During my time training at the Monastic Academy, I’ve been on two pilgrimages. The first was in Vermont, in the summer of 2015; the second was in California, four years later, in March of 2019.

Pilgrimage has come to be a very important spiritual practice for me, one that complements my meditation practice and brings me great joy. I treasure the opportunity and privilege to go on pilgrimage.

This post will describe the practice of pilgrimage, both because I believe you will find it interesting and perhaps some of you will be inspired to go on a pilgrimage of your own some day.

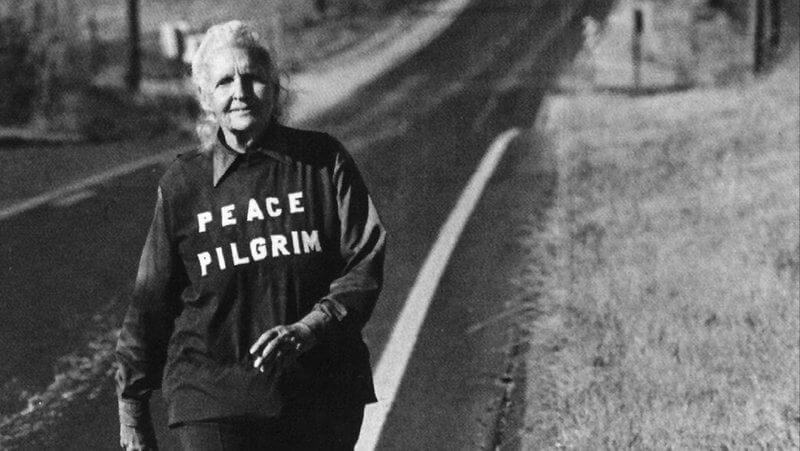

I learned about the practice of pilgrimage from my teacher, Soryu Forall, and from reading Peace Pilgrim, who Forall often talks about. Peace Pilgrim was an American spiritual teacher in the last century, who spent the last several decades of her life on foot, walking for peace – world peace, peace amongst groups, peace between individuals, and also inner peace. I wrote about her life and teachings here.

For many people and traditions, the practice of pilgrimage means going to a particular place or holy site, perhaps to Jerusalem or Mecca or walking El Camino de Santiago. In the way that I practice pilgrimage, as inspired by Forall and Peace, you don’t walk a particular route or go to a particular place. You can practice a pilgrimage anywhere (within reason).

A pilgrimage is a chance to practice trusting.

You start at some place, any old place, and start walking. You come to a fork in the road.

Do you go left, or right? You don’t have a plan for where to go – that’s the only rule. So how do you decide which way to go? You trust.

Trust is the opposite of planning. Trust is the opposite of rushing. Trust is the opposite of hesitating.

Somehow, you just have to make a decision. You do that by trusting.

The decision whether to go left or right is the classic, most basic opportunity for learning the skill of trust. But trusting goes much deeper than that.

You meet someone, and you feel inclined to talk to them. Trust that.

You meet someone else, and you notice you don’t want to talk to them. Is your instinct saying this person is dangerous? Or, are you rushing, avoiding the present moment? Somehow, you have to decide. Somehow, you have to trust.

Trust is about our most basic, primal level of existing and relating. On pilgrimage, without a plan, without a destination, you have to trust that there will be a place to sleep, that there will be food to eat.

On pilgrimage, you are homeless, without a roof over your head. You have to trust that it won’t rain, or that there will be shelter, or that the rain is for the best somehow anyway.

On that primal level, deep fears will come up. Fears for your life. In the face of fear, you have to trust that you won’t die, whether from natural causes or otherwise. You have to trust, against all society’s conditioning, that you won’t get robbed or murdered. You have to find trust that people are basically good.

Trust is the belief that this is the perfect experience. This is the perfect experience to be having, whatever it is.

This kind of trust isn’t contrary to common sense. It’s not permission to be stupid. It’s more fundamental than that.

Here’s a practical way you have to trust: you want to carry as little as possible, because you have to carry it all yourself. If you carry too much, if you’re too attached to your possessions, your back, legs, and feet will give you that feedback soon enough, and you’ll learn.

Peace carried very, very little: reportedly she had only a pen, a comb, a toothbrush, and a map. I have not reached that level of trust.

On my first pilgrimage, I carried a bag with clothes, toiletries, a sleeping bag, mat, and that was about it. On my most recent pilgrimage, in California, the sleeping bag and mat that I had handy wouldn’t fit in my backpack, so I just used the tarp. That decision was a bit extreme on the trust spectrum. I can’t say I’d recommend it. It was really cold. Towards the end of my trip, someone gave me a sleeping bag that is more portable than the one I was using at the monastery – and that kept me a little bit warmer at night.

A pilgrimage is, above all, an adventure. A quest. A journey. There’s nothing like breaking routine, scene and setting to insert spice into life.

Let me tell you my favorite story from going on pilgrimage.

I started my second pilgrimage, in San Mateo, California. I’d been dropped off by the teacher at our California location, Jōshin, on a random street. I don’t know how he picked it. I suppose he trusted. He gave me a very nice hug and said, “Have fun.”

There I was, standing there, with just my backpack with my tarp and some clothes, and no place to go, no plans for a bed to sleep in that night. It was evening, and it was getting cold. So I started walking – to the right.

Very shortly thereafter, I found a church. I ambled onto the property, and sort of hung out there for a little bit. You could say I was loitering.

There were some people practicing music for the next service, and it was really beautiful.

I walked around the property, and happened to find the pastor, who happened to be there, even though it was late evening on a weekday. He was an older man, and I imagined he was happy to see me, a young man, wandering around his church. I imagined he thought to himself, “Oh! there’s a young person here! Maybe he’ll be interested in Christianity!”

We had a nice chat, and soon enough I was trying to explain to him what I was doing, both on pilgrimage and with my life. I got the sense that he was impressed by my dedication, but concerned that I was dedicating myself to the wrong religious tradition. Then we debated whether I was a Christian or not. That was interesting.

At this point, I decided to trust. He was a Christian. Why not ask him for a place to stay? “Can I stay at this church tonight?,” I asked.

“No, no, no, unfortunately not,” he said.

So that was interesting. I can’t say I expected differently, but it was interesting from my perspective.

So, I trusted his rejection. I trusted. I wasn’t going to be staying there that night. It was starting to get dark out, and we had been talking already for some time, so I decided to get on my way. I started walking again, looking for a place to spend the night.

Eventually, I found a quite nice spot by an elementary school in San Mateo. There was a big property with a baseball field and all kinds of buildings. On the edge of the school, there were lots of bushes. That was useful because no one was going to see me if I slept in them. I didn’t want to get arrested or scare anyone. So, I snuck in the bushes with my bag, and my tarp and rolled up in it, and tried to sleep. I wasn’t very successful because, as you can imagine, it was getting quite cold, and all I had was a tarp, and it turned out I didn’t have very warm clothes packed, either. But there I was, and it wasn’t comfortable at all.

Suddenly, I didn’t want to be there at all. A pilgrimage had seemed like such a good idea, but once I was settled in, and rolled up in that tarp, at an incline, hidden under some bushes on the edge of a property of an elementary school, I really didn’t want to be there at all.

I had my phone with me, and it would have been easy to turn it on and call Jōshin. I could just say, “Jōshin, please come get me. I’m rolled up in a tarp and I’m cold and this was a terrible idea. I’m so sorry, sorry for wasting your time, friend, and making you drive out to San Mateo again – but can you please come get me?”

But I didn’t do that. I trusted that this was the experience that I should be having.

When I decided firmly that I wasn’t going to call Jōshin, the experience shifted. It shifted into a kind of purification experience. It was still cold, and dark, and very uncomfortable; I couldn’t sleep; I felt increasingly guilty about hiding in the bushes. There were strong emotions coming up in my body, but I just sat there, quite still, and felt them. I still didn’t want to be there, but I accepted that. I accepted all of it.

Because I was accepting the discomfort, it started to become quite pleasant, which is why I described it as purifying. It wasn’t that it became comfortable, or that I suddenly wanted to be there. It was just that by accepting it, it was suddenly quite pleasant in addition to all of the discomfort. That experience, which in meditation we call equanimity, helped me to fall asleep, just a little bit.

But then, at about 1:30 AM that night, it started raining a little bit. Since I just had a tarp, I knew I was at risk of getting soaked.

When you sleep outside at night without a tent or roof over your head, you fall asleep aware that it might start raining in the middle of the night. So you prepare for that, and are ready to jump up quickly from your sleep if need be, and find shelter.

There were some awnings at the school, but they were quite brightly lit, so it was not discreet. Also, the surfaces were concrete; the floor would actually have been even worse than being at an angle in a bush, because it was bright and extremely uncomfortable. So I trusted all of that as a clear signal that the school was not the place for me to sleep.

So I kept walking, and then I found what ended up to be the perfect abode for the remainder of my evening. I was so excited, because it was very clear to me that I had found the perfect place for me to be asleep.

My whole body was telling me, “This is it! I’m gonna trust it to be perfect! At last, thank God, shelter! Yes – a Porta-Potty!”

That’s right. I spent the rest of the night in a Porta-Potty.

And it was perfect. It was the perfect experience. It was really raining at that point, and it was dark out, and all I had was a tarp. But then I found the Porta-Potty. In urban California, wherever you are, in every neighborhood there’s going to be a Porta-Potty, because someone’s doing construction, and those construction workers will need a bathroom. So that was that. The construction workers had their bathroom by day, and that night, at least, I’d found my shelter. Not a church; not a school; a Porta-Potty.

I went inside, and actually miraculously it was the cleanest Porta-Potty I’ve ever seen. It actually had a calendar of when it had been cleaned, and it said that they cleaned it every week, and miraculously, it had been cleaned that morning.

It was actually spotless – perfect, not the association of a Porta-Potty that just came to mind for you a few paragraphs ago. It was the perfect Porta-Potty. Pristine. Brand new, almost.

At first, I tried to sit on the toilet, with my back upright against the back of the Porta-Potty, but then I realized that wasn’t really going to work. So I sort of laid down, as best I could on the floor, all 5’11” of my body squished into a modified boat pose, and slept at the base of the Porta-Potty. I actually got very restful sleep for about four hours.

At around six in the morning, a runner came by the Porta-Potty with their dog; and the dog, I think, smelled me. It barked, saying, “there’s something unusual about this toilet.” That was my sign, my chance to trust, that it was time for me to go.

This, of course, makes for a great story: the Night I Slept in a Porta-Potty. But it also illustrates very clearly what I mean by trust. I trusted when I couldn’t stay at the church. I trusted that I should sleep at the school for a time, and then leave when it began raining. And I trusted when I found the unlikeliest of shelters.

It’s relatively easy, at least for me, to practice trusting on pilgrimage, because you’re constantly faced with opportunities to trust. You need to trust at every intersection, when you have to decide whether to go left or right, forwards or backwards. There is a chance to trust every time you’re afraid that there won’t be food for you, and every time it gets dark out, when you’re worried about where you’ll stay that night. While this skill of trusting is relatively easy to cultivate on pilgrimage, it’s useful in other areas of life.

After I went on my first pilgrimage, I realized that the same skill of trusting is useful in meditation as well. Somehow it had been difficult for me to notice that before. I think it’s something about practicing meditation inside, which is how I usually meditate, or about staying still. It’s not that you can’t trust in those circumstances, it’s just hard to notice that trusting is an option.

Now, when I sit down to meditate, I can trust that no effort is wasted; I trust that I don’t need to know how to meditate, that I can discover for myself which direction to go in. Somehow, I can learn how to meditate with my body, even if I don’t cognitively know or understand what I’m doing.

Practicing trust on pilgrimage leads to other changes, too. It leads to an acceptance of circumstances in daily life. Shortly after I returned from my pilgrimage in California, I received a phone call from our location in Vermont, asking me to return to the East Coast to assume a leadership role there. “Will you do it?”, they asked – “and can you move soon, perhaps as soon as a few weeks from now?” There was only one thing to do: trust. I just trusted. This move, so sudden, was just what was needed at that time.

It didn’t matter that it was the second time I’d be moving across the country in less than a year. It didn’t matter that it was yet another dramatic shift in my life. Because I had practiced on pilgrimage, I simply accepted it fully, trusting the flow of life, from place to place, role to role, situation to situation. Not trusting was harder than trusting; trusting was more joyful than resisting.

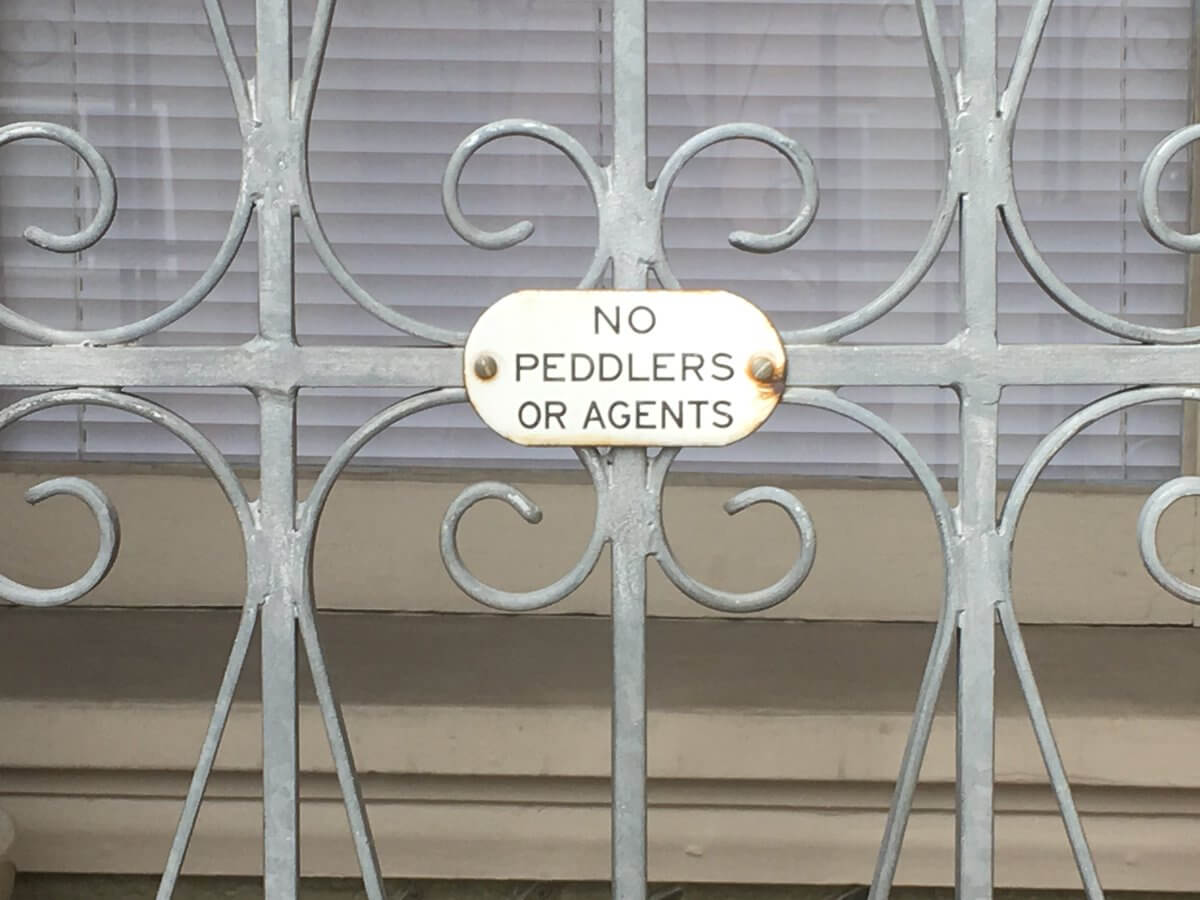

On my most recent pilgrimage, it became very obvious that there isn’t much understanding of pilgrimage in our country. People aren’t very… trusting of strangers.

If I was completely trusting, by my own standards, I wouldn’t bring or buy food. I would trust that others would provide. But on both pilgrimages I’ve gone on, I’ve purchased most of my food. Sometimes people have let me stay with them or on their property, but receiving food seemed like a long-shot.

In my assessment, it’s not reasonable to expect that the average American I haven’t met before will offer or give me, a pilgrim, a wanderer, food or shelter. Some people will, of course. People have done that for me. But the default is that they won’t.

The exception is that if I see someone I already know, who already trusts me, they are always quite generous. Arguably, their generosity proves the rule, but I’m very grateful for it anyway.

Cultures older or less fortunate than our own have been quite clear about the importance of caring for strangers, wanderers, and the less fortunate. We have work to do, America.

When my last pilgrimage ended, it ended somewhat abruptly. There wasn’t a clear conclusion, moral, or lesson. It reminds me of a novel I read once: an adventure story, which was an exciting read but didn’t completely make sense or have a strong conclusion.

In that story, and on pilgrimage, exciting things keep happening and you don’t know why or where it’s going. All you can do is simply enjoy the show. Somehow, for reasons you know not, it’s the perfect experience for you to be having.

Thank you to Nathan Hechtman for helping me to create the first draft of this post, and to Saddhasīla Wolf for helping me to edit it. Thank you as well to the Monastic Academy and OAK for supporting the two pilgrimages I have been fortunate enough to go on.