Strategy was largely developed in two domains: warfare and business. But there’s nothing intrinsically violent, war-like, or even zero-sum about strategy. I often say that if you become interested in meditation, as I have, you will inevitably encounter Buddhism. As a contemplative tradition, Buddhism has taken meditation and meditation instruction quite far. But you don’t need to become a Buddhist to meditate.

Similarly, if you are interested in strategy, you will inevitably encounter military and business strategy. That doesn’t mean you need to enlist in the military, or sprout pointy hair. Those domains have simply developed strategy to a very high degree.

I became interested in strategy when I was the Assistant Executive Director of a small non-profit organization, the Monastic Academy. I wasn’t trying to conquer the enemy on the battlefield, or maximize revenue in a competitive market. I just wanted to figure out how we could actually succeed at our goals.

I wanted to better understand the challenges we were facing as an organization. I wanted to develop a sense of how I fit into that organization, and what actions I might realistically take to resolve our challenges. I wanted to understand how to work effectively—how to use my time, energy, and skills. I wanted to understand how to coordinate effectively with other people and organizations. I had questions like:

- How can I use work as an opportunity to grow individually?

- How should I decide which tasks to take on, which projects to prioritize, which goals to set, which problems to solve?

- Who should I work with? Who makes for a good team member?

- How should groups of people prioritize what to work towards, and coordinate to accomplish their goals? How should we organize ourselves as a team?

- How can I coordinate effectively with other organizations?

- How can someone acquire resources in an ethical and efficient way?

- What is the most effective and sustainable way to scale teams or organizations?

- Where does organizational culture come from?

These questions—and the answers I found—belonged to a domain we might call Strategy.

William Dettmer defines strategy as “the means and methods required to satisfy the conditions necessary to achieving a system’s ultimate goal.” I think of it as a suite of tools providing an answer to the question— “How do I (as an individual or a group) coordinate with myself and others to effectively reach my goals?” It’s about coordination with other actors, both individuals and groups, on long time scales, to coherently and effectively reach a larger, beneficial vision.

The authors that have most informed my thinking have been Sun Tzu and John Boyd, Simon Wardley and William Dettmer. I’ve also been grateful to have the support of my friend and mentor Ben Mosior.

I had a series of questions that I really wanted answers to, and I found answers to those questions to my satisfaction. These answers took the form of a collection of mental models that help me understand the world. These models are deeply ingrained in me now: I use them all the time, consciously and unconsciously, and make better choices because of them.

Strategy Tools and Concepts

This post shares the tools that I’ve found most valuable so far. I hope you’ll come away from it with a basic understanding of what these models, concepts, and tools are, and when they are relevant and useful. If you know that Pre-Requisite Trees are good for planning complicated projects, while Burja Maps are good for understanding power, you can pull those tools out when they’re relevant. You don’t need to be an expert in any of these concepts—you can learn them just-in-time.

Accordingly, I won’t explain each tool in extensive detail. I’ll just present the basics of what each concept and tool is, and when and why you might find it useful. I’ll also share links to resources where you can learn more.

If you’re interested in strategy, this post will be valuable to you. Maybe you’re a leader, or want to be one. Maybe you’re doing important work that you want to succeed at. Maybe you’re working with multiple people, or you’re doing work over long time scales.

Whatever the reason, I hope this post will give you a big picture of how different strategy tools relate to each other. I hope it saves you time, spares you some mistakes, and helps you to realize your ambitious plans in the world, for a more beautiful life for you, your organizations and communities, and ideally, the world at large.

Power

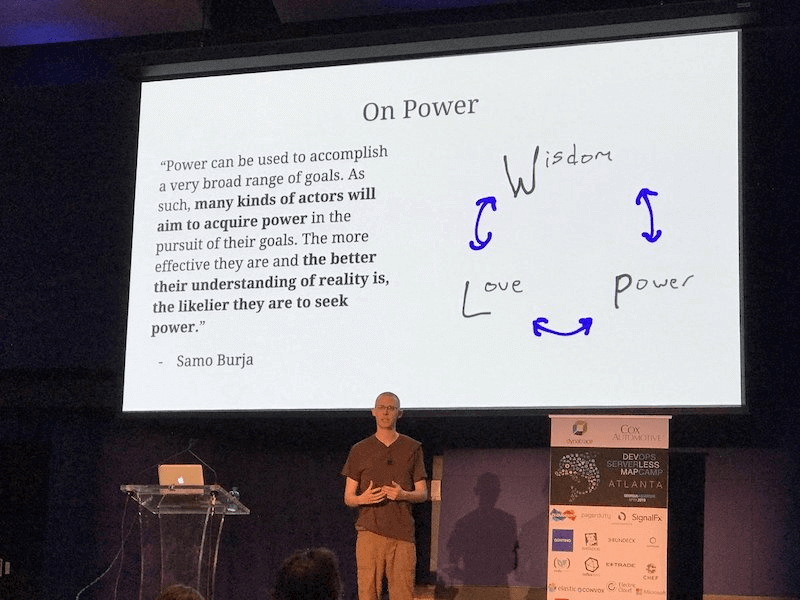

One of the most fundamental things that I received from my training at the Monastic Academy was building a relationship with ambition and power.

When I began my training, I didn’t care at all about power. I think this is like many people in our culture. People avoid power. They don’t want it. Power is seen as something bad, because people have seen it used poorly—for selfish benefit, causing harm to others. That’s how I felt, before I started my training.

Gradually, during my time there, I became interested in power. At the Monastic Academy, they taught me that power isn’t morally evil. It’s actually neutral. It depends how it is used, and by who, to what ends. Used by those who are wise and loving, it can be of tremendous benefit.

Accordingly, if your motivations are to be of service in the world, to be of benefit and to help people, then power is good. You should have power, and use it.

From this perspective, strategy is a suite of concepts and tools that we can use to wield our power effectively.

I wrote more about how I view power in Trustworthy Leaders.

Maximum Deep Benefit

I intentionally structure my projects to create what I call “maximum deep benefit”: helping as many people as possible, as deeply as possible. For me, this is a practical way to honor and act on the Bodhisattva Vows.

Over time, I’ve developed an eye for projects that hit this sweet spot. As a simple example, I like to license my writing, podcasts, art, guided meditations, and other content with Creative Commons licenses where possible, so that other people can share or remix what I made. It’s easy for me to put this license on my projects, and it means that what I created will potentially help a lot more people.

I wrote more about these ideas in Maximum Deep Benefit.

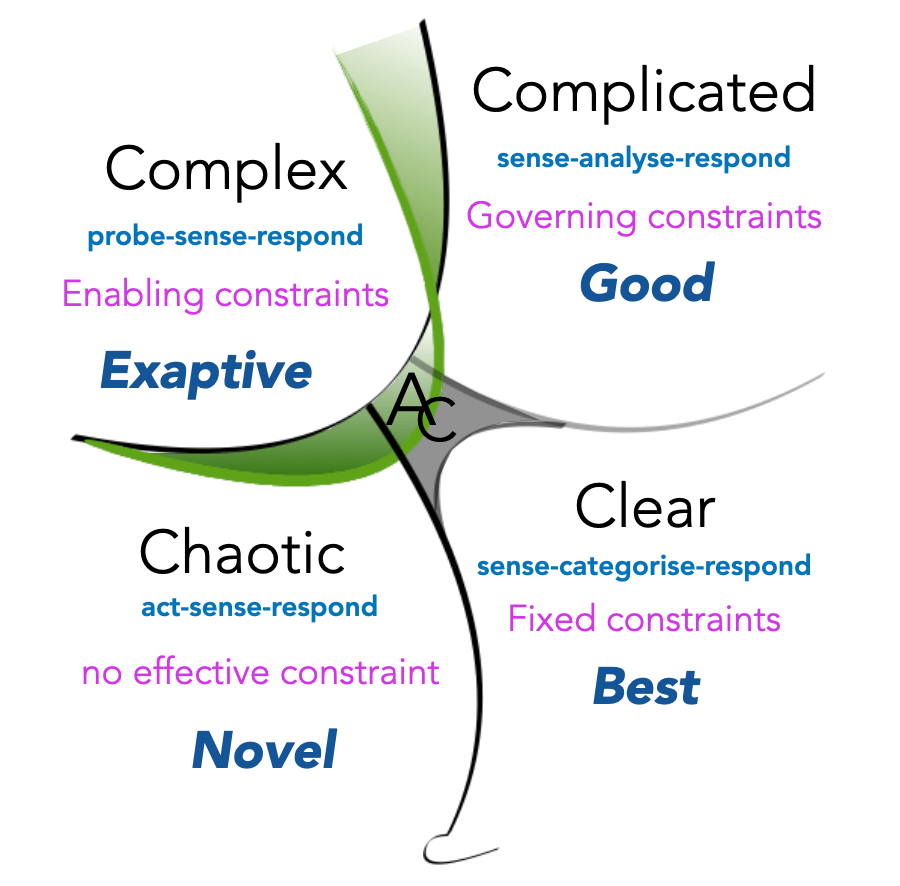

Cynefin

Cynefin (pronounced like “kenevin”) is the Welsh word for “habitat.” For our purposes, it is a simple but powerful framework for making sense of problems. It’s often the first thing I share with someone interested in strategy.

First, it helps you diagnose what kind of problem you are facing:

Clear, obvious problems have simple, well-known solutions. Being hungry means you should eat some food.

Complicated problems have knowable solutions that aren’t easy. For example, if the timing belt breaks on your car, there are clear but potentially difficult steps for replacing it.

Usually, this means either that you should hire someone who is an expert in the relevant domain, or that you should solve it yourself, knowing that you’re getting yourself into a messy situation that might just give you a headache. But you’ll learn a lot!

Complex problems don’t have predetermined solutions. There’s no simple fix, and there are no experts to turn to. Cause and effect relationships can be determined, but only in hindsight.

Situations involving people are usually complex—for example, how can we help a specific employee to feel satisfied with their work—enjoying the projects they are working on, supported and appreciated on a personal level, and challenged to grow in their skills and capacities?

Do several easy, cheap, safe-to-fail experiments. Listen to what happens, using stories as a guidepost. Look for more stories like THIS, and fewer stories like THAT. If one works, keep going. If one doesn’t, stop! Whether your experiments succeed or fail, use what you learn to inform what experiments you decide to run next.

Chaotic problems are characterized by randomness, instability, noise, turbulence, and rapid, unpredictable change. There are no solutions to chaotic problems to be found, because there is no relationship between cause and effect at the systems level. The only thing to do is to find a way out, back to a more ordered situation.

The classic example of a chaotic situation is a war zone, where violence and shifting power puts your life in danger. A war zone is random, chaotic, brutal, vicious—the violence is senseless, cruel in its arbitrariness, its unpredictability, its uncaring brutality.

In the business world, an example might be having your company acquired. New management comes in, shifts the company’s vision and goals, reorganizes departments, fires some managers and employees, and brings in new employees.

A chaotic situation is a highly unstable environment. Stabilizing the situation as soon as possible is the top priority. Any action that helps you stabilize the situation is better than inaction. Take quick, decisive action and try to get out of the chaos as soon as possible with as little damage done as possible.

Although chaos is largely understood to be undesirable, it doesn’t need to be. It can lead to novel patterns and solutions, and can even be entered deliberately. Either way, it’s a transitory state, and you can’t stay in it for very long—nor would you want to.

Disorder is when you don’t know what kind of problem you have. Not knowing what kind of problem you’re facing can lead to inaccurate diagnoses and misguided solutions. For example, you might mistakenly propose a simple solution for a complicated problem, or a complicated solution for a complex problem. Taking the time to accurately diagnose your problem, or its different aspects, means that you can leave disorder and begin to approach the situation sensibly.

Each of these diagnoses naturally suggests how you might approach a solution.

Cynefin also provides a scaffold which helps you understand other, more complicated strategic tools. For example, I find implementation trees, a tool from the Logical Thinking Process (described below), useful in the complicated domain. I allude to the Cynefin framework in many of the descriptions below.

You can read more about Cynefin in Liz Keogh’s Cynefin for Everyone!.

Iteration

Leaders often have big visions, and create detailed plans to realize those visions. While having vision and direction is definitely helpful, elaborate plans run the risk of decreasing your adaptability. You might make a five year plan and stubbornly stick to it no matter what, even when circumstances have shifted significantly, such that your vision and goals have become outdated.

Good strategy is iterative. You steer in a direction and periodically adjust. You sense into the present, try to make sense of what’s happening, make a decision, and then act on it – and then repeat that same cycle.

This insight, that strategy is iterative, is the core of John Boyd’s OODA loop. OODA is an acronym for Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act. This can be as simple as cycling through these steps, but these simple elements can become much more complex.

I wrote more about John Boyd and his OODA loops in The Strategic Theory of John Boyd.

Conditions-Consequences

Much of strategy is concerned with accomplishing goals. Unfortunately, our default approach to accomplishing our goals is suboptimal.

Most people try to achieve a certain goal (end) and find a way to get there (means). This approach does work. That’s why it’s at the core of most organizational goal-setting rituals. But it is very fragile. It tends to work well in the simple or complicated domains, but does not do well in complex situations. The best laid plans often prove to be shiny, brittle failures.

Instead, it’s better to recognize that the future is uncertain. There are many possible outcomes; it’s difficult to predict what will happen. Knowing that, you can cultivate conditions that will contribute to good consequences in most scenarios. This is the conditions-consequences model.

I’ve found that a mix of both means-end and conditions-consequences is the most resilient approach. Know your goals, but don’t get tied to them. Be willing to adapt: to add, drop goals on the fly, and totally rearrange circumstances. Be aware of what ideas, skills, activities, and relationships seem valuable in a wide range of scenarios, so that you can cultivate those conditions, like a gardener tending to a bed of plants, even when there is uncertainty or change. For example, cultivating your understanding of the concepts and skills described in this post!

I wrote more about Conditions-Consequences in Means-Ends, Conditions-Consequences, and the Game of Risk.

The Expected and the Unexpected

The concept of the expected and the unexpected, or the orthodox and the unorthodox, comes from Daoist strategy. It is a translation of the Chinese words cheng and ch’i.

As an example, Teslas have standard car features like chairs, but also include ‘bioweapon defense mode’ buttons. Chairs are expected. Biohazard modes are unexpected.

Mastering standard operating procedure is table stakes for competition. Competitors who also have a flair for the dramatic and unexpected will consistently beat those who merely do what is standard practice.

For a more personal example, part of my work in the world is to spread love—to share the technique of loving kindness meditation and the other brahmavihārās broadly and deeply.

I have weekly meditation events, recordings of guided meditations, and a book on loving kindness. This is all expected—other loving kindness teachers have similar offerings.

But I also have some unusual offerings. I have recorded music videos that aim to inspire people to practice loving kindness. I run mettā dance parties, where you can combine the meditation technique with dance and movement to excellent music. Long-term, I want to create “mettāwave” music—a variant of progressive trance and deep house music that uses lyrics and sounds designed for loving kindness practice. All of these are unexpected, unorthodox for meditation practice, but are effective complements to the more typical, expected best practices.

Combining excellence at the orthodox with novel, unorthodox approaches will create a larger, more beneficial impact than either the orthodox or the unorthodox alone.

You can read more about the Expected and the Unexpected in Chet Richards’ book Certain to Win (my notes).

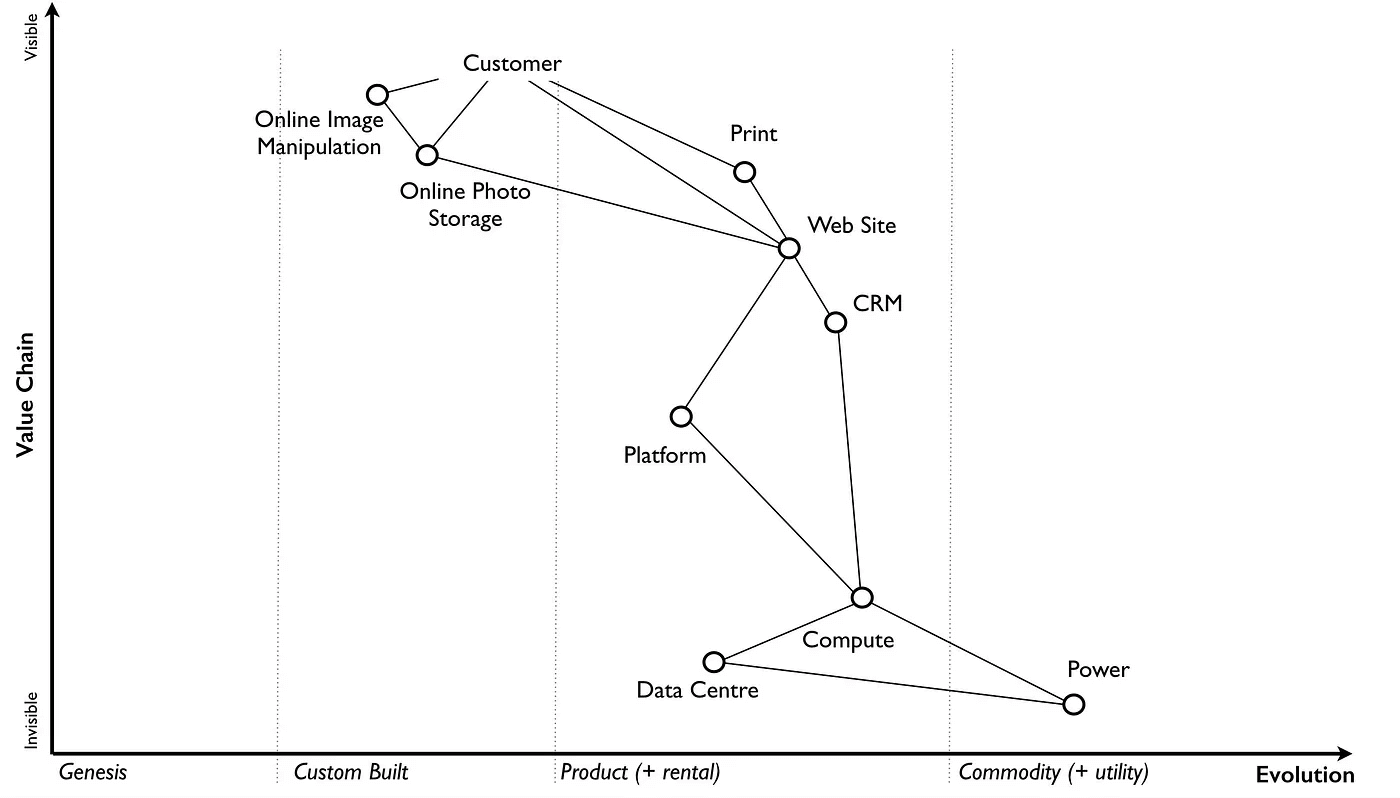

Wardley Mapping

Ben Mosior says that Wardley Maps help you understand things you don’t, but should. The first thing Wardley Mapping provides is a visual artifact, with two axes.

The first axis, the y-axis, is the value chain. You identify who your users are, what their needs are, and how you’re going to meet those needs. The user is the anchor, at the top of the map. Their needs are connected to the user, and anything you use to meet their needs—components—are connected to those needs, as a series of dependencies. These components are more or less visible to the user.

The second axis, the x-axis, charts evolution: a predictable set of trends about how components change over time in a market subject to supply and demand competition. Components—ideas, skills, resources, materials—are completely novel when they first emerge. They aren’t well understood—they are rare, unpredictable, and unreliable. Over time, they gradually become more well understood, well-distributed, predictable. This process is a cycle: as components become more reliable and well understood, it becomes possible for new ideas and technologies to emerge.

For each component in your value chain, you ask, is it brand new, and not well understood? Or is it more like electricity, which is ubiquitous and well understood?

There are a variety of characteristics that components in different stages reliably have. Knowing these characteristics changes how you orient towards them, and shapes the decisions you make.

Wardley Maps help you to understand the landscape of what you’re mapping, and to make better decisions. For example, a common use case of a Wardley Map is to answer the question “Should I make this component myself, or outsource it to a product or service?” You probably don’t want to make your own electricity, but your team might decide to write its own custom software.

A Wardley Map surfaces questions like:

- “Who are our users?”

- “What are their needs?”

- “How are we going to meet their needs?”

- “What stage of evolution is this component in?”

- “Should we build this component ourselves, or rent/purchase it from another company?”

- “How well do we understand this aspect of the landscape?”

Asking and discussing questions like this is invaluable if you’re working on a team of collaborators. Rather than making individual decisions isolated from a larger context, a Wardley Map helps you and your collaborators make sense of the larger landscape you’re working within, and frame your decisions in that context.

This also makes it easier to make decisions. Making decisions as a group can be a long, confusing, frustrating process. Having a visual artifact handy, even a very rough one, simplifies group decision-making dramatically. It becomes much easier to have a calm and efficient reflection on what’s true now and what to do next.

Once you know how to make a map, mapping becomes a useful tool for thinking about making strategic decisions. There’s a whole set of ideas, principles, and best practices associated with using mapping as a way to think strategically.

You can learn more about Wardley Mapping by reading Simon Wardley’s book, available in a variety of formats here.

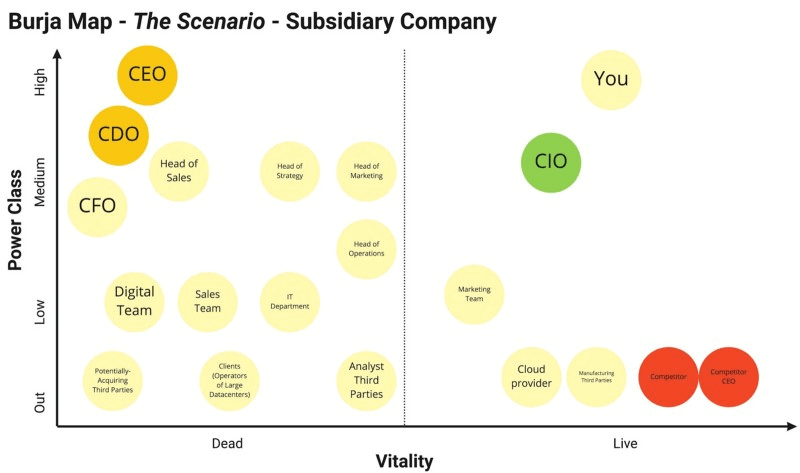

Burja Mapping

To accomplish important efforts, you will need to understand power. You will need to acquire political capital, and use it to bring about a meaningful vision.

Samo Burja’s Empire Theory has helped me to understand power dynamics. It’s also proved useful for interpreting the workings of other organizations we’ve encountered. I’ve found it useful to make visual representations of these landscapes of power, which I call Burja Maps.

While Empire Theory contains many valuable reflections, the three key aspects I decided to represent visually with maps were the relative power class, vitality, and alignment.

Power is understood as relative within the scope of an “empire” or power landscape. A CEO is high power within her company, but low power within her local grocery co-operative. High power is being at the center of an empire; low power is being at the edge.

Vitality refers to Burja’s distinction between a “live” and “dead” player:

A live player is a person or a tightly coordinated group of people that is able to do things they have not done before. A dead player is a person or a group of people that is working off a script, incapable of doing new things.

Lastly, alignment is relational. An actor (whether an individual or group) is an ally, neutral, or an enemy in relation to you and your domain of power.

Burja Maps help you to interpret the current power landscape, and decide how to move forward. You want to come to the point where you can see these power dynamics with ease. It’s as if you were doing a math problem with mental math – no pen and paper needed. When this skill is that easy, that fluid, you can begin to develop your own intuitions for power dynamics.

You can read more about Empire Theory in Samo Burja’s paper Great Founder Theory. I wrote more about how I visually represent his observations in my series on Burja Mapping.

The Theory of Constraints

Maybe you’ve heard the word “bottleneck” used before. A physical bottleneck constrains the rate at which fluid can be poured out of a jar. You can’t pour fluid out at a rate faster than the bottleneck can hold.

The Theory of Constraints posits that every system has a constraint or bottleneck. You can view these systems in terms of throughput: the rate at which something desirable is created or achieved: the rate of fluid pouring out of a jar, cars assembled and sold from a manufacturing line, blog posts published.

If you want to maximize your throughput, it might be tempting to think, what if we just got rid of the bottleneck? But that’s impossible, because according to the Theory of Constraints every system has one, even well-functioning systems. There will always be a constraint.

If you don’t know what your constraint is, you’ll be tempted to make suboptimal interventions—like adding more fluid into the jar from the bottom to speed up how fast you can pour it out, even though the bottleneck is still constraining the rate of pouring, and you can’t actually pour it out any faster.

But if you identify what your constraint is, you’ll make better decisions. The Theory of Constraints prescribes Five Focusing Steps to increase throughput in any system:

- Identify the Constraint

- Optimize the Constraint

- Subordinate the Non-Constraints

- Elevate the Constraint

- Return to Step 1 (Identify the New Constraint)

You can read more about the Theory of Constraints in Tiago Forte’s Theory of Constraints 101 series.

The Logical Thinking Process

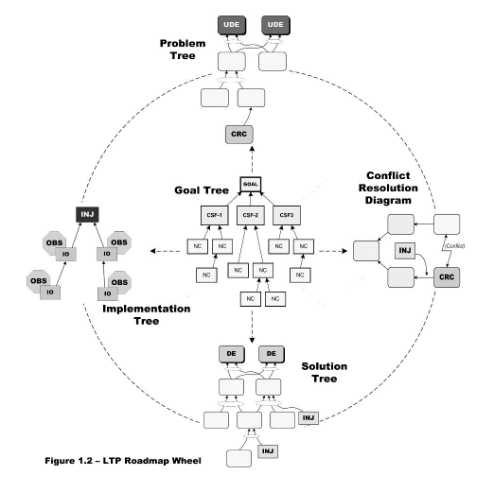

The Logical Thinking Process emerged from the Theory of Constraints. It contains five separate tools for solving complex system problems. Each tool has a different purpose, which answers a different question, which William Dettmer describes as follows:

- Goal Tree – Where do we want to be?

- Problem (Current Reality) Tree – Where are we, actually, and why is there a difference?

- Conflict Resolution Diagram (Evaporating Cloud) – What prevents us from curing the problem now, and how do we overcome it?

- Solution (Future Reality) Tree – What can we expect to happen if we apply a “fix” to the problem?

- Implementation (Prerequisite) Tree – How do we make the solution happen—that is, execute the solution?

These tools were originally designed to be used in sequence, but I’ve found they can be used effectively independently, too. I’ve made the most use of conflict resolution diagrams, implementation trees, and problem trees, in that order.

I wrote more about the Logical Thinking Process in general in The Punk Strategy Guide to the Logical Thinking Process.

Alliances

Succeeding in any strategic endeavor will require alliances with other actors: working together to achieve shared goals.

Samo Burja makes a distinction between narrow and broad alliances:

Two players can cooperate in one domain while battling in a different domain. I call this a narrow alliance. When two players are coordinating to achieve most of their goals and no longer contest one another, I call it a broad alliance. Narrow alliances are the default between most players in an empire, whereas broad alliances are unusual.

While both forms of alliances are helpful, broad alliances are invaluable. Cultivating such relationships over time is the conditions for good consequences.

These allies might be in your organization, or they might be outside of it. Either way, you want to stay in touch with your allies, and find win-win outcomes as frequently as possible.

I wrote more about alliances in The Art of Alliances.

SWOT

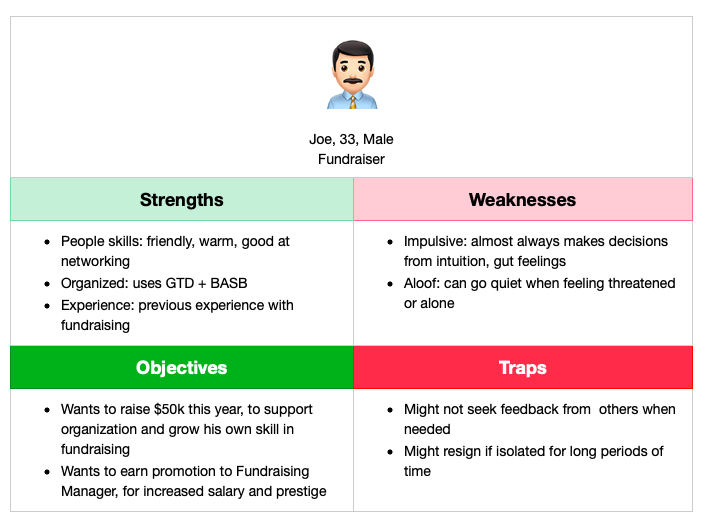

When I first heard of SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats analysis), I thought it was sort of stupid. Like many 2×2’s, it can be used blindly. Moreover, I was confused by the words “Opportunities” and “Threats.” I wasn’t sure from those terms how they differed from Strengths and Weaknesses.

However, when I started exploring Burja Mapping, I realized that SWOT’s are actually incredibly useful. As Simon Wardley says, “The problem with SWOT isn’t that it is useless but instead we apply it to landscapes we don’t understand.” Burja Mapping helps us to understand the landscape of power. From that place, we can use SWOT to understand people’s strengths and weaknesses in a useful way.

I find it easier to think of Opportunities as Objectives, and Threats as Traps. What goals does a person have? Given their strengths, weaknesses, and goals – and your own – what traps might you two fall into together?

I’ve found it very useful to think about the people I’m working with in terms of SWOT’s. It can also be useful to consider the SWOT’s of teams or organizations.

I wrote more about SWOT’s in On the Use and Abuse of SWOT Diagrams.

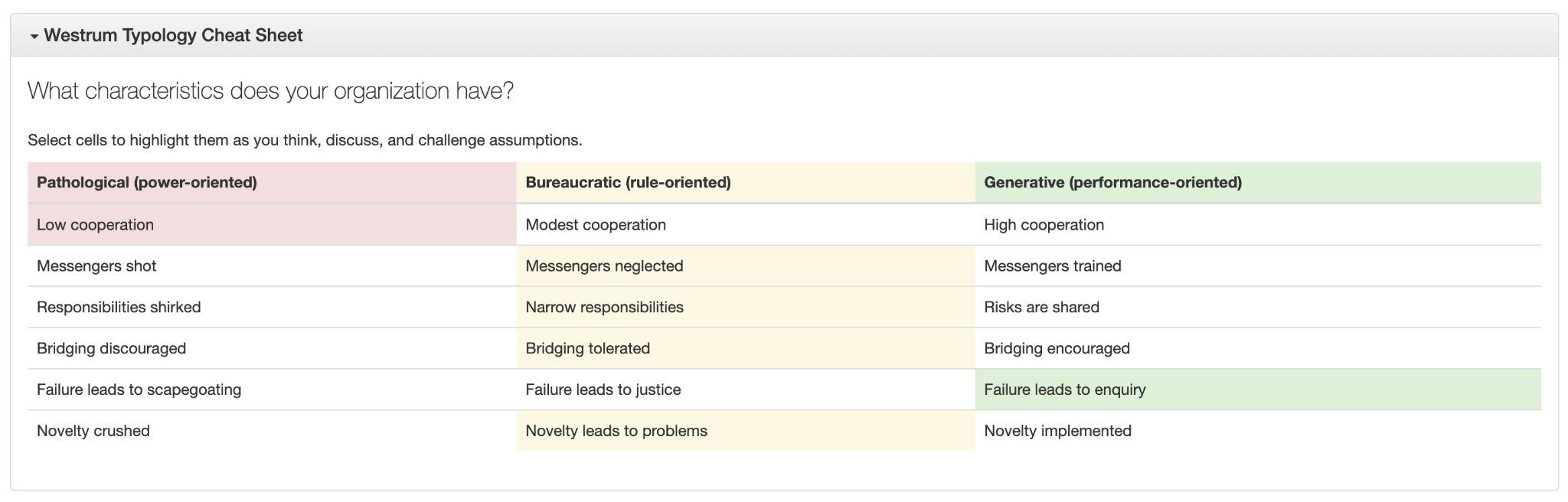

The Westrum Typology

In 2004, Ron Westrum published a paper, A typology of organisational cultures (notes). It posits that the habits an organization has around information sharing are predictive of many elements of an organization’s culture. It also included a typology for comparing organizations and their cultures.

The Westrum Typology has been extremely useful for understanding many things, but in particular, it helped me to understand how to collaborate and coordinate effectively with other organizations. In particular, fast information flow is extremely important. Constantly be asking “who needs this information now?,” and be sure that that information flows to the relevant individuals or groups, even if backchannels are needed.

I wrote more about the Westrum Typology in Applying the Westrum Typology to Coordination.

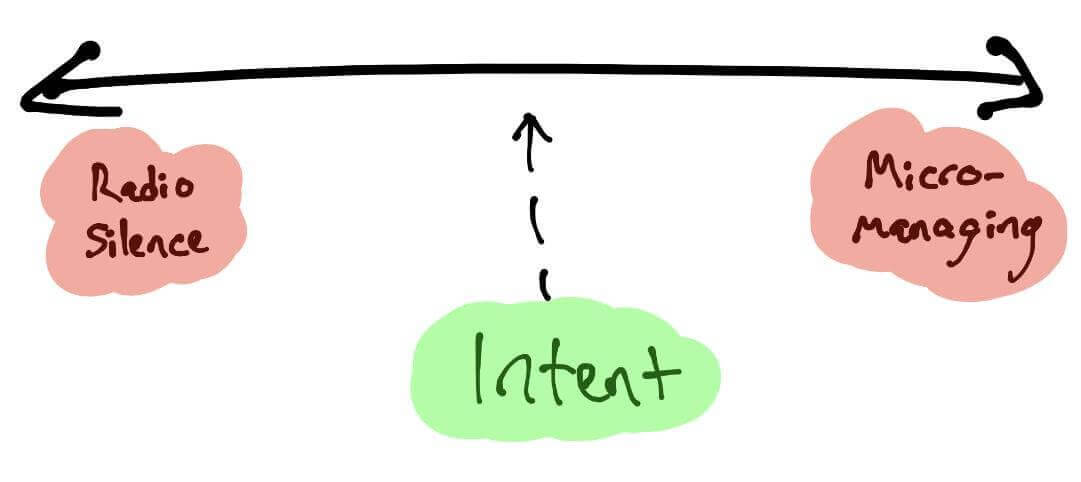

Commander’s Intent

Leadership is challenging. It’s easy for me personally to fall into a common trap: micromanaging. The other risk is that I will overcompensate for avoiding micromanagement, and basically leave subordinates to their own devices, without any input or feedback.

Commander’s Intent strikes a terrific balance between these two failure modes.

Intent is the best approach to use when there is trust between commanders and their subordinates. This can take months or years to develop.

If that trust is present, each project and circumstance is an opportunity for the leader to communicate their intent. They should tell their subordinates everything they need to know: what their goals are, any relevant facts and figures, any hard constraints or needs. Then, when both the commander and subordinate have a shared sense of understanding, the subordinate can elect to accept or decline the mission.

If the subordinate declines the mission, it means that they have serious reservations and many things need to be reconsidered. Doing so should be the exception rather than the norm.

If they accept the mission, there is a shared understanding that the subordinate will do everything in their power to realize their commander’s intent. The commander isn’t concerned with the minute details of how the mission is accomplished, so long as it is accomplished.

The subordinate is empowered to make an effective decision quickly, without pausing to consult their commander. They can use all of their creativity—and their on-the-ground understanding of what’s really needed—to successfully complete the mission.

Commander’s Intent is useful not only for leaders, but also for followers. As a follower, your goal should be to ascertain a complete understanding of your commander’s intent, and to be able to creatively execute that intent using your own intuition as well as any emergent circumstances.

One is always a leader in some contexts, and a follower in others. That’s why it is useful to master following, so that you can lead well – and master leading, so you can follow well.

You can read more about Commander’s Intent in Manage Uncertainty with Commander’s Intent.

Ideal Present Design

Jabe Bloom’s Ideal Present Design is a practical approach to applying Conditions / Consequences thinking. It helps you assess and improve your current situation, steer towards positive outcomes in the future, by asking: what can we do now to address our current problems, avoid predictable challenges in the future, and increase the likelihood that we will find ourselves in desirable futures?

You can read more about Ideal Present Design in Ben Mosior’s introductory post here, or watch him give a short introduction here.

Conclusion

Thinking strategically has helped me to gain power, and to wield it more effectively. I see things better, ask better questions, and make better decisions.

The tools and concepts I’ve shared here are the ones I’ve found most useful so far. It is my great hope in sharing this post that it helps you with your own work in the world, so that you can think strategically and use your power for tremendous benefit.

May we all grow into the fullness of our power. May we wield our power with wisdom and love, for the benefit of all. ❤️

Additional Resources

- Strategy with Ben Mosior – Reach Truth Podcast: Tasshin and Ben Mosior discuss the concepts and strategies that Ben introduced to Tasshin.

- Learn Wardley Mapping: Wardley Mapping is a tool and framework for applying strategy in competitive environments, including but not limited to the business world.