The rate at which I make Wardley Maps has quadrupled since becoming Assistant Director at the Monastic Academy. They are one of the most useful tools in my strategy toolbox. As Ben Mosior says, Wardley Mapping is the duct tape of strategy tools, “for things you don’t understand but should.”

I can tell you about countless times where Wardley Maps helped me think through a thorny problem, in a variety of contexts. While Wardley Maps are extremely useful to me personally, I have rarely found it useful to share them with others.

If someone is actively interested in them, that’s one thing – those conversations are fun and useful. But I can count on one hand the number of times where I was a) in a work situation where Wardley Maps were relevant and b) explaining Wardley Maps to my colleagues proved to be useful. In fact, I think there was just the one time where the stars and the moon aligned and Sun Tzu deigned to sprinkle mapping blessings into my work life.

As Cat Swetel says, who cares?

Instead, the approach I usually find to be much more useful is to:

- Notice that Wardley Maps are relevant

- Map the relevant situation in my head. Usually, I can do this in about 10-20 seconds.

- If I can’t make a map in my head, or my head starts to hurt, then pull out a whiteboard or the equivalent.

- Say things because of the map I’ve made, without using Wardley/strategy lingo.

Magically, people interface better with the things I say because I mapped them – even if they never see the map, and even if they have no idea what Wardley Mapping is. We can talk around the maps we make, sharing our strategic conclusions without needing to show our work.

There’s a growing awareness in the mapping community that the artifacts aren’t that important – we can throw them away, without losing much. (The phrase “throw them away” isn’t literally about literally throwing them away. I always take pictures of my Wardley Maps. Instead, I understand this as a suggestion to not get stuck on your maps, or think they have to be perfect.) But I would go even further: the tool itself isn’t that important, either.

In psychology, there is a concept called disfluency: “disfluency – the metacognitive experience of difficulty associated with a cognitive task – engenders deeper processing.” (Diemand-Yauman 2011). I learned about disfluency from the book Smarter Faster Better, by Charles Duhigg (notes):

One way to overcome information blindness is to force ourselves to grapple with the data in front of us, to manipulate information by transforming it into a sequence of questions to be answered or choices to be made. This is sometimes referred to as “creating disfluency” because it relies on doing a little bit of work: Instead of simply choosing the house wine, you have to ask yourself a series of questions (White or red? Expensive or cheap?). Instead of sticking all the 401(k) brochures into a drawer, you have to contrast the plans’ various benefits and make a choice. It might seem like a small effort at the time, but those tiny bits of labor are critical to avoiding information blindness. The process of creating disfluency can be as minor as forcing ourselves to compare a few pages on a menu, or as big as building a spreadsheet to calculate 401(k) payouts. But regardless of the intensity of the effort, the underlying cognitive activity is the same: We are taking a mass of information and forcing it through a procedure that makes it easier to digest.

“The important step seems to be performing some kind of operation,” said Adam Alter, a professor at NYU who has studied disfluency. “If you make people use a new word in a sentence, they’ll remember it longer. If you make them write down a sentence with the word, they’ll start using it in conversations.” When Alter conducts experiments, he sometimes gives people instructions in a hard-to-read font because, as they struggle to make out the words, they read the text more carefully. “The initial difficulty in processing the text leads you to think more deeply about what you’re reading, so you spend more time and energy making sense of it,” he said. When you ask yourself a few questions about wine, or compare the fees on various 401(k) plans, the data becomes less monolithic and more like a series of decisions. When information is made disfluent, we learn more.

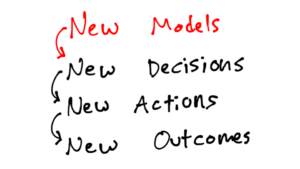

When I first started learning about strategy, I thought I needed to learn all the tools, and use them perfectly, so that I could make correct decisions.

Then I realized that correct decisions are a mirage – there are no correct decisions, only choices that make good consequences more or less likely.

Later, I learned that the artifact doesn’t matter – you can make “incorrect” maps and throw them away.

But learning about disfluency has completely taken the pressure off of learning strategy “correctly.” Which tool you use and how you use it is much less important than making the available information disfluent, forcing us to look at what’s in front of us in a new way.

Take Wardley Mapping. I know the maps look intimidating at first, but you can’t really do it wrong. The tool is less important than the fact that the process forces us to rethink what’s in front of us.

This means that you can wildly misapply tools and still learn something. For example, you could try using an implementation tree or a Wardley Map or a 2×2 without even knowing if it’s “the right tool for the job.” It might even be that you’re using the tool for something that it isn’t suited for, without knowing that. Even so, you’ll still see things anew, and therefore make new decisions.

Duhigg continues:

When we encounter new information and want to learn from it, we should force ourselves to do something with the data. It’s not enough for your bathroom scale to send daily updates to an app on your phone. If you want to lose weight, force yourself to plot those measurements on graph paper and you’ll be more likely to choose a salad over a hamburger at lunch. If you read a book filled with new ideas, force yourself to put it down and explain the concepts to someone sitting next to you and you’ll be more likely to apply them in your life. When you find a new piece of information, force yourself to engage with it, to use it in an experiment or describe it to a friend—and then you will start building the mental folders that are at the core of learning.

So do go ahead and Learn Wardley Mapping. Grab a paper napkin, make a map, profit, toss your napkin away and Wardley Mapping too!

Subscribe to my newsletter, my YouTube channel, or follow me on Twitter to get updates on my new blog posts and current projects. You can also support my work and writing on Patreon.