditional means was to donate to monasteries – to those that are sacrificing their lives, their time and energy, to practicing the Dharma.

Regularly studying the sutras or other forms of teachings will support you as you walk the Buddhist Path. The Sutras share the teachings of the Buddha, but it can also be helpful to receive guidance from contemporary teachers, in the form of talks, books, or in-person interactions.

With ethical behavior established, and a strong foundation in the teachings, you will naturally feel motivated to develop or deepen a meditation and mindfulness practice. Meditation will feel interesting and fun, even when it is challenging or painful. If you’re practicing at home, you might benefit from using a meditation app like Brightmind. Many people find it useful to try to go on a meditation retreat at least once a year. S.N. Goenka’s Vipassana retreats are an excellent, free way to sit your first meditation retreat.

As you deepen in your practice, you may want to find a teacher and a community. Like-minded individuals will inspire you and renew your motivation. Teachers will help you face any challenges that arise, and move forward on the path.

Finally, you might find it useful to formalize your commitments to the spiritual path. Often, Buddhists decide to have a ceremony taking refuge in the Three Jewels. It is also common to take on the Ethical Precepts, whether the list of five shared above or a longer list. In the Mahāyāna tradition, practitioners also often take the Four Great Vows. A formal ceremony might feel inspiring to you, and it might not. It’s not strictly necessary, of course, but it can be motivating, clarifying, and empowering.

Conclusion

Life includes suffering intrinsically. We age, we get sick, and we die – and we watch the people we love go through the same process. There are also many other, different forms of suffering we can experience in our lives, which are more or less common, and some of which are unique to just us.

While human life has always included different forms of suffering, these are especially challenging times. We are currently in the midst of a global pandemic. There is widespread economic inequality, and enormous amounts of depression, anxiety, suicide, addiction, and other social problems. Global warming, species biodiversity loss, and other forms of environmental degradation threaten our climate and life on earth. Many nations have enormous nuclear arsenals, which could be used at any time; meanwhile, new technologies are being developed that could dramatically alter or destroy our civilization and the planet.

Buddhism has always offered a way out of our suffering as individuals, but it is an especially powerful teaching for this specific moment in history. Training in ethics, concentration, and liberative insight can decrease our suffering and increase our fulfillment, making life less fraught and more joyful.

Beyond the benefits it offers us in our own lives, Buddhism may also hold a key to resolving our collective suffering. Addressing our own individual suffering is an important first step towards resolving the problems we face as a civilization and planet.

As our culture and species encounters Buddhist teachings, we may be able to discover a form of Buddhist teachings for our time and culture, which can resolve the complex, unprecedented problems we face.

Further Reading

- Buddha by Karen Armstrong

- The Science of Enlightenment by Shinzen Young

- List of Buddhist Lists by Leigh Brasington

- Buddhism by the Numbers – Lion’s Roar

- Access to Insight

Thank you to Benjamin Pence, Cat Swetel, James Stuber, and Stephen Torrence for reviewing this post, and to Madeleine Charney for editing it.