In this post, I’ll show you you how I might apply Empire Theory and Burja Mapping to a more or less “real world situation.” I have so far typically applied these tools to situations related to my work at the monastery. Those situations are not the best for demonstration purposes, since they are somewhat idiosyncratic and also private. So I thought it would be fun to apply the tools to a more familiar setting, through film. Let’s look at the film Moneyball (2011), based on Michael Lewis’ best selling book.

Moneyball is a great example for us to work with. While the surface plot is concerned with something very specific — the use of statistics in baseball (sabermetrics) at the Oakland Athletics — the dramatic elements come from the power dynamics at play.

Here’s the basic plot of the movie, for those who might not have seen the movie. (Warning: spoilers ahead.)

The year is 2001. Billy Beane is the General Manager of the Oakland Athletics. The A’s are a relatively poor team, and have just lost in the post-season to the big-budget New York Yankees. Billy meets Peter “Pete” Brand, a recent Yale graduate working a desk job at the Cleveland Indians. Billy notices that during his negotiations with the Indians’ GM, the Indians’ GM seeks out and takes Pete’s advice regarding their deals. Billy is surprised — he had proposed a good deal, which a low-level person he doesn’t know has the power to cancel.

Billy meets privately with Pete and finds out that Pete has been inspired by Bill James and sabermetrics. Pete, a huge baseball fan, thinks statistics could completely reshape baseball. Billy poaches Pete from the Indians, and they set out to rebuild the Oakland Athletics around Pete’s ideas. Despite some obstacles and a limited budget, the new team accomplishes stunning, unprecedented successes.

The Scenario

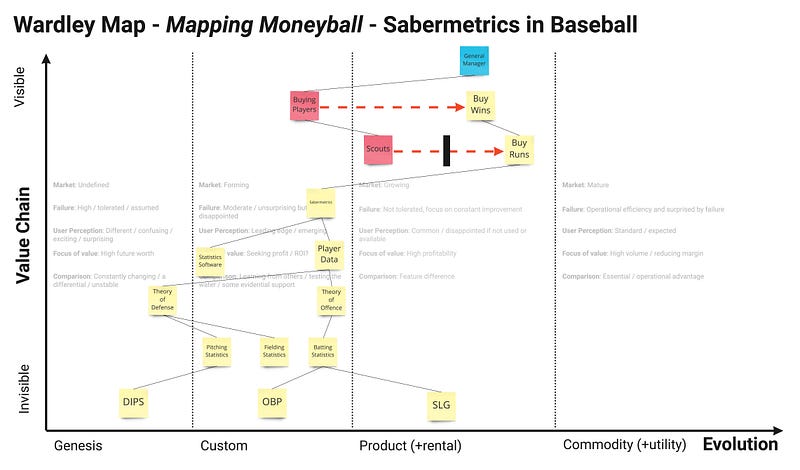

Now, imagine you were Billy Beane, desperate for a way to beat the Yankees and the Sox, seeking answers. You might be inspired to make a Wardley Map of baseball. Or, after meeting Pete Brand, you might make a Wardley Map of sabermetrics — or even a maturity map.

Undoubtedly, those maps would produce valuable insights, and potent gameplay.

However, as we see in the movie, it’s pretty obvious early on what Billy Beane should do. He knows to hire Pete Brand, and give him autonomy and power over certain aspects of decision making, especially scouting for and acquiring new talent. Billy’s ample experience with baseball in general, and managing the A’s in particular, gives him the skill to make various negotiations and adjustments as needed throughout the film.

Where he runs into trouble, however, is in dealing with the people. Billy and Pete are introducing a new paradigm not only to the Oakland Athletics, but to baseball in general. They encounter several forms of inertia both internally and externally, and have mixed success at dealing with that inertia. They might have used their Wardley maps and strategic thinking to anticipate that. Wardley’s framework provides useful information for orientation and decision. Figure 129 in his book helps identify which form of inertia one is facing, and what tactics or gameplay might help address that inertia. They might also have made Burja maps of their landscape, instead of or in addition to this more typical strategic exercise. Let’s illustrate the kinds of Burja Maps Billy might have made.

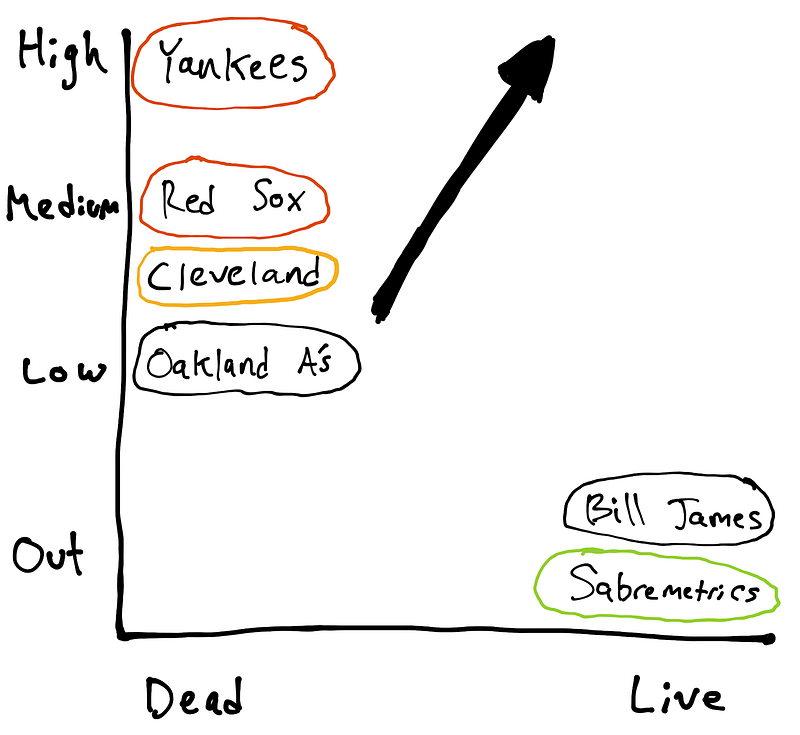

First, the big picture, baseball in general. There are many people, teams, and organizations inside and outside of baseball as a whole. This Burja map demonstrates the relevant empires within the American League in the film:

The domain of competition is the league’s pool of baseball players. Selecting the right set of skilled players will result in a championship team; picking the wrong players will result in losing.

The Yankees (ALDS Champs of 2001), with the largest budget, are the most likely to draft high-demand players. The other prominent teams featured in the film include the Red Sox (still hoping to break that curse), the Cleveland Indians, and the Oakland A’s. The other teams are all competing against the Oakland A’s, but Billy negotiates from time to time with all of them for baseball talent, especially the Cleveland Indians.

All these players are dead — following the script, using the same stuck definition of what a good player is. Bill James (the person) and the practice of sabermetrics (a resource) are live but out. Billy, our hero and the Oakland GM, will align with the resource of sabermetrics to make a play to increase overall power and vitality.

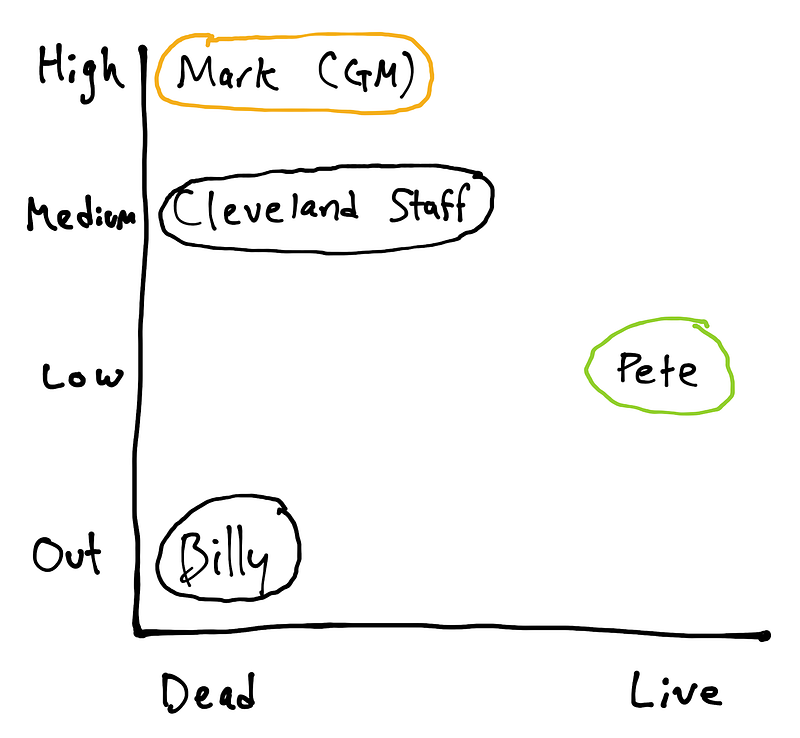

Second, before and during his business trip to Cleveland, Billy might have made a Burja map of the Cleveland Indians, where he is an outside player. Even though Billy doesn’t have a formal org chart of the Indians, it would be easy for him to get a working map. Mark Shapiro, Cleveland’s GM, seated at the desk, is obviously the high level person — the person he came there to see and make deals with.

Billy and Mark are peers, having the same position on separate teams, but Mark has more power over Billy because he has a bigger budget.

The men sitting in the back of the room are mid level players, the respected staff who work for Mark. Pete, standing, is the low level player:

However, when Mark indirectly seeks his advice out during the negotiation (through a mid level player, presumably Pete’s manager), Billy realizes he is a live player in Cleveland’s empire:

During or shortly after this meeting, Billy might have made the following map of Cleveland’s empire:

Here, the domain of competition is also player talent, but just the players whose contracts Cleveland (and Oakland, “Out”) control.

Billy picks Pete’s brain- why is Pete, a low player, live? Is he just someone’s nephew, or is he doing something new and powerful? After learning it’s the latter, that Pete has owned power in the form of statistics and sabermetrics, he, as out, decides to poach Pete. Billy’s main move here to is to try to align with Pete, a live player who can help him with his main goals. This is Billy’s best strategic gameplay in the film, and the basis for Oakland’s success.

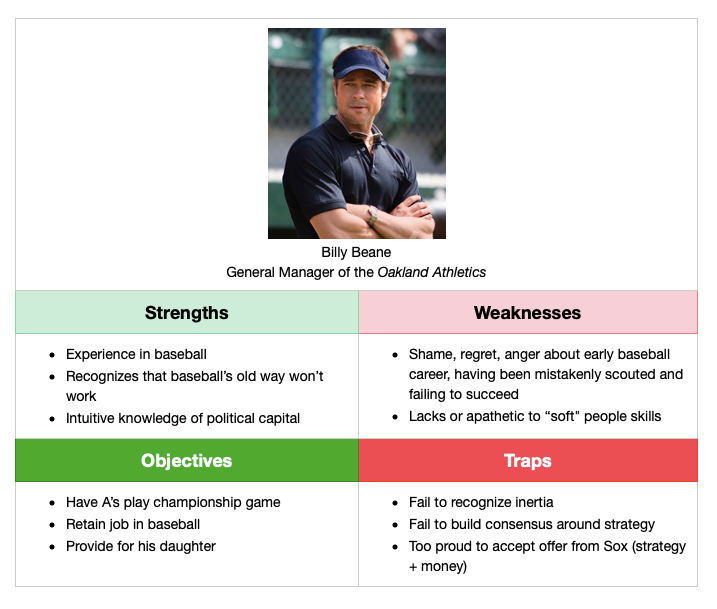

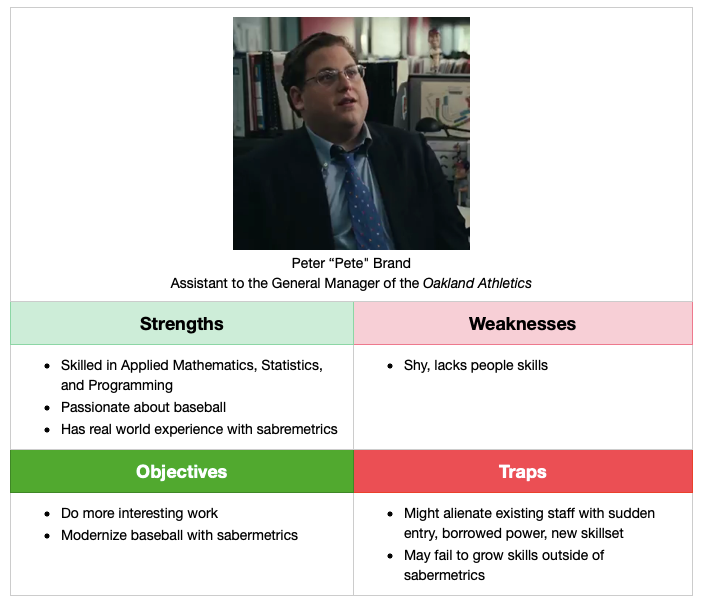

When considering a broad alliance with Pete, he might have made a SWOT diagram for each of them:

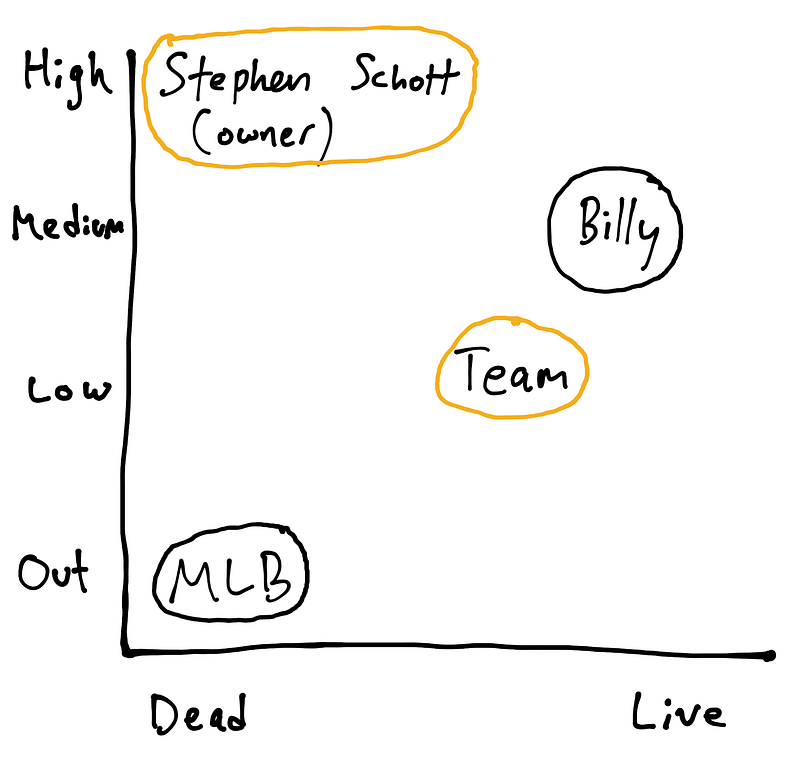

Billy might also have made a power map of the “high” power within the team, especially his relationship with the owner:

The empire is the Oakland A’s viewed at the highest level; the domain of competition is control over the team, especially money, as it relates to players and strategy.

Billy is a mid level player. He reports to Stephen Schott, the owner. Steve doesn’t want to give him more money, and asks him to make do with the budget he has. Steve and the team are ostensibly on Billy’s side, but Billy needs to be careful as he shifts from an old, dead paradigm (traditional scouting + management) to a new paradigm (applied sabermetrics). With the right gameplay, the team and the owner could be among his best allies; without it, Billy risks firing from above and mutiny from below.

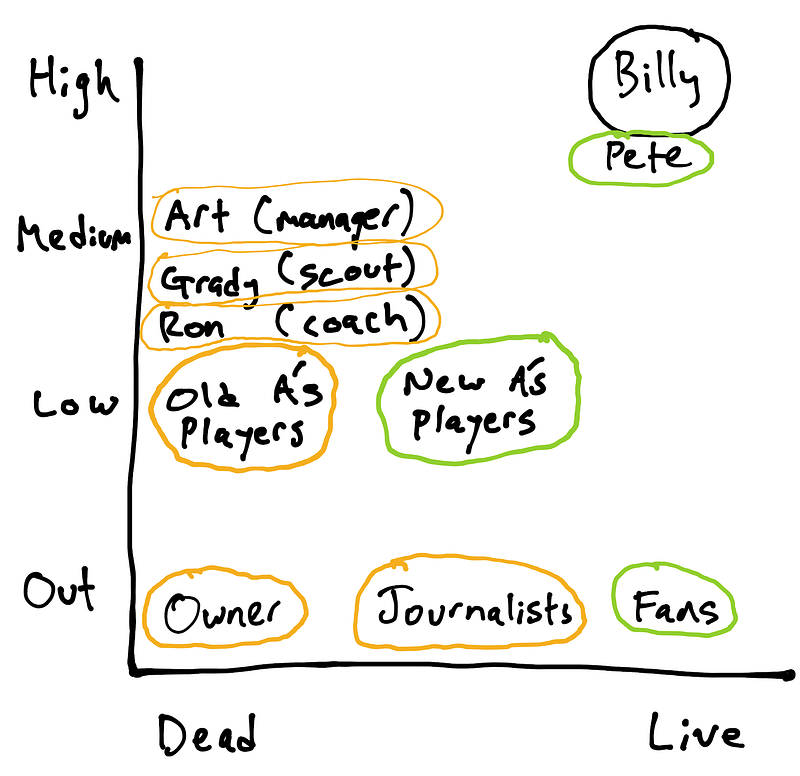

One final map holds much of the value Billy might have gained from creating Burja maps as he implemented his new strategic direction. This map would show those “below” Billy: his manager, scouts, and players. Here, it seems to me that the domain of competition is decision-making power as a symbol of status, respect, and skill.

Billy makes Pete his assistant, giving him borrowed power. They have a broad alliance, which Billy leans on throughout the film. They are no longer competing for resources (Cleveland vs. Oakland, traditional scouting vs. sabermetrics). Billy doesn’t need to worry about Pete rebelling against him or leaving him (at least for the time being). They make a good team.

Billy and Pete decide to recruit new players, in a narrow but strong alliance. The new players are generally overlooked by other teams (“an island of misfit toys”) and are grateful for the unexpected opportunity to play. They stand to benefit from Oakland’s use of sabermetrics, receiving more playtime, prestige, and money than they would otherwise.

While there are many fans, they are uncoordinated, and hold little real power over Billy. Moreover, they are likely to be sympathetic to improvements in Oakland’s management so long as those changes have real results (victories).

Beyond Pete, the new players, and the fans, pretty much everyone else is dead. In terms of alignment, almost all of the other players are also almost all neutral, a potential obstacle, or even enemies. Most importantly, most of baseball’s infrastructure — scouting, management, ownership, and even journalism — have little to gain, and much to lose, from the interventions that Billy and Pete put in place.

Given the sheer level of inertia, Billy might have anticipated that someone would revolt. In the film, he doesn’t seem to predict who will resist him, or how effective they’ll be, until later in the season. In the book, Lewis describes him having a little more clarity:

He couldn’t help but notice that his scouting department was the one part of his organization that most resembled the rest of baseball. From that it followed that it was most in need of change.

Regardless, he could have made plans to proactively prevent and manage inertia.

Instead, Billy did not sufficiently anticipate how inertia in baseball would affect power dynamics within the Oakland Athletics. He knew how to capitalize on inertia externally (hiring Pete, giving him power, scouting undervalued players) but was slow to account for internal inertia in his strategy. Billy charges full steam ahead, implementing sabermetrics at Oakland without regard for dead players in his empire.

Actually, Billy’s behavior is, at times, even worse than simply ignoring the dead players. He actively belittles them, implicitly equating “dead” with “stupid.” In his first meeting with the scouts, he uses aggressive body language to make his points. This is unkind and unnecessary.

In his second meeting with the scouts, he brings Pete into the meeting with little or no introduction before abruptly proposing a complete and total shift of their paradigm. In so doing, Billy decreases his old allies’ status, setting the scouts up to resent and oppose Pete and the implementation of sabermetrics. These and other, similar, examples of discourteousness lead him to have more impactful conflict with the dead players with less power than him, especially Grady Fuson and Art Howe.

Eventually, he learns his lesson, negotiating with David Justice. He correctly identifies David’s motivations and finds a win-win outcome. He could have used these same skills — and a touch of polite kindness — in his relationships with Art, Grady, and the other scouts.

With these maps in hand, Billy might have anticipated that inertia and obstruction. He might have found creative ways to proactively garner support and alliance from those who might otherwise oppose his efforts — or at least develop ways to minimize their obstruction and inertia.

He might have proactively and thoroughly brought those most prone to inertia on board ahead of time. This might look like explaining the how and why of specific choices. He would need to take into consideration not only how it benefits the whole team’s chances at a championship game, but also how it might benefit individual players.

For example, he could use some of his budget to give Art, Grady, Ron, and other key players a bonus, either at the beginning of the season as a sign of good faith, or as a promised carrot at the end of the season on the condition of cooperation.

Alternatively, he could have taken a more cold-hearted but potentially more effective approach, the one Michael Lewis describes J. P. Ricciardi, GM for the sabermetrically-enhanced Toronto Blue Jays, taking: “fire a lot of scouts, hire someone comfortable with statistical analysis…and begin to trade for value, ruthlessly.”

Of course, hindsight is 20/20, and the point of this post isn’t to pick on a semi-fictional Billy Beane. (As Lewis portrays him, Beane is both wiser to the points made here, and more flawed than Brad Pitt’s Beane.) Nor is it to prepare us for managing a baseball team. Instead, we’ve demonstrated the use of Empire Theory and Burja Mapping in combination with more familiar tools like SWOT diagrams and Wardley Maps. We’ve also learned some generally applicable lessons about power:

- Billy’s best move was to align with Pete. Pete’s owned power in the form of sabermetrics changes Billy’s career, the history of the Oakland Athletics, and baseball writ large. Align with live players where you can. A low, live player can change everything.

- Billy Beane poaches Pete in a parking lot and over the phone. If you are out with respect to an empire, and want to make a power play within that empire, seek neutral territory for negotiations.

- Billy experiences intense inertia + resistance within his organization. Even within organizations, there is competition. Just because you’re on the same team, doesn’t mean you’re on the same team.

- Inertia is a clue that you may find it useful to map empires and make power plays alongside more traditional strategic tools.

- Proactive power assessment can make you less likely to run into obstacles and more likely to succeed

- Live play requires a new paradigm (intuition -> statistics/economics; buying players -> buying runs)

- Being right and/or having a power doesn’t give you permission to be a jerk. Be kind to those in every empire, whether you are in or out, high or low, and you will navigate inertia and change more smoothly.

- Billy Beane declines the Red Sox offer. Arguably, this was a mistake. If you have the opportunity to implement the right strategy, with less inertia, and with ample resources (and a sizable raise), take the job.

If you enjoyed this post, you might enjoy reading my progressively-summarized notes of the book: Moneyball by Michael Lewis.