Most Western strategic thought takes place in a means-ends framework. We have a particular goal (win this war, defeat this competitor, earn this degree…); we consider the best possible plan to achieve that goal; and then we execute that plan. There’s a reason that we take this approach: it works.

Means-ends seems to work especially well in stable and/or non-competitive environments. However, when you introduce complexity, change, and/or competition, the means-ends approach works less well. Failure is common; despair abounds.

In this post, I’ll discuss an alternative to means-ends strategic thinking: conditions-consequences. I’ll explore these two strategic modes through the game of RISK, and discuss the broader implications of using conditions-consequences based strategies.

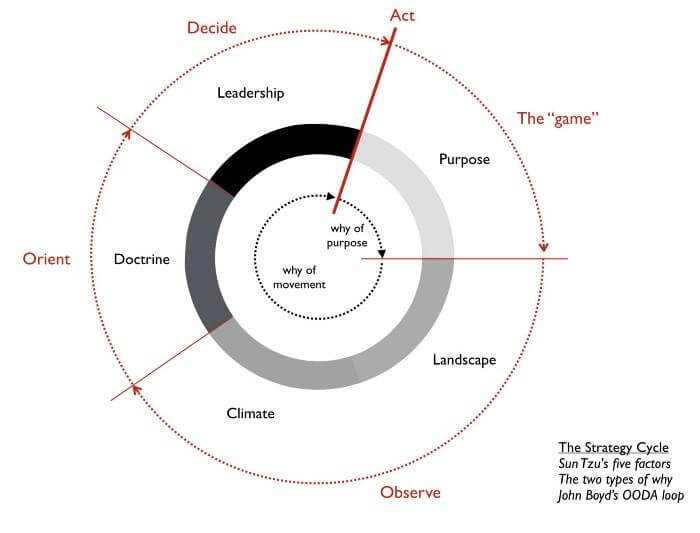

If you’ve read this blog, you’ll know I make a lot of Wardley Maps. Simon Wardley’s mapping techniques are rooted in previous strategic thought, especially Sun Tzu and John Boyd.

Strategy Cycle courtesy of Simon Wardley, CC BY-SA 4.0

When asked about his recommendations for reading about strategy, Simon Wardley gives a few words of advice before cheekily recommending Sun Tzu’s The Art of War above and beyond “the endless gibberish on strategy, leadership and organisation that seems to be commonplace.”

I’ve read Sun Tzu several times. I especially enjoy reading it on audiobook, because it’s short and it feels like I digest it at a deeper level through listening.

A while back, Jabe Bloom recommended that Ben Mosior read a scholarly study of Sun Tzu: Derek Yuen’s Deciphering Sun Tzu: How to Read The Art of War. I haven’t read the full Yuen book yet, but everything I’ve read and heard says it’s wonderful. You can read Callum Flack’s review here or Ben Mosior’s notes here.

Yuen describes means-ends strategic thinking, as well as an alternative approach: conditions-consequences. With this approach, you recognize that the future is unpredictable, and that in fact, there are many good outcomes possible. Rather than getting overly attached to a specific outcome or scenario, you create conditions that lead to good consequences. Instead of intervening, you create the conditions that make the consequence inevitable.

This method is actually quite simple. Reading Yuen’s book helped me to see it everywhere. However, because the Western strategic model, means-ends, is so ingrained in our thinking, it may seem abstract or difficult to understand. So let’s make it concrete with a very specific (and relatively fun) example: playing a game.

Games are a terrific way to explore and learn. It’s easy to stay attentive, curious, engaged, and excited when you’re playing a game. Different games lend themselves to exploring different concepts and ideas. For example, James Stuber describes using the game of Mini Metro, a transit planning game, to learn about the Theory of Constraints (TOC).

Risk, the classic game of military strategy, can help make ideas from The Art of War much more vivid, and to put them into practice, especially the shift from means-ends to conditions-consequences.

When you play RISK, you play on a map that contains territories and routes between them.

Each territory is possessed by a player, with a unit count (their armies). You can start the game a couple different ways, but a quick way is to receive a random but equal allocation of territories to each player across the map.

Each round, you get a number of reinforcement units to deploy to your territories. If you hold all the territories inside certain boundaries (e.g., all of North America), you receive some additional number of units each round. The trouble is that you must then defend those territories to maintain full possession of them and continue receiving the additional units. That bonus for territory groups is one of the fundamental mechanics for winning the game. Other players will actively thwart your attempts to secure those territory groups, because they obviously don’t want your strength to snowball over several rounds.

Here’s an example scenario that illustrates means-ends thinking vs. conditions-consequences thinking: let’s say that at the beginning of the first round, you are randomly allocated two of the four territories for South America.

If you’re stuck in means-ends thinking, you might reasonably decide your objective is now to take South America. Accordingly, you pour all your strength into those territories. You attack the remaining territories so you can secure the full territory group. You move quickly, but it results in a weak defense when another player invades. You pour more and more strength into the remaining territories, because you are committed to South America. The other player crushes your forces. You have failed.

However, if you shift into conditions-consequences thinking, you might proceed slightly differently. You recognize that your current territories have a disposition that might allow you to take South America. You also recognize three alternative places where you could concentrate your forces within attacking distance of territory groups. You decide your immediate objective is to husband your strength (conserve resources and use them frugally), because if you have more units than your opponents (the conditions), you will win (the consequences).

To be near the goal while the enemy is still far from it, to wait at ease while the enemy is toiling and struggling, to be well-fed while the enemy is famished—this is the art of husbanding one’s strength.” – Sun Tzu, The Art of War

So, your opponents start battling it out for territory groups. One of them deploys a large force and conquers all but one territory in South America (because you built up strength in that territory). The situation has unfolded, and there’s a new disposition. One of the alternatives you identified is extraordinarily weak and nearby. So instead of focusing on South America, you escape with your strength. That strength can be leveraged to retake South America later, when your opponent is weak from fighting with everyone else, or it can be leveraged for another opportunity that presents itself.

As I play RISK, I watch myself flip back and forth between means-ends thinking and conditions-consequences thinking. If I lose, I can without fail look back and see that I got trapped in means-ends thinking. If I stay in a conditions-consequences mindset, though, I will almost inevitably win the game. It almost feels like cheating, because, in the words of Chet Richards, one of Boyd’s disciples, you are Certain to Win.

This image depicts how playing Risk conditions-consequences-style often ends up. Look closely at Asia. With this style of play, you almost always end up with overpowering resources at which point it is inevitable that you will win.

According to Ben Mosior, the lesson here isn’t about world domination, warfare, or even how to play RISK. It’s about strategic non-interventionism.

A byproduct of means-ends thinking is meddling, which always creates a whole host of new problems. Conditions-consequences thinking is certainly about moving when an opportunity presents itself, but the difference is the default focus on the meta-game.

Instead of committing to a plan… (I will do X and then Y will happen)… you commit to a meta-game that will make the consequences inevitable.

In practice, conditions-consequences thinking requires an awareness of which meta-game we need to play for our own projects and teams to succeed. For example, when an inexperienced leader or teammate makes a decision that is certain to be a mistake, it’s tempting to intervene (means-ends). But it’s a meddlesome thing to do, and they certainly won’t thank you for it even if you’re “right.”

Instead, you can acknowledge that their mistake probably won’t be catastrophic, and that the most important thing is their learning and growth (conditions-consequences).

You can sensitize them to what good and bad outcomes look like, let the circumstances unfold, and be ready to help them back up if they fall over. In this way you’ve husbanded your strength — your limited time and attention, as well as the equitability of the relationship — for the most important step: guiding their reflection, learning, and growth.

Sometimes their actions won’t turn out to be a mistake after all. Sometimes they will see what’s going wrong on their own and correct it without your meddling. These are equally good outcomes and the inevitable consequences of the conditions we’ve created.

As you learn to think this way, you’ll discover ever-more circumstances where it applies. You’ll catch yourself meddling, but over time you can learn to be mindful of the conditions you create in your work, in others, and in yourself.

The consequences will speak for themselves.

Special thanks to Ben Mosior for the conversations that informed this post.

Subscribe to my newsletter, my YouTube channel, or follow me on Twitter to get updates on my new blog posts and current projects. You can also support my work and writing on Patreon.