There is an online community that I’m in that has an unusual but powerful social technology for asynchronous communication, colloquially called “feeds,” inspired by old-school Facebook walls and RSS feeds.

This community has nearly 100 people, approximately 40% of whom are active on a day-to-day, week-to-week basis.

Most (but not all) communication in this community takes place asynchronously, using Slack channels and direct messages to communicate by text.

While most communities I’ve been a part of have a stable, small number of channels (typically 1-30), this community is notable for the abundant and prolific use of channels. There is no reason to constrain how many channels exist, so users are encouraged to create public or private channels on demand for any number of needs. Users are welcome to join and leave any channel as desired.

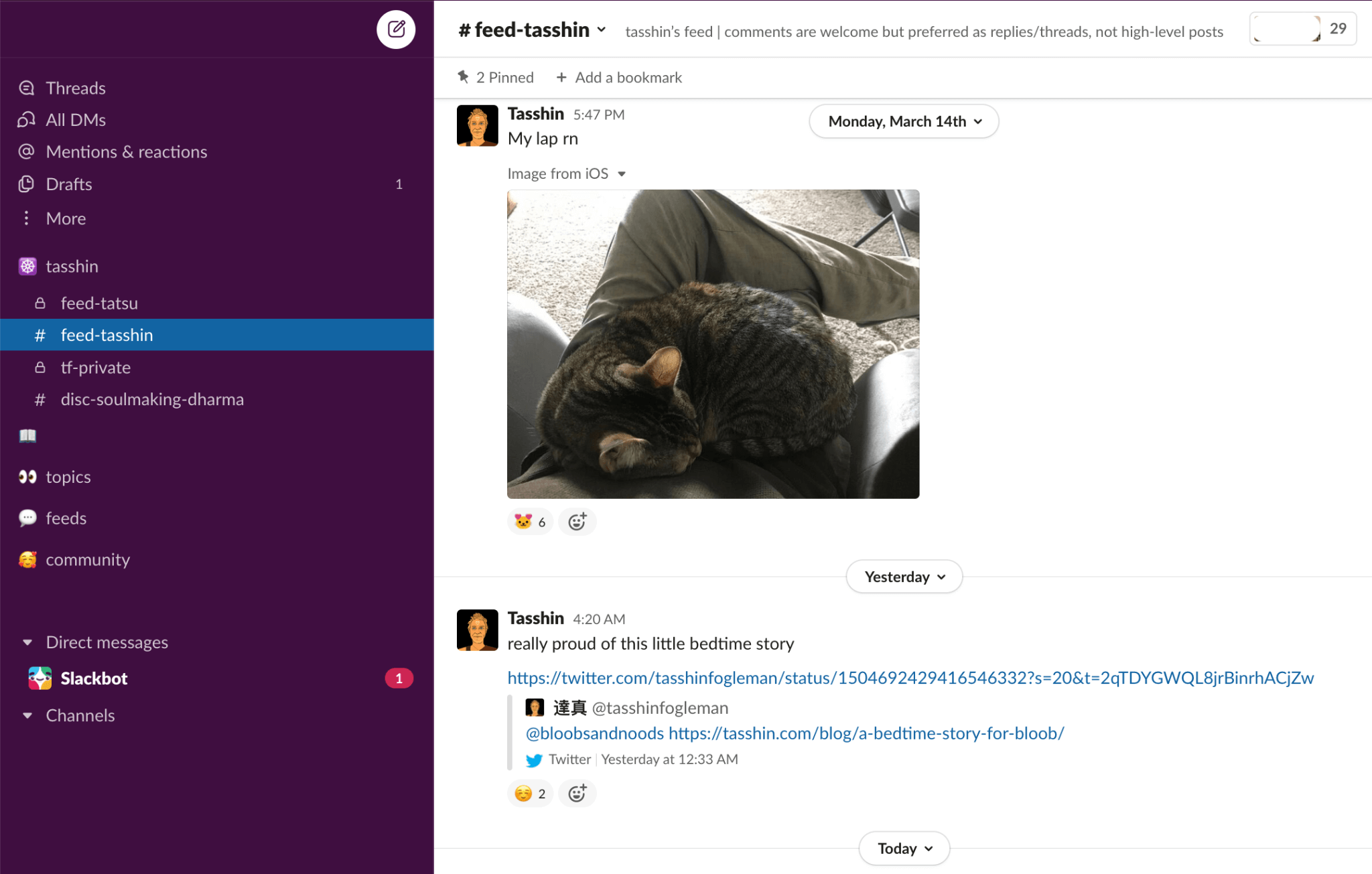

A common use for these channels are “feeds” for each person – e.g. #feed-tasshin, where I might post reports about my life that might be relevant or interesting for the larger group. People can respond or interact as they like, providing encouraging support or discerning advice.

People also commonly have private feeds that share more intimate details and reflections with a subsection of the community made up of close, trusted friends. Whether these personal feeds are public or private, they create a kind of social journaling that allows for personal introspection as well as support and reflections from others.

These personal feeds could also be tailored to a specific topic, e.g. #feed-tasshin-writing, #feed-tasshin-drawing, or #feed-tasshin-dreams. Whatever the topic or content, the person whose feed it is has power over that channel, in terms of deciding who to invites, what the norms are, etc.

Channels are also created for specific topics of shared interest, e.g. #disc-meditation or #disc-video-games. These are spaces for relevant discussion, links, questions, requests for advice, reflections, etc.

Users create a feed for each person, or topic that feels alive. These conversations can happen synchronously or asynchronously between as many people as are relevant or interested. Users can create, join, leave, archive, or group their channels as they like.

The culture encourages the abundant use of react emojis to participate in conversations, even if you don’t say anything to add to the conversation. Using reactions constitutes a form of reply game.

This community uses Slack’s premium features, with special reliance on full-history access, the ability to make custom channel groupings, and custom emoji uploads.

Asynchronous Community Culture

Overall, this community gives a sense of tremendous intimacy despite being primarily asynchronous. Of course, people are free to meet in person, do Zoom calls, etc., but the shared community culture is primarily asynchronous.

Over weeks, months, and years of reading each other’s feeds, you get a sense of who someone is very deeply, develop a love and affection for each other, and build a shared sense of intimacy in community.

The closest thing that I have personally felt elsewhere is the “dark timeline” on Twitter (see my Guide to Twitter), which is similar—but in my experience you can’t consistently go as deep on Twitter as is possible in this community, if only because of the limitations with Twitter threading. There’s also an advantage that comes from having a clear container for community, whereas the dark timeline is made up of a web of opt-in, one-to-one relationships that sometimes but not always connect into a larger community.

Many, but not all, of the members of this community (and the others that I’ve used it in) are extensive users of Twitter. This private community provides a safe haven from some of the problems of public Twitter use: bad replies, being ratioed or main charactered, etc. People can feel comfortable being more casual and relaxed, a sense of being amongst friends, that isn’t possible on the public timeline.

Users also often crosspost wisdom that they’ve discerned from their private reflections and conversations into a public venue. I’ve personally come to value this kind of abstraction:

17. where possible, it’s good to — carefully, skillfully — abstract and crosspost private insights from journals or conversations more publicly as much as possible so that as many people can benefit as much as possible. we all have wisdom the world needs.

— 達真 (@tasshinfogleman) March 19, 2022

Primarily asynchronous communications between online people who are geographically distributed has noted downsides. People can know and love each other deeply, but be limited in their ability or willingness to provide a host of forms of practical support that would be normal and expected in local, in-person relationships and communities.

This can be compensated for to some degree by private phone calls and text messages, group Zoom calls, local meetups, and other collaborative efforts.

In particular, I think the Microsolidarity Framework is an especially powerful complement to these feeds. Microsolidarity excels at building community through live, synchronous crew meetings (online or in-person), while these “feeds” excel at building community and shared context through asynchronous communication tools.

I feel that Microsolidarity practitioners could benefit from considering adopting these “feeds” in their communities, and that communities using these feeds could benefit from adopting synchronous, Microsolidarity-style crew meetings.

Implementing Feeds In Other Tools

Similar configurations are also possible in Discord or other similar applications. I’ve personally adapted the use of feeds from this community to another community I’m in in Discord, as have others. See A Guide to Actually Enjoying Discord.

Discord has some advantages. First, every server has full search history access, regardless of whether they are paid or not.

Second, users on Discord can message each other privately even if they are not in the same communities, allowing relationships to develop (and messages to be searched) even if someone leaves a particular server, or that server closes.

It also has some disadvantages. One major disadvantage is that the server owner is automatically added to all private channels, so there is no real privacy for users who might want to create a channel that is just for them or a few select friends. It’s possible to approximate this if the server administrator mutes the channel, but that requires a shared sense of trust that may or may not be present and cannot be assumed.

Overall, I’ve found Discord’s threading system is not as strong as Slack’s. Discord also doesn’t allow custom channel groupings.

With Discord, it’s also impossible to sign in to one specific Discord without being logged in to others, which you can do in Slack. This can produce a sense of information overload, context blurring, and a feeling of overwhelm.

This could be implemented in any community discussion tool that works like IRC, Slack, or Discord, with chatrooms / channels. Other functionality that would support these use cases seems possible. In particular, Zulip’s threading model seems especially interesting to me personally, although it is not as well known or as widely used as Slack or Discord.

Conclusion

In general, if a community could benefit from more shared intimacy, and social journaling, introspection, and conversation, then these feeds could be a relevant and useful social technology.

As the internet grows and evolves, a wider variety of social technologies and cultures will grow and adapt. Documenting these practices and social technologies anthropologically, and experimenting with them practically in the communities you care about, is a valuable practice for your local communities and the broader ecosystem of human culture in a global, online world.