This post shares my perspective on The Godfather films and novels, and how they have influenced me personally. It includes spoilers.

The Godfather films—The Godfather and The Godfather II—are widely considered some of the best films of all time. They are some of my favorite films, and have been extremely important to me.

Of course, they are enjoyable stories to watch or read. And, as an author of fiction, who learns from others’ stories, I admire and learn from the craft of storytelling as demonstrated by Puzo and Coppola.

But the Godfather stories have also been spiritually important to me. This may seem like a strange thing to say, given that they are about the Mafia, about theft, drugs, murder, conspiracy, and betrayal—about infidelity, violence, abuse, corruption, rape, drugs, gambling, booze, prostitution, and racism.

To me, The Godfather films are not merely dramas about a crime family. They are about America, about family, about virtue and vice, about excellent leadership and unforced errors, about karma and its consequences. Watching the movies and reading the novels has served as an imaginal inspiration and a practical education.

Two Leaders, Father and Son

To me, The Godfather Parts One and Two show two leaders, their rise and fall: Vito Corleone, and his son, Michael Corleone.

Vito Corleone is, to my mind, an excellent leader. He cares about his family, his people. He thinks first and foremost of them, is motivated by their care and protection, his desire to see them succeed. He is not susceptible to the same petty vices that we see other characters prone to.

Michael Corleone is, at times, commendable and inspiring. I admire the devoted love and clever intelligence with which he protects his father in the hospital; the creativity with which he finds a solution to Sollozzo’s treachery; and the earnest, valiant attempts he makes to fill the shoes his father left him. I recognize his loyalty to his parents, his siblings, and his children. But he is also motivated by guilt, jealousy, anger, and hatred—vices which fill his mind, and manifest in his actions, and ultimately his moral downfall.

Although he is clever and strategic, he is not excellent. We see him make major strategic and relational errors. I think his father would be proud of certain actions he took as a leader, and of his earnest attempts. But I suspect his father would disapprove of many of his actions, both as a leader and as a husband to Kay, a father to his children—a brother to Fredo (who he orders killed) and Connie (who he discounts and mistreats).

To my mind, Michael Corleone’s decline in virtue (albeit rise in power) began when his first wife, Apollonia, was murdered.

One’s choice of partner matters quite a bit—not only for one’s own happiness, but for the fate of your family. Vito married well, and that suited him, and the Corleone family. We see Vito’s wife as a quiet but excellent mother and wife (albeit enmeshed in a patriarchy, and its problems).

Michael and Apollonia were an excellent match, and they were truly happy together for the brief time they were courting and wed. I think Michael would have done much better in his life, in his work, for the family, if Apollonia hadn’t been killed. I think he would have been a more optimistic, kind, considerate man, like his father.

If Michael was catalyzed into joining his family’s business by the attacks on his father, he was radicalized by the murder of his first wife. All bets were off, then. He became a darker man, a more jaded man—and, importantly, one who felt compelled to return to Kay, his former love.

Kay was a good match for an innocent Michael, the war hero Michael, the “good college boy” Michael— one who had not joined the ranks of the Corleone family—but a poor match for a Michael who had murdered for his family, who would ultimately take power within it. Perhaps their marriage was fated, but it was ill-matched, and they both suffer for it—as does their family, both the nuclear family with their children, and the larger Corleone family.

Importantly, paradoxically, this means that Michael’s decline in virtue didn’t begin with the Sollozzo-McCluskey murders. Yes, he killed—an action that is reprehensible in most religions, and certainly Buddhism. But within the universe, this action has a kind of logic to it, and is somehow morally defensible. Michael kills not to murder for its own sake, out of cold blood, but to defend his father, to defend his family.

For similar reasons, within the context of the Godfather stories and world, I don’t make special judgments of his murder of Carlo (Connie’s abusive husband), or even, perhaps, the hits he orders during his Godson’s baptism. They are in character, and have a kind of regrettable necessity to them. We see that, for Michael, a leader is someone who must make hard choices, who must hold heavy burdens privately within his own heart.

Instead, I think other actions he makes are truly, unambiguously morally reprehensible, repugnant. Presumably, Michael never tells Kay about Apollonia. “What’s done is done,” he’d think to himself—even if Kay would find that relevant, important information.

Even worse, he lies to Kay, telling her that he didn’t kill Carlo, when he in fact did have him murdered. And he murders Fredo, putting his own brother to death for his betrayal. A better man, a more upright leader—a man like his father—would have found more noble responses, a higher road. And perhaps he never would have found himself in those situations in the first place.

Beyond that, we see him make unforced strategic errors. There’s a scene where his capos ask him to break off to their own families. Michael declines, and cites reasons he can’t explain to them—asking his lieutenants to trust him, without adducing his reasoning or strategy.

Of course, this decision to withhold information made sense practically from Michael’s perspective—there were secrets and plans he couldn’t yet reveal—but it virtually guaranteed the future betrayal of one of his lieutenants.

Vito Corleone imparted strategy, tactics, doctrine, loyalty, and the importance of family to his son. This is admirable, and together they did well at solving the succession problem.

Vito couldn’t pass on his virtue, though. I’m not confident that Michael even saw those qualities in his father. Perhaps, I imagine, he was blinded by his memories of his father as a kid, the patterns laden in their family. That he could see his father up close and personal in one sense, as his son and successor, but not from other angles, ones we are privileged to as an audience.

When I say that Vito Corleone is one of my heroes, it’s not because he’s a criminal, a mafia leader. It’s because, at the end of the day, I see his virtues—the lengths he went to care for his family and his people, the sacrifices he made for them, and the adherence to his own moral code.

Despite that—and Marlon Brando’s lifetime performance as The Godfather—his son Michael makes for a far more interesting character dramatically, at least to my mind.

Coppola as Creative Influence

I’ve found learning about the history of the making of the Godfather films fascinating and inspiring from a creative perspective.

The project was not popular in its gestation with Hollywood executives, who scorned its existence, and attempted to stifle its gestation with simpler, lower budget forms. Coppola stood strong, using all of his powers and all of his skills to create the faithful, brilliant, award-winning adaptation we know and love.

I found learning about the process of how Coppola took notes for the project particularly inspiring, a process that Tiago Forte recounts in detail here:

Coppola’s strategy for making the complex, multi-faceted film rested on a technique he learned studying theatre at Hofstra College, known as a “prompt book.” He would start by cutting and pasting pages from The Godfather novel into a three-ring binder. Once there, he was free to add notes and comments that would later be used to write the screenplay and plan the production design.

Families and Lines

The Godfather has also prompted me to consider and reconsider the nature of family, the value of having children, a lineage and line.

For much of my life, I haven’t wanted children. Still, I’ve had tremendous inner conflict about this issue, and it continues to be something that I weigh.

We’ll see what fate holds for my life, what manifests in time—but I will say that The Godfather paints a very particular image of family and fatherhood, one that inspires me, even if begrudgingly.

I see Vito Corleone as a man that thinks in decades and centuries, who cares for the impact he makes through his life for his family, his people, and his nation.

He shares with his son that he had hoped that Michael would become a senator, a governor, or a President—his regret that his son ended up needing to replace him, to carry on the family business. Michael says “we’ll get there, pop.” We see them working towards greater power, power for their family and their people.

Power is not commendable for its own sake. But if, in my own life, I truly seek to benefit all beings, to be of service, to have maximum deep benefit—wouldn’t it behoove me to consider raising a family, to have children who can carry on my legacy, who can bring forward my ideas and virtues into new contexts and centuries?

The jury is still out on what decision I’ll make, what my life will hold, but it does make me think!

An Unusual Inspiration for, Influence on The Service Guild

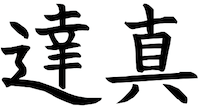

These stories have had an enormous impact on how I view my work as the founder and steward of The Service Guild. My official title is Guildmaster. I like to joke… not joke… that I am The Guildfather. (If I am The Guildfather, Mary Bajorek is The Guildmother!)

Running a Guild is not exactly like running a company, or running a non-profit. Nor is it quite like running a monastery, which I’ve done, or like being the general of a military (which I’ve not done, but have read much about over the years, due to my interest in strategy).

In some ways, creating and stewarding The Service Guild has been more like running a mafia family than any of those things!

Although of course it’s not exactly like that, either. I’ve taken the Buddhist Five Precepts—I’m not interested in lying, or stealing, or murder. I don’t want to commit crimes. I don’t want to do evil.

But I do want to create organizations that are actually effective, and I would be foolish not to take inspiration from where I find it. And I do take inspiration from the fictional representation of these cultures and organizations in Puzo’s novels and Coppola’s films.

As my friend Andrew pointed out, the Italian people were discriminated against in earlier times. Racism and prejudice limited what they could do in America through conventional avenues. A man like Vito Corleone (admittedly a fictional character) wished to care for his family and his people, irrespective of the circumstances they found themselves in. He turned to illegal and sometimes immoral means as a way of serving his family.

We might not approve of those actions, but they are understandable, and we can have compassion for them. And we can applaud and learn from his virtues, even without endorsing his actions wholesale.

There’s a lesson I’ve learned in my life. Your greatest heroes can—will—make mistakes, have vices, problems, blindspots. A hero can still be commendable and inspiring for their virtues, even if we take into account their vices, even if we disapprove of their moral failings.

Similarly, even the greatest villain can have strengths or even virtues; an evil person can still teach us something about how to live well in this world, even if only by counterexample.

I’ve practiced this skill well—learning virtues from whoever I meet, whatever other aspects of their character, whatever reproachable actions they may have taken; taking inspiration for the life I wish to live wherever I find it.

The way I see it, the mafia—and criminal organizations more broadly—have excellent social technologies built in. I don’t have to endorse their means or ends in order to see that their social technologies are often effective. And some of those social technologies can usefully be adapted to other contexts, like The Service Guild.

Here’s a specific, practical example of a way I’ve been inspired by The Godfather. Take the character of Tom Hagen. Hagen is Vito Corleone’s adopted son, and a lawyer. After completing his education, he asked Don Corleone to join the family business, and eventually became the Consigliere. A Consigliere is a counselor, a trusted advisor.

The Don is the moral leader of the family; the Consigliere is a combination strategic advisor, practical counselor, and fixer. He is the face of the family to the world, the governments, the family’s friends, allies, and enemies. His job is to solve problems in peacetime and wartime, to help the family to survive, and—the way I see it—to be smarter than the Don.

In a crime family, it makes sense to have as few parties as possible at the very top. If someone within the family who knows its secrets betrays you, the family is done for. So U want only one Consigliere, and they have to somehow be beyond reproach, incorruptible. Tom Hagen owed his life to The Godfather, who adopted him as an orphan and took him in as his own son. He would never betray the Corleone family.

I took inspiration from this role, and asked two of my close friends and allies—Xuramitra Peter Park and Zencephalon Matthew Bunday—to be Consiglieres to The Service Guild. Unlike in a crime family, we can have more than one close, trusted advisor. They each offer different perspectives, bring different experiences and backgrounds to their role. Together, they make an excellent team that has repeatedly helped me to solve meaningful problems that affect The Service Guild. We are a stronger organization for their counsel and friendship.

Conclusion

I see my relationship to the Godfather films and novels as one that is Soulmaking (in the sense of Rob Burbea’s work).

I see stories as holding clues for our soul, signals of where we are drawn towards. And for whatever reason, the Godfather universe has had some of those clues for me personally.

This may surprise U, but it hasn’t surprised me. I was once a monastic who took inspiration from military strategy, who had a hero in John Boyd, who found solace in the war stories of Ender’s Game. Now, at this juncture of my life, as the leader of a young organization—The Service Guild—I take inspiration in Vito Corleone, and caution in his son Michael.