I’ve been curious about the mental models community for some time. I like what they do, and have learned from watching from afar. But I never felt quite at home.

People who lionize mental models are often concerned with domains like finance, investing, and better business decisions. I’m not very interested in all of that. I don’t want to make more money for myself; I don’t care about a traditional career path. I’m concerned about the planet. Monastic training seems like the best thing I can do to help with the enormous problems we face. I want to deepen my meditation practice, grow as a leader, and serve others more broadly and more deeply.

To steal something I saw Peter Limberg do recently (following Rival Voices before him): I vibe with the mental models community’s insistence that ideas be useful for our lives. I do not vibe with what I perceive to be a myopic interest in career grinding, better business decisions or investment decisions for the sake of profit, and general economics/tech/start-up fanboy-ism.

Unfortunately, this vibe mis-match has led me to ignore some of the content from this community for too long. I haven’t read Munger in the original, or Peter Bevelin’s Seeking Wisdom. I subscribed to the Farnam Street community for a year and let my subscription expire.

In recent years, though, a few things I’ve read have given me the chance to revisit my whole conception of mental models. Along the way, I’ve realized that mental models are useful in domains beyond finance and business – even in meditation, monastic life, and spirituality more broadly.

In this post, I will give an account of what mental models are. I’ll also share how I’ve applied these ideas in my own life, and how you might begin to do something similar. I hope this post will give you a more accurate and useful understanding of what mental models are all about.

The Use and Abuse of the Term ‘Mental Models’

Cedric Chin of the Commonplace blog has done extensive work in recent years arguing against and refining the way mental models are discussed and used in the mental models community. Much of my thinking here is due to Cedric’s prior work.

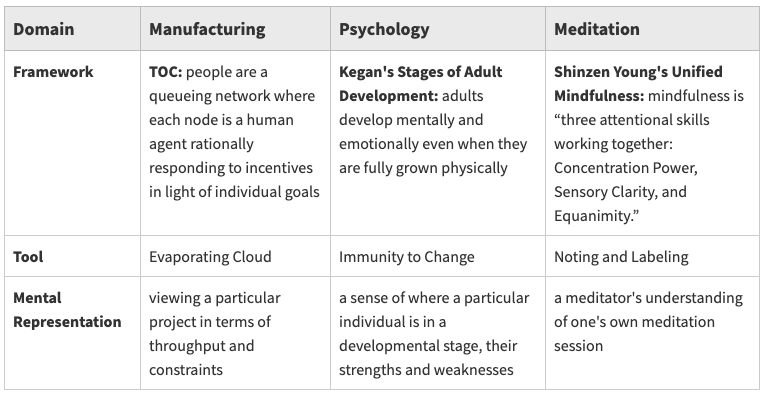

Cedric claims that the term mental model has become a “catch-all phrase to lump three different categories of ideas together”:

- Frameworks: frameworks for decision making and for life.

- Thinking tools: specific techniques for thinking, often drawn from a wide variety of domains like behavioral economics, philosophy, and finance. They are often most relevant to and best applied in the domain from which they originate, but can be applied outside of that domain, with consideration and care.

- Mental representations: the internal representations that we have of some problem domain; the story in your head about the dynamics of an unfolding situation, which is implicit, private, and fully concrete. This may involve pattern matching intuition to past experience. These are difficult to communicate explicitly because they are tacit knowledge, or ‘technê.’

Here are some examples:

Specific frameworks and thinking tools are extremely useful, and worth learning. But my sense is that specific concepts are overrated in the mental models community, and the skill of developing and honing mental representations is underrated. This is related to what Cedric calls the Mental Model Fallacy.

This post is largely concerned with the third use of the term, the skill of developing mental representations and tacit knowledge for orientation and problem-solving. For the remainder of this post, the phrase “mental models” refers to developing mental representations in Cedric Chin’s terminology, unless otherwise specified.

The Psychology of Mental Representations

What exactly is this skill of mental representations, and how do we learn it? This is the question Charles Duhigg investigates in his book, Smarter, Faster, Better. I’ll summarize the relevant portions of his book here.

Duhigg reviews psychological research demonstrating that the skill of creating mental models helps in a variety of different environments. This skill has been proven to help you manage your attention, and stay calm in chaotic environments. It also leads to improved results, such as better grades or higher earnings.

As a way to explain what mental models are, Duhigg relates the story of Darlene, a nurse working in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Darlene was making her normal rounds on her shift, when she saw a baby that made her worried. The machines monitoring the infant weren’t reporting anything problematic, and the RN watching the baby didn’t see anything wrong, either. But Darlene did.

She noticed that the baby’s skin was mottled, not pink; the belly was distended, and a recent blood draw showed “a blot of crimson, rather than a small dot.” Any one of these things would have been fine or normal, but all of these things together caused Darlene to be concerned about the health of that baby.

Darlene pulled the attending physician aside and insisted they give the baby intravenous antibiotics. The doctor trusted Darlene’s intuition, and ordered the medication as well as further testing. Those tests came back showing “that the baby was in the early stages of sepsis, a potentially fatal whole-body inflammation caused by a severe infection. The condition was moving so fast that, had they waited any longer, the newborn likely would have died. Instead, she recovered fully.”

Darlene saved the baby’s life. How did she do it? The other nurse on duty had the same baby in front of her, and the same information available. But neither that nurse nor the machines monitoring the baby had noticed a problem. Darlene did.

When asked for an explanation by researchers, Darlene said that “she carried around a picture in her mind of what a healthy baby ought to look like- and the infant in the crib, when she glanced at her, hadn’t matched that image.”

In other words, Darlene had a mental model of what a healthy baby looked like. That model allowed her to notice anomalies in the baby’s appearance that monitoring machines and the other nurse didn’t.

People who use mental models to manage their attention “share certain characteristics”:

- they “create pictures in their mind of what they see”

- they “tell themselves stories about what’s going on as it occurs,” “[narrating] their own experience within their heads”

- they tend to “answer questions with anecdotes rather than simple responses”

- their daydreams are usually imaginations about future conversations

- they visualize their days ahead with a high degree of detail and specificity

- when life doesn’t match their mental model, they become curious and interested

From this perspective, developing mental models is essentially a tendency towards narrative thinking. This looks like telling stories – lots of stories – about what’s happening as a way to reach deeper understanding.

Mental Models are Broadly Useful

Duhigg’s examples, drawn from the medical and aviation industries, show how mental models are a broadly applicable human skill, that can be useful in many domains – not just finance or business.

You won’t find Darlene’s mental model of a healthy baby in a list of top mental models. Reading someone else’s list won’t help you replicate their success. Instead, you’ll need to learn to make your own mental models, based on your own knowledge and first-hand experience in the domain you want to succeed at. Only with your own direct experience and skill can you make use of others’ best practices and models.

I’ve never been very concerned with making money. But since I read Duhigg’s book, I realized that mental models were useful for me, in my life. I have used mental models extensively in my exploration of domains like productivity and strategy. But mental models have also been useful in other aspects of my life – aspects that are unrelated to making money or worldly success.

Application to Phenomenological Domains

While mental models are demonstrably useful in “practical” fields like finance or investing, I would argue that they are also useful in what we might call “phenomenological” domains, like spirituality, meditation, and circling.

This may not at all be obvious to you. It wasn’t obvious to me.

Thinking back on it, that non-obvious connection seems to be because spiritual communities often give off the vibe that thinking is bad. This is a subtle point, because not thinking is indeed a useful skill in meditation and similar practices, especially during intensive practice periods or for monastics and contemplatives dedicating their life to meditation practice.

However, it’s not that thinking is bad. It’s that it’s useful to be able to not think, and then to be able to decide whether to think, or not, in a given situation. It’s useful to not think when you’re on a meditation retreat. It’s useful to think when you’re in a meeting, or writing a blog post. It’s useful to think about how to sustain a community – what the mission should be, how to organize the community, how to raise funds, etc. And it’s even useful to think about meditation and spiritual practice, in a meta, reflective way – just not always while you’re doing it.

Here are some ways that I’ve used mental models in these domains:

- Meditation: digesting different frameworks and techniques for meditation; developing mental representations of my own progress and obstacles

- Meditation Instruction: developing my own mental frameworks around meditation progress; assessing student progress and responding accordingly

- Monastic Training: develop mental representations of the monastic training structure, its intentions, and individual + group dynamics

- Circling: maintaining a read/interpretation of what’s happening in a circle; asking others about whether my reads are accurate; refining my frameworks and thinking tools based on that feedback.

Much of the content on this blog is the result of my own wrestling with applying mental frameworks and tools to developing mental representations relating to these domains.

Make Your Own Damn Mental Models

Most of the discourse around mental models surrounds specific frameworks or techniques that are explicit, public, and abstracted from particular situations – such as feedback loops or compounding. However useful these concepts are, simply memorizing or applying concepts with proven utility isn’t what psychological researchers are describing.

Making mental models is an activity. This activity is telling yourself stories about stories about what’s happening, in situations that matter to you.

Your stories, your mental models, may very well involve specific concepts from other contexts. However, doing so effectively may require you to modify the concepts, combine them with other concepts, or develop your own new concepts.

It will certainly require you to use narrative thinking to connect all of the relevant concepts. Only then will you have a useful and relevant story about what’s happening in a specific situation that you care about.

Duhigg suggests that we “[develop] a habit of telling ourselves stories about what’s going on around us.” “If you want to make yourself more sensitive to the small details in your work,” Duhigg says, “cultivate a habit of imagining, as specifically as possible what you expect to see and do” at work, so you can “notice the tiny ways in which real life deviates from the narrative inside your head.”

Here’s a simple example. We might know that we have a meeting later in the day. Perhaps we have reason to think this meeting will require some care and skill, because there will be complicated topics of discussion, or because the decisions made will have significant impacts on people personally.

Before the meeting, we can envision what we think is likely to happen during the meeting. We can tell ourselves stories about the specific challenges or situations that might arise. What are the other people like? What are they motivated by? How will they respond? How do we want to respond in turn? During the meeting, we can make decisions and act based on our refined orientation towards what’s happening. Finally, after the meeting, we can look back and reflect on the ways that the meeting didn’t match what we expected – an activity that further refines our mental frameworks, tools, and representations.

When we have enough skill in making mental representations, and employing frameworks and tools, we can create a virtuous feedback loop between the frameworks and tools we have and use, and our mental representations of different situations. As we employ those tools in a specific situation, noticing where they work and don’t, we can develop new frameworks and tools that better reflect the situations we’ve found ourselves in.

You can develop the skill of constructing mental models, simply by developing the habit of telling yourself and others stories about what’s happening in your everyday life and why.

Resources

- Smarter, Faster, Better by Charles Duhigg (notes)

- The Mental Model FAQ (Commoncog)

- Monastic Strategy (tasshin.com)

Thank you to James Stuber and David Howell for providing feedback on drafts of this post, and to Cedric Chin for his prior work and for answering my clarifying questions.