Think about trust and distrust for a moment. How those themes have shown up in your life. The times U’ve trusted someone, and the times U’ve distrusted someone. The times your trust has been betrayed, or U were surprised by what happened.

Perhaps there was a time where U really liked and admired and respected someone, and then they did something that surprised U. That changed how U saw them, interacted with them.

Perhaps there was a time where someone suddenly changed their behavior around U. Or maybe they were resistant to relate to U in a way that seemed straightforward and simple.

Perhaps U’ve been exposed to an unusual group or two in your time. Maybe U weren’t entirely sure if they genuinely had answers to the mysteries of life U had long been seeking, or if they were actually a cult secretly plotting to warp your mind and steal your money and ruin your life. Or maybe a little bit of both?

Are those situations confusing to U? Are U still not sure what to make of them, even after many years?

Trust and distrust enter into all aspects of human relating: making friends, finding collaborators, agreeing to business deals, building communities, signing international treaties. And yet, despite how fundamental these themes are, we generally have overly simplistic models for relating to trust.

When we are young, we have no conception of trust or distrust. We simply have our parents, and the world they bring us into. We are at their mercy, beholden to their care and their strengths and their weaknesses. Gradually, we individuate, but our models still may not include sufficient nuance or complexity.

One model of trust that I personally received was quite simple. People with wisdom, love, and power were trustworthy, and people without them were not. This model was effectively binary. It worked reasonably well, and had its merits. It was conducive to creating a local high-trust community, an oasis within the larger, low-trust society. It inspired me to become more trustworthy—to cultivate wisdom, love, and power.

But it had challenges. Edge cases. Latent problems. What if I simply didn’t trust someone who was ostensibly wise or loving? How did U know who was really wise and loving, anyway? What if I felt like my needs weren’t being met? What if I just felt weird and bad, for reasons I couldn’t explain or articulate?

When I learned about my friend Malcolm’s Non-Naive Trust Dance, it helped me begin to answer the questions I had about trust. As I’ve learned more and more about it, it’s fundamentally shifted the way I see and relate to any situation that involves trust and distrust. And increasingly, I’ve become convinced that NNTD holds important keys for all of us—for our whole civilization, our species, our planet. That developing a more robust, widely adopted model of trust is necessary for a beautiful and kind future.

The purpose of this post is to explain Malcolm Ocean’s Non-Naive Trust Dance (NNTD), its claims1In some cases I am directly paraphrasing things Malcolm has said, but putting them in my own words, or even citing things Malcolm said elsewhere verbatim—but summarizing or presenting them in a differently-presented order that makes more sense to me.

Note that this post serves as my explanation of this material, to myself. Malcolm might disagree or explain things or see things differently! In those cases, consider deferring to his explanations or caveats.about the dynamics of trust and distrust. My goal is to make the theory clear and easy to understand, and to make it immediately applicable in practice.

I hope and anticipate that it will help U to be more capable of relating to trust and distrust in clear, kind, ethical, skillful ways within yourself, with others, and in the contexts U care about.

drawing by Sílvia Bastos, commissioned by Malcolm for Non-Naive Trust Dance—why the name?

An Account of Trust and Distrust

The Non-Naive Trust Dance gives an account of trust and distrust2Or, to use a phrase of our friend Qiaochu’s: “a robust accurate theoretical model” of trust and distrust. Malcolm would go further, and claim that NNTD is a law, a theory, a set of practices—both a protocol, and a metaprotocol. I disambiguate those terms in a separate post., as well as a suite of useful, practical ways to navigate real situations involving trust and distrust.

From the perspective of NNTD, we are learning systems. As we go about our life, we learn from our experience. Because we have different experiences in life, each of us learns different lessons. From those experiences, we have different senses of what we can trust and distrust.

When presented with similar situations, I might be more inclined to trust something, whereas U may be more wary and suspicious, given previous experiences you’ve had. So earning your trust in a given situation will be different than earning mine, or anyone else’s, due to variations in our life experiences.

Framed in terms of Cynefin, trust-building is complex, emergent, rather than simple or complicated. There’s no right answer that we can predict or proceduralize ahead of time. There’s no solution that works in all cases.

What is trust?

Malcolm describes trust as a sense of being able to orient to something (a situation, person, utterance) without any sense of guardedness. In his paper Trust as an Unquestioning Attitude, philosopher C. Thi Nguyen defines trust as the capacity “to rely on something unquestioningly.”

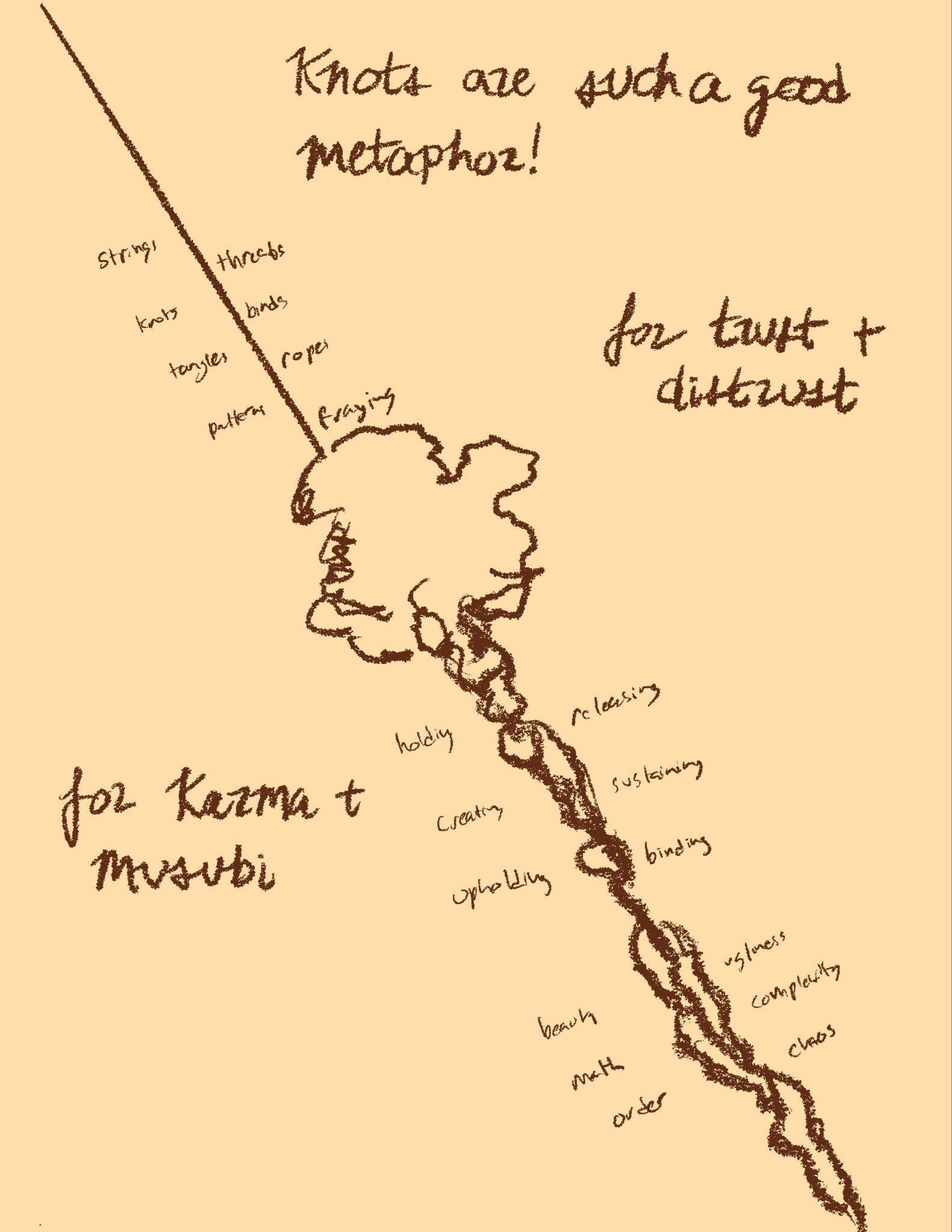

Nguyen uses a climbing rope as his central example of an object we trust. For myself, thinking about trust in terms of rope, knots, and string has also proved to be a resonant, intuitive, embodied metaphor.

Imagine a single, solitary thread of string encircling a small marble. That thread would be very flimsy, and would not hold the marble for even a moment.

Trust is like our sense of whether a knot will hold the object it is tying. Some knots can hold what they are tying well. Other knots are simply insufficient. U just can’t make a single string hold a marble; U simply can’t make a single rope hold up an entire building.

The knot metaphor suggests other implications, also. Different knots work for different situations, serve different purposes. There is often more than one option. But some knots won’t work in some contexts—what works in a business deal may not work in a marriage.

U might have a tangled knot that isn’t doing any work at all. Someone pulled at the knot, or a knot was used inappropriately so that it slips or breaks, and it gets pulled into a tangle that can’t be used as effectively, if at all. It may look like something is there—the strings and ropes are interlaced in a complex way—but it won’t hold any weight. Some trust dynamics can be like this. Something is happening, but it ain’t full-on, real, earned trust.

When a knot is tangled, U can’t just tear it apart, yanking and praying that it will all work out. It takes presence and consideration. U have to look carefully to notice where the tangles actually are. U have to investigate the constitution of the knot. U have to loosen and untangle it gently, carefully.

What is distrust?

Distrust, then, is the visceral, direct, felt sense that U cannot trust something—that U cannot rely on a situation, unquestioningly. It’s like noticing that a shoestring is temporarily but tenuously holding a five pound object. Our body screams: “that won’t hold for long!”

The core of NNTD—the key sentence that contains it all—is “you can’t trust what you can’t trust.”

Or, simply: there is distrust. There is distrust. I’m going to distrust people and situations. People are going to distrust me. And people are going to distrust each other.

People have distrust based on the experiences that they’ve had, and the lessons they’ve learned from those experiences. We carry all kinds of assumptions about what we can trust or not. Those distrusts are real, and U can’t just override them.

I distrust things. I distrust people. Other people also distrust people, things. It’s also possible to distrust situations or environments.

NNTD claims: Distrust is normal. It’s not a problem that there’s distrust. To the contrary: distrust is healthy. U shouldn’t trust everybody with everything all the time! In fact, U can’t.

Here’s a simple example that I like to use to illustrate why distrust is healthy. I think that most of my friends shouldn’t trust me to come and take care of them if they’re sick.

It’s not because I wouldn’t want to. It’s because I travel a lot. I can only be in one place at a time. If I’m in Asheville, I can’t take care of my friends in the Bay. If I’m in Portugal, I can’t take care of my friends in Brooklyn. I want to help my friends, but I can’t do so if they’re sick in another part of the world.

What is a problem is pretending that there isn’t distrust, or shouldn’t be, or that U can just sidestep it entirely.

Here’s yet another way of looking at it: it’s not trust in, it’s trust to. U don’t have binary trust or distrust in someone or a situation, but rather a whole spectrum of ways U experience trust and distrust.

Take this blog post. I trust U to read to the end of this very sentence. I don’t trust U to keep reading this whole post. Most people spend ~3-4 minutes on my website! I also don’t expect U to agree with me.

I’d guess that U likely trust me to be honest in this post. Probably it seems like I’m stating things how I see them, at least.

U may not trust me to know what I’m talking about, or to have anything to say that’s valuable to U in your life. All of this does seem very abstract and heady and philosophical, after all. Then again, perhaps he has a point…

Or, put another way: there’s no such thing as trustworthy. There’s no intrinsic, unconditional, noncontextual trustworthiness.

What is naive trust?

The name “Non-Naive Trust Dance” implies that there are naive and non-naive forms of trust.

Naive trust is when U are completely ignorant of the possibility that your trust could be misplaced or betrayed. Like someone who is new to computers, who isn’t even aware that someone could steal their information about their bank account through the internet. That’s a hard lesson to learn!

But there’s another way that trust can go wrong: when someone has distrust, but they override it. They are “ignoring warning signs in order to deliberately adopt an unquestioning stance.” We might call this forced trust, fake trust, or pretend trust.

Distrust is present because we’ve learned lessons from our past experiences. These are implicit expectations we can’t simply change at will—and we wouldn’t want to even if we could.

For example3I’m using money as an example here because it’s quite simple, and easy to explain. Real life interpersonal situations are often messier and more complex. There will be more of those towards the end of this article!, imagine U ask me to loan U $100. I have an uncomfortable feeling arise in my stomach. I remember the time that U promised me U would do something important for me, but then forgot.

Or maybe I remember loaning another friend money. I had to nag them repeatedly for months before they eventually returned the money. I really needed that money for something! That was an inconvenient, unpleasant experience I don’t want to repeat!

Based on those experiences, I might not trust that U will give me $100 back. It would be forced or fake trust to override my gut feeling, and give U the $100, in spite of my reservations. It’s physically possible to hand U $100, of course. Doing so overrides my distrust, though.

Think of the colloquial saying, “just trust me, bro!” This phrase implies that it’s possible to convince someone to trust something they are demonstrably inclined to distrust or have reservations about. It is possible to persuade or coerce someone to act as though they trusted something they don’t.

It’s also possible to persuade or coerce yourself in this way! U might not even know that it’s happening. U might be pretending even to yourself that U are trusting. We might be subconsciously deceiving ourselves. Buying into our own B.S.

But this is not real trust, from an NNTD perspective. U cannot actually cause someone to trust something they don’t trust.

We might call this “trust wrestling,” in contrast to trust dancing. Trust wrestling is trying to coerce ourselves or others to trust in ways that they simply can’t, because distrust is present.

We might think “oh, I could just persuade them to trust” or “if I could just get them to see a certain way, then they’ll trust this, or this person, this context.”

The NNTD implies, no! U can’t force trust. U can’t persuade someone to trust what they can’t trust. Statements like “just trust me!” or “I’ll try to trust U” are like perpetual motion machines. Things like this will never work, couldn’t possibly! They might seem to work, but they can’t truly work or last sustainably.

To use a knot metaphor: U could theoretically tie a single small string around a marble, and even possibly hold it up for a moment or two—but that doesn’t mean it will last, that it will sustainably hold the marble if U add force or motion. If someone said “just trust me, it’ll hold!”, U’d look at them like they’re crazy.

What is non-naive trust?

Non-naive trust accounts for any distrust that might be present. It does not simply override distrust. Rather, it acknowledges and respects that distrust.

Because distrust is based on past experiences, and the lessons we’ve learned from those experiences, respecting that distrust will look different with each person and in every case.

Imagine a husband and wife. They’re buying a car together for their new home, and are planning on starting a family together. The husband comes from a wealthy family. He’s owned several cars before, but his parents bought them for him, brand new. This is his first car that he’s buying for himself.

The wife comes from a family with far more modest means. She’s only owned one car before, a used sedan which she purchased herself, with money she earned from several part time retail, restaurant, and babysitting jobs. The used car salesman who sold her first car assured her that it was a trustworthy, reliable car, but she found out several months into owning the car that key parts of the engine chassis were rusting away, and needed very expensive repairs. She swore to herself never to trust car sales people again, and to have a repair person evaluate a possible car before buying it.

Clearly, the husband and wife are coming into this situation with very different past relevant experiences.

The wife’s wariness, suspicion, and caution might seem excessive and unnecessary to the husband, who is happy to spend money on a brand new car for their family. The husband’s nonchalance might seem naive and careless to the wife. She’s worked hard for her money. She’s learned the hard way that it serves to be cautious about major purchases.

Without taking the time to understand each other’s relevant prior experiences, and to respect where they are coming from, they might be on the road to a difficult and uncomfortable conversation:

“Just trust me,” the husband says. “It’ll be fine! Let’s just buy the car you like and be done with it all.”

“You idiot!” the wife says. “You always do this!”

…a vicious argument that ends their relationship ensues.

OK, this example is definitely contrived and simplistic. And the dialogue is not very good. But it made me laugh. And I hope U take my point.

We could imagine a different version of the conversation that surfaced the wife’s distrust. Where she felt her distrust was being taken seriously.

The husband might take the time to inquire as to her prior experiences. Maybe they could see if they could find a mutually agreeable path, one that would make the wife feel more at ease about purchasing the new car. Like, just taking the car to a mechanic and having it inspected by an impartial third party.

Or perhaps the husband mentions the existence of Lemon Laws. Lemon Laws protect consumers who purchase defective new cars. As a result, she’s satisfied that what happened when purchasing her old, junky used car won’t happen with her new car.

Or perhaps he asks her what would make her feel safe and at ease. She’s not sure either, so they spend time researching. They look through reviews of the auto sales shop, reliability ratings, consumer reports, and the like. The feeling of being on a team makes her feel safe in a way that she didn’t when she bought her used car way back when. Researching and considering the problem together makes her feel like she’s not alone. Like any problems they might have would be surmountable.

Real life is far more involved and complex. We can find ourselves in all kinds of unusual situations in our lives. Still, these fictional solutions suggest how to apply NNTD in practice.

One could also imagine other creative solutions. Usually, there’s more than one win-win solution.

Importantly, the solution doesn’t just entail deferring to the distrustful person. Sometimes people fear that respecting distrust will necessitate unconditionally obeying the person who is distrustful, or their specific request. To the contrary. The point is to navigate distrust in a way that respects all parties’ concerns, needs, and experiences.

In fact, sometimes, we might both distrust a situation, albeit for different reasons, as a result of distinct prior experiences and lessons.

We need to listen to and respect our own distrust. We also need to recognize, honor, and validate each other’s distrust for us to discover a mutually workable solution.

Here’s an example. Imagine I’ve lost my cell phone, and need to make an important call. I ask a stranger if I can borrow theirs. They hesitate. They don’t trust me to return their phone. I could steal it.

I trust myself not to steal their phone. But they have no basis to trust me. In fact, they may have had previous experiences of being taken advantage of in similar situations, that are causing them to be wary of trusting a stranger.

In that situation, I could say “That makes sense. U don’t trust me! U’ve never met me before. How about I give U my wallet with my ID card while I make the call? Then we’ll swap after I’m done.”

That move acknowledges and respects their distrust as reasonable, and it offers a proposed method for diminishing their distrust, the risk of the situation.

Of course, in real situations, we may have to be more creative, but the principle is the same.

Acknowledging distrust and working with it is a gradual process. It requires understanding where that distrust comes from—what experiences we’ve had that caused us to distrust, and what lessons we took away from those experiences.

We can have non-naive trust when there are no more warning signs, or we’ve acknowledged and respected any distrust that might be present, not only in nice words but in appropriate, fitting deeds.

Here’s a simple example. I value timeliness. If I make an appointment with someone, I like it when people are on time. Alternatively, if they are going to be late, I like it if they give me a heads up. I prefer it if this doesn’t happen very often. I want being late to be the exception rather than the norm.

Imagine that U and I regularly have meetings on the calendar, but that U’ve been late in the past. There were several times where U were ten or fifteen minutes late, and didn’t message me. Not only that, but U missed one meeting entirely. U had forgotten about it. That kind of thing tends to make me feel quite frustrated!

If U were to ask me for a new meeting, I would have some hesitation. Based on my past experiences of U, I might distrust that U would be on time, or make the meeting at all!

However, imagine if U said something like this: “I know I’m not always on time, and that I missed that one meeting a few months back entirely. I know U really care about timeliness and consistency. That’s really reasonable, and it’s fair if U don’t trust me to be on time. However, I really want to meet with U this month, because what I want to discuss is really important to me, and quite urgent. I promise U that I’ll be on time. To show U I’m serious, I’ll give U $50 right now. If I miss the appointment, U can keep the $50. Hell, U can keep $20 anyways as an apology for the times I’ve been late. The money being on the line will incentivize me to remember our appointment.”

In that situation, I would feel that my distrust was acknowledged. My values and needs would feel respected. I would have a tolerable way of dealing with the situation that I distrust. If they are in fact late, as I fear they will be, or forget the appointment again, I get $50!

Another important example might be: imagine U want me to loan U $5. Based on prior experiences, I might have distrust come up that U will actually give me the money back later, but I might be more willing to eat $5 if U betrayed my trust and kept it. It’s not $100 or $1,000!

One solution to distrust is to find trust in ourselves that we “could handle the situation if the issue did occur.” We still distrust the situation. We aren’t faking trust. We’re simply noting that we aren’t ultimately worried about such a scenario. If things go wrong, we can handle the loss.

Conversely, we might want someone else to trust us in a particular way. Say I want to take out a loan from the bank for $500, but get rejected. I might trust myself to repay the $500. I might feel hurt that they rejected my loan application.

Still, I can understand where they’re coming from. Based on their past experiences of other creditors, or their inexperience with me in particular, they have a valid basis for distrust, for rejecting my loan application. I can respect that.

Using money in these examples makes things seem quite simple and straightforward. In practice, the experiences we’ve had in the past that serve as a basis for distrust can be quite idiosyncratic, complex, and difficult to describe. We may not even understand our own distrust in full detail. Moreover, attempts to build trust might actually arouse suspicion, for whatever reason.

That’s why it takes time, care, respect, curiosity, and creativity to understand, acknowledge, and respect distrust, wherever we find it.

What is trust dancing?

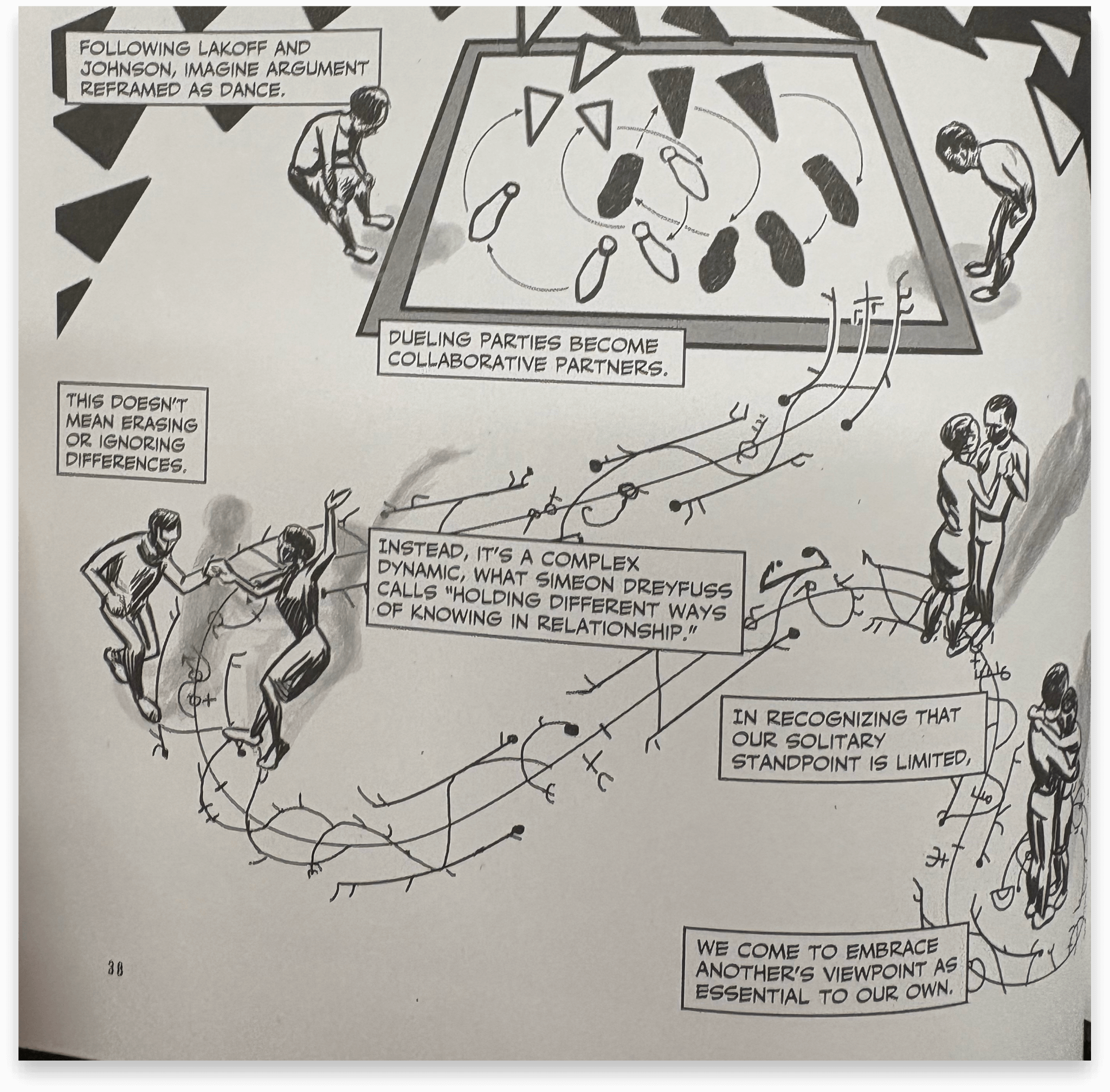

Malcolm uses the term “trust dancing” to describe this process of respecting distrust and building non-naive trust.

The knot metaphor gives a felt sense of the physics-like nature of trust and distrust, but doesn’t necessarily extend intuitively to more complex contexts, like interpersonal relationships.

Dancing works better as a metaphor here. We emergently co-create a response to our situation.

When we dance with someone, we are having a live interaction. Beautiful, enjoyable dancing requires presence and attunement. It demands responsiveness to what we sense and desire, within ourselves and alongside one another.

My friend Eric Chisholm, who is also one of Malcolm’s close friends and long-time conversational partner, is an expert West Coast swing dancer. He found Malcolm’s use of dance as a metaphor “very poignant.” For him, trust literally comes up in dance—it’s not just a metaphor.

“What makes partner dancing a great metaphor [for trust and distrust] as opposed to other activities, is that it is a specific container within which you are in some sense on the same team and forced to interact with each other’s whole dance personality. It is almost entirely teamwork, and what you do has immediate consequences for the other person.

It is a microcosm of the whole larger thing. It is a game where you can’t just automatically cooperate skillfully but you really want to do your best. And at the same time, you can get in your own way and they can get in theirs and you can get in theirs and they can get in theirs.

Or you can have great synergies, and it’s down to their and yours’ specific compatibility with knowledge, habits, assumptions etc. It is largely based on pattern recognition rather than raw experiences of how it is to dance with this person, which is a great breeding place for miscommunication.

In partner dancing, trust is very obvious, immediate, instinctual. As a leader, what do I trust my follower to do or not do? As a follower, what do I trust my leader to do or not do? If a partner gives you an opening, do you trust them not to take it away immediately? Do you feel free to express yourself in the music, or are you bracing for something to go wrong?”

When Eric doesn’t know or trust his partner, he defaults to basic moves—nothing fancy or risky. If he knows that partner is generally jerky and uncomfortable, he protects himself by putting himself in a predictable position, rather than a less safe one that might hurt his body:

“There’s a very basic trust to actually put your weight into a dip or not. Did they support me on the entrance? How much weight are they asking for? These checks are happening in a blink, and if it doesn’t check out, they might drop me.”

“This trust builds over time, over multiple dances. You have repeated encounters with people. You don’t trust them immediately. Over time you’ll figure out what you can and can’t do with other dancers.”

Dancing with one partner is different from dancing with another. Each dancer is different. And the dance that emerges is shaped not only by individual capacities, but the actual levels and shapes of trust and distrust that are present.

“Argument as Dance” — Unflattening by Nick Sousanis, p. 38

Even when we’re not literally dancing, building trust is metaphorically just like this. We have to honor what we know, trust, and distrust about specific people in order to find an emergent response that works for both people, meets them where they are at.

Eric says: “the [dance] metaphor is extremely deep: how people dance is how they live their life.” As they say, “how we do anything is how we do everything.” How we dance is how we navigate trust in all situations.

Trust Dancing in Practice

We’ve discussed the fundamentals of the ideas behind NNTD, its theories. Now let’s put it into practice, and learn some trust dance moves.

Reflect on Trust and Distrust

From a practical perspective, NNTD can be seen as the things Malcolm discovered while he reflected deeply on the situations he found himself in that related to trust and distrust. NNTD is his idiosyncratic way of explaining these things to himself.

Spend six months or a year thinking about trust and distrust. Every person U’ve ever trusted or distrusted. Every group U felt connected to or wary from. Every situation that surprised U or hurt U or still confuses U to this day. Every relationship where U keep having the same stuck conversation over and over again. U may very well intuit some of these principles, derive similar conclusions.

Surfacing Trust and Distrust

One simple, straightforward way to practice the Non-Naive Trust Dance is to notice the ways U already trust and distrust.

Speak the following sentence stems aloud. Proceed one at a time, and complete each sentence.

- I trust Person X to…

- I distrust Person X to…

- I trust Group Y to…

- I distrust Group Y to…

- I trust Situation A to…

- I distrust Situation A to…

- I trust myself to…

- I distrust myself to…

Notice if the sentences resonate in your body, feel true. What effect does saying resonant, true statements have on your emotional body?

This exercise has U practice accessing your own sense of trust and distrust, in the privacy of your own mind, heart, and home. Malcolm also suggests that U can practice accessing and honoring your own distrust by journaling: “to journal about the people in your life and what you think their motives/intentions might be, that they would disagree with… plan not to show anybody.”

In my experience, the sentence “I distrust myself to…” is particularly powerful. Admitting honestly what we distrust about ourselves—how we’ve abandoned or betrayed ourselves in the past, or what we fear about responding to our present and future circumstances—is the first step towards re-building (non-naive) self-trust.

Some further questions for reflection:

- Do U trust yourself to state and share your trust and distrust honestly and accurately, to represent them fully and completely?

- Do U trust the context U are in to receive the truth of your trust and distrust well?

- If and when U decide to share your truths, how do they receive those truths?

- What did U learn from that experience?

Another way of practicing surfacing distrust is the exercise that Malcolm suggested on my podcast: watching a YouTube video of someone sharing their perspectives on life and the world. Noticing if any distrust comes up. Validate it, and then try to notice that the person U are watching thought that what they are saying was worth saying.

Trust and Distrust Affirmations

Here are some affirmations I came up with, based on and inspired by the Non-Naive Trust Dance. U might find reflecting on these useful, or saying them aloud:

- I trust my own trust in myself.

- I trust my distrusts, the signal within them, and the choices I make based on them.

- I respect other people’s distrust.

- It’s okay to feel what I feel.

- It’s okay to know what I know.

- It’s okay to trust what I trust.

- It’s okay to distrust what I distrust.

- It’s okay for others to feel what they feel.

- It’s okay for others to know what they know.

- It’s okay for others to trust what they trust.

- It’s okay for others to distrust what they distrust.

- U can’t trust what U can’t trust.

- Just because X distrusts me, doesn’t mean I have to distrust myself in that way.

- Just because X trusts Y, doesn’t mean I have to trust Y in that way.

- Just because I trust X, doesn’t mean Y has to trust X

- Just because I trust X to A, doesn’t mean Y has to trust X to A.

- “Everyone is behaving sensibly even if I don’t yet understand why.” (Ivan Vendrov)

- Everything I think and feel makes sense, even if I don’t yet know why.

- Everything others think, feel, and do makes sense to them, even if I don’t yet understand why.

- I can tell how things seem to me.

- U can tell how things seem to U.

- My not trusting U does not mean U shouldn’t trust yourself.

- U and I are using different trust-systems, necessarily.

- I use my trust-system, and U use yours.

- I may distrust myself now in one respect, but I need not always.

Internal Trust Dancing

Malcolm’s Non-Naive Trust Dance applies at every scale—including within oneself, to our “parts.” Malcolm calls this “Internal Trust Dancing” (ITD).

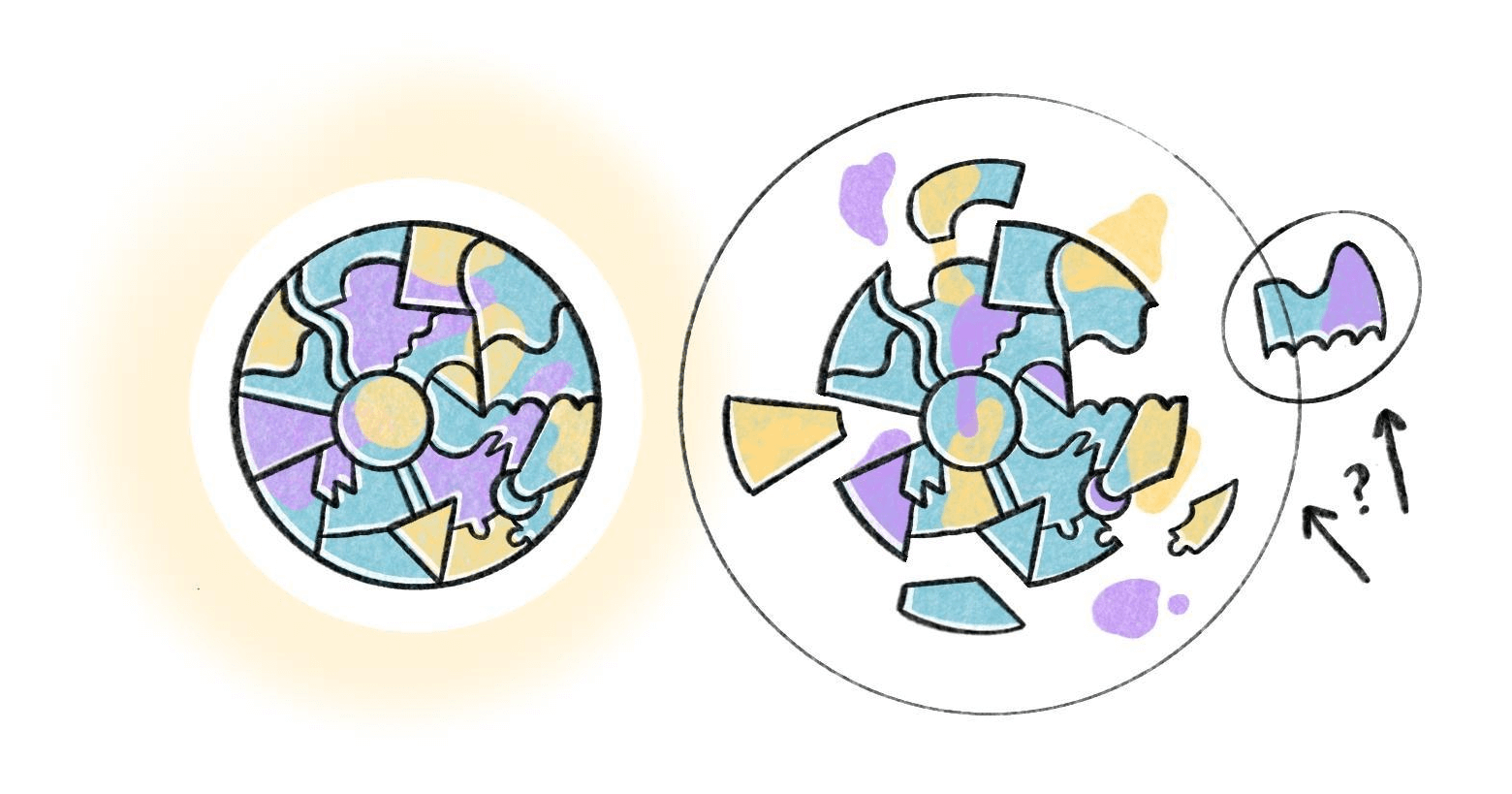

drawing by Sílvia Bastos, commissioned by Malcolm for Mindset Choice is a Confusion

ITD is analogous to Internal Family Systems and other partswork modalities, especially Coherence Therapy. Malcolm’s sense of Internal Trust Dancing is especially influenced by Perceptual Control Theory (PCT), which “was developed to model not just what’s going on when things break down due to trauma or unmet developmental needs, but also how things work when they work.” From a PCT perspective, parts can be “very tiny” and also “ephemeral.”

Malcolm notes that, unlike IFS, ITD doesn’t require reifying or naming the parts. Instead it “focuses on directly evoking or generating inter-part curiosity, perspective-taking, and empathy,” knowing that “from a given part’s perspective, what it’s doing makes perfect sense.” That includes acknowledging and respecting inter-part distrust.

For example:

- Part A of Joe trusts Part B of Joe to X.

- Part B of Joe distrusts Part A of Joe to Y.

- Parts of Joe trust Sadie to X.

- Parts of Joe don’t trust Sadie to X.

- Both parts of Joe trust Sadie to Y.

Malcolm’s practice of ITD also takes extensive inspiration from the Coherence Therapy modality, as presented in Ecker et. al’s Unlocking the Emotional Brain. Doing ITD, adopting a coherence perspective on parts work, can look like many different behaviors or moves, but it can include asking questions like:

- “What was it like when U [did behavior] X… what did it feel like, when U were in the headspace where it made sense to X?”

- “From that place, in that mode, how did U feel towards the part of U that [did behavior] Y?”

- “What does it feel like, right now, from your current vantage point?”

- “Does it feel true for that part to say to the other part…I don’t want U to feel… I’m not trying to make U feel…?”

Being able to apply trust dancing within one’s own heart and mind is good practice for—and sometimes a necessary precondition for—being able to do those same trust dancing moves with others.

Malcolm has several detailed posts—case studies—about Internal Trust Dancing, if U want to see what NNTD-flavored partswork looks like in practice:

- ITD case study 1: EA & relaxation

- ITD case study 2: scheduling & cancelling dates

- ITD case study 3: easy but impossible; welcoming suspicion

External Trust Dancing

Conversely, importantly, trust dancing also applies to navigating interpersonal situations with others, whether they are individuals or groups.

Malcolm laments that an enormous amount of human conversation and coordination “is conducted in a way that is saying ‘No, you don’t get to have your reality.’”

Instead, with NNTD, we get to say “You can have your reality. It’s different than mine, and you can have it… I’ve got a different reality, but also I respect that you have yours.”

Malcolm says that having had the NNTD insight has dramatically improved his ability to navigate conflict and “everyday apology situations”

I was able to approach a conversation where I knew someone was upset with me, and very easily listen to their perspective, empathize & reflect the validity of their concerns, without taking on a blame narrative, and end the conversation with them feeling very connected, appreciative, seen, etc. And all of that flows naturally from me grokking the principles of trust implied by the NNTD frame—I’m not doing any particular technique or form, I just literally show up and non-do a very satisfying reconciliation with zero effort.

I’ve long been fairly charming and good at defusing conflicts, but these experiences felt very different.

The other person doesn’t need to understand NNTD, or speak in NVC terms, or have experience circling, or have done a lot of IFS or parts work. Someone can apply it without expecting someone else to understand or follow suit:

The fact that it does interoperate with people who aren’t doing anything meta or frameworky or “collaborative” or “noncoercive” or “postblame” or whatever, is HUGE. And was a huge part of the whole point of the NNTD (as contrasted with a more dualistic conception of a cultural operating system shift) is that it wants to be backwards compatible to the extent possible.

The next few sections discuss specific NNTD-inspired moves we might deploy in practice when navigating trust and distrust with another person or group.

Naming Trust and Distrust

As U refine your own sensibilities for what you trust and distrust, U may choose to voice these statements in social, interpersonal settings that U find yourself in, care about.

Note that in many social environments, people don’t often explicitly name or even consciously notice trust dynamics, so it can be shocking or alarming for others if U do name distrust. This is true even if the degree or kind of distrust itself is moderate or banal or relatively inconsequential.

Respecting Trust and Distrust

Sometimes, someone will explicitly name that they have a distrust: “I don’t trust U” or “I don’t trust U to…” Or maybe they express a similar sentiment without using the word trust: “U seem like U’re just trying to…”

Simply acknowledging and validating this distrust can be incredibly powerful: “That makes sense that you can’t trust me! I’m glad U said that and I don’t want you to pretend that U do, or to force yourself to.”

Doing so builds what Malcolm refers to as meta-trust. I would describe that meta-trust as: there may be specific distrust about something particular, but there’s increased trust that we can navigate our distrusts workably enough for what we’re doing.

Verbally acknowledging and respecting that distrust may not be sufficient, and it may not be necessary. U may need to act in a way that demonstrates your respect for their distrust, or that builds trust. But it can be an important starting point, a useful move to have available.

Feeling Distrusted

Relating to others’ distrust of U can be uncomfortable! It can also be uncomfortable to notice your own distrust of yourself.

For me, I’ve noticed that I can feel a whole suite of feelings associated with distrust, including fear, anger, nausea, disorientation, and even disgust. In my experience, these feelings can be really intense and uncomfortable.

That said, I’ve started to really notice, respect, and pay close attention to when these feelings arise, despite their discomfort. There’s a lot of signal there!

To my mind, that signal is saying something like: “Wow, I’m starting to notice information that is disconfirming of my prior assumptions and worldviews, which I have habitually, subconsciously occluded before now, because it previously wasn’t safe to acknowledge or integrate these facts about reality—but now there must be a reckoning, lest I suffer.”

I asked Malcolm about how to work with these intense feelings of discomfort upon noticing others’ distrust of us, or our distrust of ourselves. He suggested that it can help to spend time validating your own trust for yourself.

Say, for example, someone distrusts that I am telling the truth. It can be uncomfortable to sit with that, to acknowledge that. And yet: they do distrust me! That is simply true. I would be foolish to ignore that information, this part of reality.

But that doesn’t mean I have to overwhelm myself by feeling bad. In this case, I do trust myself. I’ve taken the Fourth Precept! I practice honesty, not lying! I trust myself to not lie. Someone else may not trust my honesty, but I do.

Reconnecting to that self-trust can help create spaciousness around others’ distrust for us. Validating my own trust makes it more bearable to sit with that distrust.

Similarly, I’ve found it helpful to remind myself that I don’t need to adopt other people’s models of me wholesale. Their models are for them; my model of me is for me.

Say the Obvious

Sometimes, something is obvious to U, but not to someone else. If there’s ever a feeling like, “this should be obvious, and I shouldn’t have to say this, but…”—that may be a signal that that is in fact the perfect thing to say!

Here’s a simple example. Imagine U have a guest in your home. Let’s call them Jordan. They’re an old friend but it’s your first time hosting them. Something strange and unexpected happens in conversation. The vibes are off, but U don’t quite understand why.

As U listen to them talk about their behavior and needs, U find yourself thinking… “I’m pretty sure this is obvious… but maybe I should say it…” U decide to go for it: “U know, Jordan—U are welcome in my home. U are my guest!”

U see them relax visibly. Their muscles loosen, and they put their feet up on an ottoman. They had been feeling alien, foreign—like a stranger. But now they feel welcome in your home: safe to make themselves feel comfortable.

U two proceed to have an honest conversation about something they need to feel safe, and work to find something that works for both of U. And U then proceed to have a lovely, lovely visit together, that brings U closer and helps you to deepen your friendship.

Obviousness isn’t objective, actually—no matter how clear or straightforward something seems to us. “Sometimes things need to be said even though they feel like they really really should go without saying”!

Just because it’s obvious to U, doesn’t mean it’s obvious to someone else. “Different things are obvious to different people”!

Say the obvious! Try saying it anyway! Say it even if U’ve said it before!

Some Real World Examples

One of the tricky parts about learning NNTD is that it benefits from hearing and seeing concrete examples of its application—yet situations involving trust and distrust in an impactful way are often very private.

Some of the juiciest, most illustrative, and meaningful examples in my own life are ones I don’t feel comfortable sharing publicly. They’re either vulnerable personally or would violate someone’s privacy—or both.

Still, I’ve come up with a collection of real world, albeit anonymized, examples that I do feel comfortable sharing, to help U begin to understand the ways in which NNTD can influence the way we relate to others and our lives.

“I Trust U”

I was interested in working with a coach. I had an exploratory call to talk about the possibility of doing their program. As I mentioned some thoughts, questions, and concerns, they said several times: “I trust U.”

I noticed that this brought up a sense of distrust. What did they mean, exactly? I asked them to clarify what they trusted me to do. They answered with some specifics, and that met my sense of distrust. It wasn’t a generalized, naive trust. They were just speaking plainly.

Coaching Fit—or the lack thereof

For a nice counter-example: I was interested in receiving some coaching, in a different domain entirely. I found a service that looked interesting and like it could meet some of my goals. I heard some friends speaking highly of their work, so that was a good sign.

I scheduled an intro call with them. When I got on the call, something felt off. I didn’t quite like or trust their vibe, for no particular reason I could verbally explain. It wasn’t malicious, it just felt like we wouldn’t fit or work well together.

Still, I had the call. Maybe my intuitions were off. They had a number of onboarding questions, in the event that we did work together. I liked their questions, but I didn’t like the way the call was held, exactly. It didn’t feel completely attuned to me.

They made a pitch for their service, with a presentation. Then I asked some questions myself. It seemed like they offered about 8 services: 4 of which I needed, 4 of which I didn’t, and it was missing several that I wanted and needed. I also felt like their mode of working, and some of the specific things they would need me to do, wouldn’t work for me for various psychological and practical reasons.

I trusted them to be good at the services that they said they would offer, to be ethical and responsible and competent at what they explicitly offer publicly, but I didn’t trust them to meet all my needs or help me meet all my goals, or to do so in a way that felt good for me personally.

Given that, it didn’t feel worth paying them to help me with just part of my goals. By the end of the call, I decided not to work with this coach or their service.

I indicated as much on the call. In the days that followed, they proceeded to email and text me to follow up to see when I would sign their contract. More evidence of not being attuned, despite being competent!

Houseguests

I’m currently staying in a group house. As someone with a lot of friends and a large social network, I’m noticing that I’m interested in having lots of friends over, for dinner or to stay the night or a week. My housemates like meeting new people, but having people stay over—especially for several nights—is a big ask.

They’re rightly wondering, “Can I trust this person? Will having them in the house contribute to my life, or make my experience of living in my home worse in some unexpected way?”

Malcolm has this saying: “trust is only as transitive as it is.”

If I assumed trust was transitive, I might be confused that my housemates don’t trust my friends, who I trust and want to stay over. That might imply that they don’t trust me. That, in turn, would make me upset. That upset might cause me to consciously or subconsciously manipulate them into acting differently—trust wrestling.

I can remember situations where I felt that way in the past: upset that someone X didn’t trust someone Y that I trusted completely. But if I account for trust not being intrinsically, simply transitive, I can create a translation layer—a dance—between my trust and their distrust. Just because I trust Y to A doesn’t necessarily mean X should trust Y in the same way.

I can, for example, vouch for my friend. I can say I trust them, that I am confident there will not be negative impacts from them staying there. If there were, I would take personal responsibility for those impacts. I would also put my current reputation in recommending people on the line. If there were to be major problems, I should be disallowed to recommend people in the future.

I’m confident that if I did that, I wouldn’t have any problems. My friends are respectful, kind, responsible, conscientious people. Good houseguests, good company. All the more so if I indicate to them, “hey, my reputation is on the line here—please be on your best behavior as you navigate living in a group house for a few days.”

Vouching for a friend can create more trust while not overriding distrust.

Mating Dance

As most of my friends know, I’m looking for a wife.

Malcolm’s post “7 takes on falling sanely in love” may be especially useful and practical for anyone seeking love. It applies NNTD to the search for a life partner.

The fourth take in Malcolm’s post is “Everyone has a mating dance: respect yours & theirs.”

A mating dance is “the set of experiences [someone has] to go through with someone [else] in order to experience that other person feeling like a mate for them…they have different orderings for different people and cultures.”

U have to not only know your own dance, but guess at, discover, and be surprised by, interact with someone else’s dance. And your dances may ultimately be incompatible, which is important to discover, because it implies that U would not be good, safe, sane life partners!

I recently reflected on my own mating dance quite extensively. Malcolm provides about fifteen suggestions in his post, of steps that might go into one’s mating dance, ranging from “a first kiss” to “seeing each others’ finances.”

As I made a list, and ordered it, and reflected, I found myself with… more than 150 steps. The more I thought about it, the more my own sense of my mating dance became increasingly intricate.

And boy, have I skipped steps in the past. We out here learnin’ in samsara!

Importantly, a list like this is not a checklist. It’s not a standard operating procedure. U can’t proceduralize intimacy.

But it is an honest accounting of what U yourself need to be ready to partner with someone. And knowing that someone else has their own mating dance can help U attune to theirs, start to take steps in their direction, and iteratively co-discover whether that feels good and resonant and aligned—or not.

Conclusion

Think back to the situations about trust that U summoned at the beginning of this post: the ones that are on your heart and mind, that involve trust and distrust. Do U think about those situations in the same way, or see them in a new light? What’s changed?

For myself, NNTD has worked its way into my thinking and orientation towards every social situation that involves trust and distrust. I just can’t unsee what I see.

I hope that this blog post has helped make NNTD understandable and legible to U—what it is, why it matters, and how to start applying it in your own life and contexts.

I hope U are able to understand NNTD truly and deeply, on your own terms and in your own words, in a way that helps you to navigate social reality with grace and kindness, curiosity and openness.

I hope U are able to apply it practically, such that U can use it in all social situations U face, respecting your own trust and distrust, respecting other people’s trust and distrust. I hope that— in Malcolm’s words and metta phrase—it helps U to live a vibrant life on your own terms.

Further Resources

- NNTD Website

- Michael Smith’s Plain-English NNTD Summary

- Malcolm’s NNTD Videos Playlist

- How to Gently Blindly Touch the Elephant In the Room Together (or, how to give feedback to somebody about something that you’re noticing going on for them [and you], where you suspect that if you try to even mention it they’ll get defensive/evasive & deny it)

I am very grateful to Malcolm Ocean and Michael Smith for their support in the creation of this post. They very patiently explained NNTD to me repeatedly in verbal conversations and asynchronous correspondence for many months while I researched and wrote this post. They also accommodated my very specific and idiosyncratic requests for how I wanted to learn about NNTD—which, to my mind, is itself a very specific and precious demonstration of these ideas. And they were very generous in providing comments and feedback on multiple revisions of this post.

Special thanks to Ivan Vendrov for his financial support in the creation of this post. Thank U also to all my patrons who support my work in general.

Much gratitude to Sílvia Bastos, for her permission to reuse and adapt some of the NNTD-specific art she made for Malcolm.

Thank U to Andrew Conner, Eric Chisholm, Ellen König, Zencephalon, and Evelyn for their detailed and considered comments on drafts of this piece.