Right Speech is the third component of Buddhism’s Noble Eightfold Path. Reflecting on Right Speech is a necessary component of the Buddhist spiritual path, but also provides useful guidelines for anyone who is aware of the power of speech to help or harm ourselves and others.

In accordance with Right View, we are aware that speech is powerful. It is an action with consequences—that What We Do Matters. This applies whether we are speaking to ourselves or others, verbally or in writing.

The phrase “Right Speech” or “Noble Speech” sometimes brings up connotations of politically enforced speech and propaganda, e.g. 1984-esque Newspeak and “thoughtcrime.” As a born and bred American, I value Free Speech as much as the next fellow, and have a sense of distaste at being told what I can and cannot say, or how.

However, I’ve found Right Speech to be a useful spiritual practice that I have elected to adopt and practice for myself.

Practicing Right Speech is a voluntary practice. As far as I’m concerned, only you can determine for yourself whether something you say is Right Speech. You can’t determine for someone else whether their speech acts are Right Speech or not.

“And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?”

—Jesus, Matthew 7:3, KJV

You can offer feedback if someone requests it, or there’s a context for it — for example being in the same sangha or community — but as a practical matter, unsolicited feedback on other’s speech acts is unlikely to be well-received or have a positive impact.

The Five Qualities of Right Speech

In the Buddhist canon, there are five qualities of Right Speech (AN 5.198). Right Speech is

- true / accurate

- beneficial / useful

- kind (in words)

- kind (the state of mind from which you say the words)

- timely

Meeting all five of these conditions is necessary for Right Speech.

You don’t need to be a monk, or even a Buddhist, to find these to be useful guidelines for speech.

In general, Western culture already cares about truth and accuracy. Many people, but not all, also often care about whether you use kind words when you speak or write.

However, the other three qualities are generally less emphasized: whether a speech act is beneficial or useful, said with a kind state of mind, or is timely.

Beneficial / Useful: An extreme example of accurate but not beneficial speech would be sharing information about how to create certain weapons that require complex, advanced knowledge to make. That relevant information might be accurate—e.g. atoms or chemicals might work a specific way—but sharing that information could lead to harming others, and could therefore be harmful (the opposite of beneficial or useful).

Kind State of Mind: You can say something that is true, useful, and has kind words—nothing mean in it—but your state of mind might be fundamentally unkind. If you are saying something from an angry state of mind, for example, even the kindest words can sting and be hurtful. Another, more subtle example would be being attached to some kind of idea or preference while you say something.

More broadly, being in a curious, inquisitive, compassionate, kind state of mind is generally useful. It helps to try to see the other person’s perspective, to ensure that you understand what they’re saying and where they’re coming from before you share novel or difficult information with them.

Timely / Context-Aware: Personally, I have found the word “context-aware” to be a better and more useful guide than timeliness. Yes, there is often a right time and a wrong time to say something—but there’s also often a right and wrong context, different mediums that are more or less appropriate.

A few examples:

- As a general rule of thumb, it’s not really appropriate or kind to break up with someone over text message.

- People often prefer to receive negative or constructive feedback in private, rather than in a public setting where they might feel shame or embarrassment.

- If the stakes are high, you might find it easier to say fully, clearly, and calmly what you mean by writing it down.

- Do you understand where someone is coming from? What is their state of mind? What are they wanting or needing? Will they be open to hearing what you have to share, or closed off to it?

Four Kinds of Wrong Speech

In the Samyutta Nikaya (SN 45.8), four kinds of speech are specifically mentioned as wrong speech:

- lying

- divisive speech

- abusive speech

- idle chatter

The Cunda Kammaraputta Sutta (AN 10.176) goes into more detail about each of these qualities:

“And how is one made impure in four ways by verbal action?

There is the case where a certain person engages in false speech. When he has been called to a town meeting, a group meeting, a gathering of his relatives, his guild, or of the royalty [i.e., a royal court proceeding], if he is asked as a witness, ‘Come & tell, good man, what you know’: If he doesn’t know, he says, ‘I know.’ If he does know, he says, ‘I don’t know.’ If he hasn’t seen, he says, ‘I have seen.’ If he has seen, he says, ‘I haven’t seen.’ Thus he consciously tells lies for his own sake, for the sake of another, or for the sake of a certain reward.

He engages in divisive speech. What he has heard here he tells there to break those people apart from these people here. What he has heard there he tells here to break these people apart from those people there. Thus breaking apart those who are united and stirring up strife between those who have broken apart, he loves factionalism, delights in factionalism, enjoys factionalism, speaks things that create factionalism.

He engages in abusive speech. He speaks words that are harsh, cutting, bitter to others, abusive of others, provoking anger and destroying concentration.

He engages in idle chatter. He speaks out of season, speaks what isn’t factual, what isn’t in accordance with the goal, the Dhamma, & the Vinaya, words that are not worth treasuring. This is how one is made impure in four ways by verbal action.

In DN 2, the Buddha also lists a series of topics that are to be avoided by monks and contemplatives. Should they choose to, lay people can also elect to avoid these topics, knowing that they easily give rise to contention and difficulty. The topics are as follows:

“Whereas some brahmans and contemplatives, living off food given in faith, are addicted to talking about lowly topics such as these — talking about kings, robbers, ministers of state; armies, alarms, and battles; food and drink; clothing, furniture, garlands, and scents; relatives; vehicles; villages, towns, cities, the countryside; women and heroes; the gossip of the street and the well; tales of the dead; tales of diversity [philosophical discussions of the past and future], the creation of the world and of the sea, and talk of whether things exist or not — he abstains from talking about lowly topics such as these. This, too, is part of his virtue.”

(DN 2)

Online Speech

People have sometimes asked me how my Twitter account is so consistently wholesome. A big part of it is trying my best to limit what I tweet to stay within these five qualities.

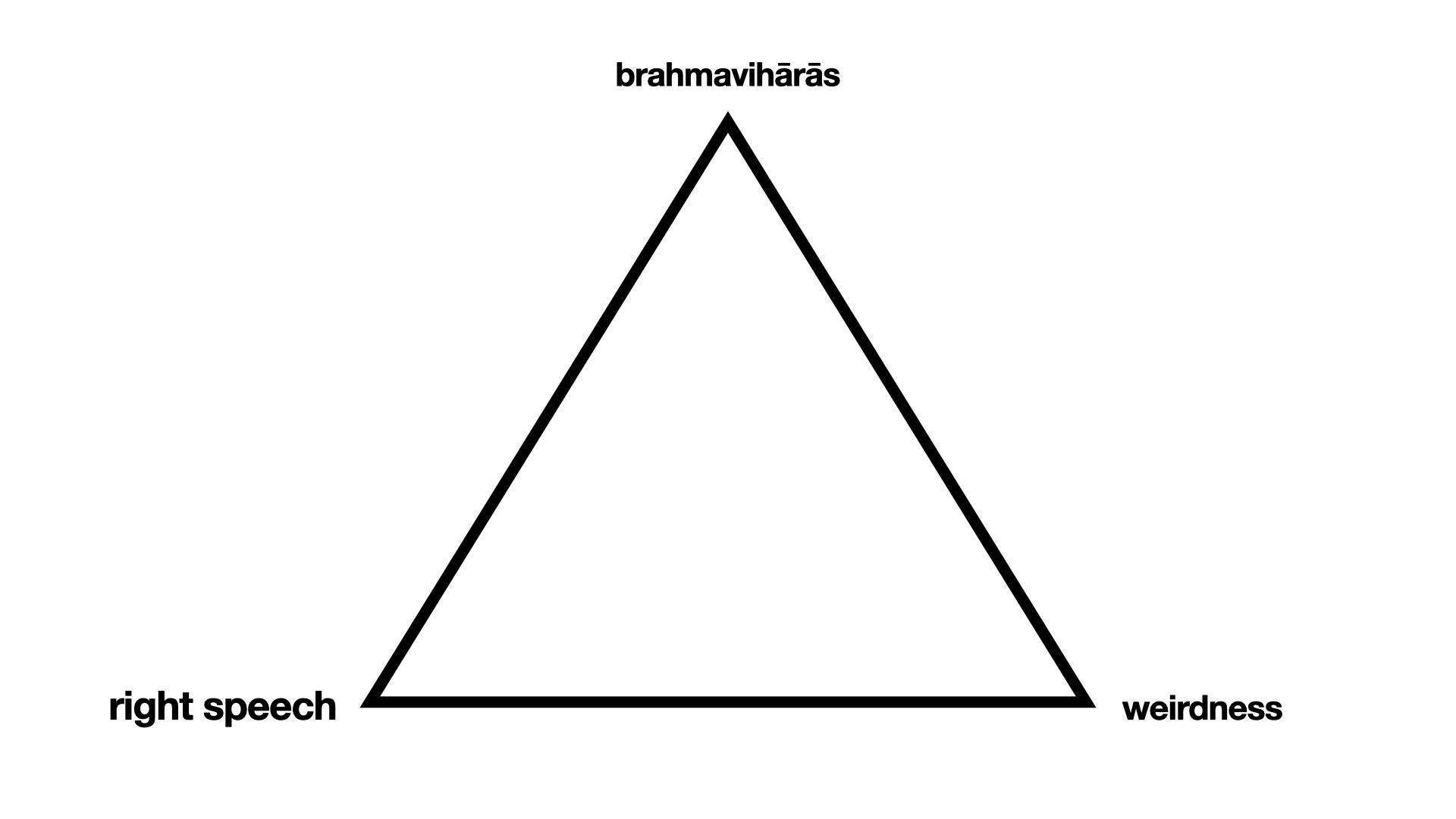

This is surprisingly less constraining than you’d expect. As with all constraints, there is still tremendous room for play, growth, flourishing, authenticity, and yes, weirdness within them.

this account‘s perfect tweet trifecta

I would encourage other Buddhists on social media to memorize, reflect on, practice, and discuss Right Speech, especially the five qualities of Right Speech. Consistently doing so has been tremendously helpful for me in dealing with the power and ethics of online speech acts.

An Exercise to Try

The Buddha recommended reflecting on speech acts before, during, and after speaking (MN 61). As an exercise, take a speech act – something you said recently, or plan to in the future – and check to see if it fits each of those five qualities.

I’ve found that the more times I’ve consciously gone through this exercise, the more I’ve learned about speaking skillfully, and the more my intuitions for Right Speech have been refined.

These are rules of thumb to follow. They won’t necessarily be sufficient for guiding you with more complex or unique speech acts. But it’s helpful to master the basics before you adapt the constraints to your situation.

Further Resources

- Readings on Right Speech from Access to Insight

- Discussing SPEECH on Tiger Time with Taalumot