This post contains a new kind of strategic mapping, similar to Wardley Mapping, but concerned more with the complexity of human power dynamics. I am tentatively calling it Burja Mapping, or, if you prefer a less playful but more accurate name, Power Mapping.

I will review Samo Burja’s work on power and strategy, as well as Simon Wardley’s work on the importance of mapping. With that context, I will then show examples of Burja Mapping so that you can try it yourself and report back.

Who is Samo Burja?

Samo Burja is a sociologist and the founder of Bismarck Analysis, which analyzes institutions, from governments to companies. For our purposes, he is the author of a treatise on power and strategy, Great Founder Theory (original, notes). This treatise contains a cohesive, novel, and powerful perspective on power, which he defines as “the ability to realize your will, to affect the world in ways you desire, to achieve your goals.” It also includes important questions like, what drives social change? What are the origins of institutional health or sclerosis? Why has there never been an immortal human society? And: why was Barack Obama elected president in 2008?

Burja’s main concern in Great Founder Theory is advancing his eponymous theory, which revives “the great man paradigm.” According to Burja, Great Founders are “those who found the most functional institutions that contribute to the bedrock of their civilizations… Via the creation of institutions, Great Founders become the shaping force of society.” This includes not only powerful political leaders like Obama, but also entrepreneurs like Elon Musk.

For Burja, power is morally neutral. There may be rules, but you can bend or break them. Those options are open not only to you, but also to any other strategic actor, who might have less qualms about making amoral or immoral plays against you. Ultimately, though, the treatise encourages a higher, more cooperative form of power. The paper argues that the most effective plays are cooperative:

“The best way to win at adversarial encounters then, is to focus energy on building out cooperative ones. In the long run, acquiring power and empowering others is mutually reinforcing rather than mutually exclusive.”

In building out the case for Great Founder Theory theory, Burja advances another theory, Empire Theory, which will be the focus of this post.

What is Empire Theory?

Empire Theory is “a framework for understanding and practicing competitive strategy… [an empire is] a group of coordinated actors that operate around some central power.” Empires might be composed of players, resources, and other empires. Therefore, Empires are fractal: “there will be sub-empires within any given empire.”

In any empire, actors can be grouped into “power classes” based on their “relative power levels”:

- High is the central power that defines an empire’s zone of coordination. Without high, the empire would not exist and the other actors would not be coordinated. High also plays the largest role in determining the distribution of resources within the empire

- Mid is the collection of individuals or groups that have sufficient power to challenge high’s control. Mid players will often have smaller empires of their own.

- Low is the collection of players that can challenge mid but cannot challenge high. Low has the largest population and the least power.

- Outside is any actor that is not coordinated by the high power.

Here’s a typical example: there’s a company, in which there are various executives, managers, employees, and stockholders operating around a CEO. The CEO has a high power level. Executives have high or medium power level, while managers typically have medium power level. Other employees have low power level, and stockholders, competitors, journalists and other players are all “Outside” or “Out.” Because, power classes are also fractal, you could break out many of these entities into further empires or power classes, e.g. the “TPS Report team” might be low power.

Each player can also be considered to be live or dead: “A live player is a person or a tightly coordinated group of people that is able to do things they have not done before. A dead player is a person or a group of people that is working off a script, incapable of doing new things.” A CEO may be high power, but they may be simply doing the same thing they did at their previous company; or, a lowly employee may be receiving little to no pay, but they might be blazing new trails strategically and/or technologically.

With Empire Theory in hand, you are capable of assessing people and organizations in terms of power, as well as evaluating possible strategic plays.

On Mapping in Strategy

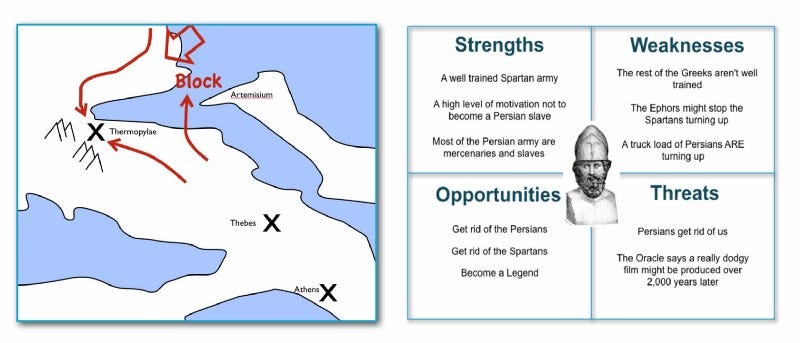

Simon Wardley has advanced the utility of creating a way of visually representing a strategic landscape. With maps, we can assess the status quo, make plans for the future, and learn from our successes and failures. Consider his humorous example: “what do you think would be more effective in combat — a strategy built upon an understanding of the landscape or a SWOT diagram?”

As a self-described “imposter CEO,” Simon realized that he was using the wrong tool in his business (SWOT’s and other similar tools) rather than a map, and set out to create a map or visual artifact that could accurately describe the territory he was facing.

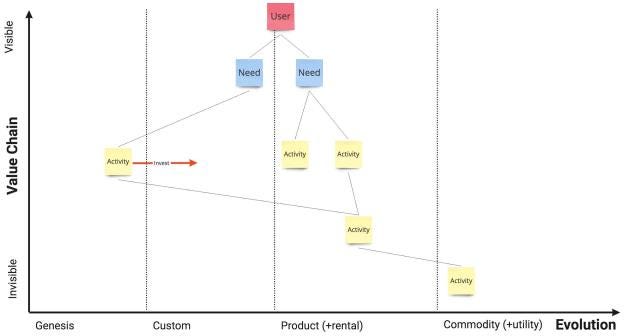

Simon created what is now called Wardley Mapping. Wardley Maps pair traditional value chain mapping (how do we meet the user’s needs?) with evolution (how evolved is the component?). As Ben Mosior describes it, this results in “a single, dense graphic describing our assumptions that anyone can learn to read”:

Wardley Maps have gone from the being the invention of one CEO to being increasingly used in business, government, and other domains (I use them at the monastery I train at). There’s even a conference. As Wardley mapping becomes more standardized and common, one area for further development is exploring alternate methods of mapping, with alternate axes.

In my view, Wardley maps are useful in a specific setting — what in the Cynefin framework is called the complicated domain. But people are complex, and all groups and organizations have people in them. Burja’s work presents an opportunity to find ways to visually represent power dynamics, using the same methodologies that Wardley pioneered: mapping.

Towards Burja Mapping

What follows are my initial efforts at synthesizing Burja’s frameworks for interpreting power, and Wardley’s maps. Again, I am calling these methods Burja Mapping or Power Mapping. Wardley mentions that his maps were iterative; these, too, are likely to change, and are subject to evolution.

Burja Mapping is useful for the subsection of the complex domain that involves humans, and, specifically power dynamics. It simplifies some of the power dynamics that are present in any any level of any human interaction. When we make those simplifications, certain standard (and non-standard) plays should become clear and available.

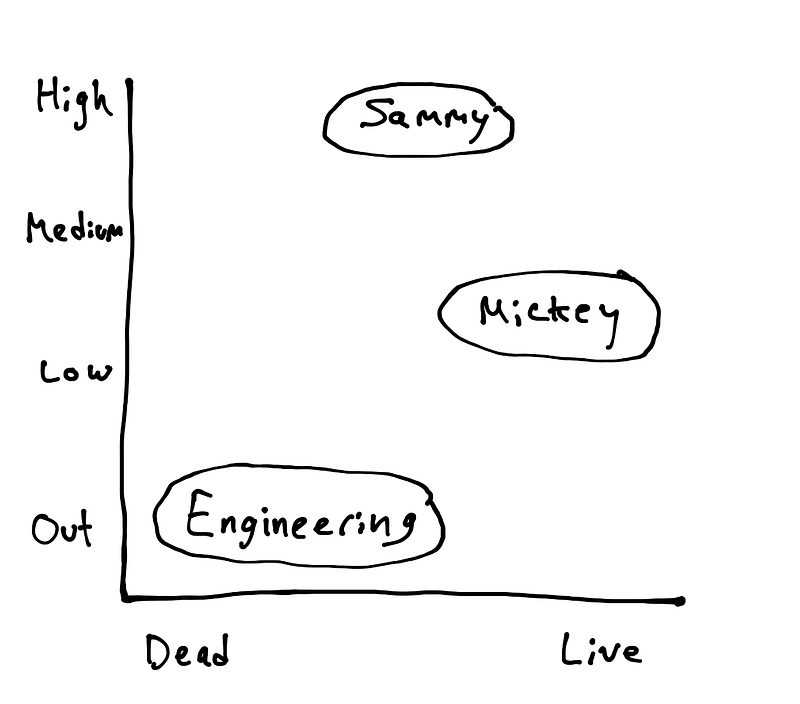

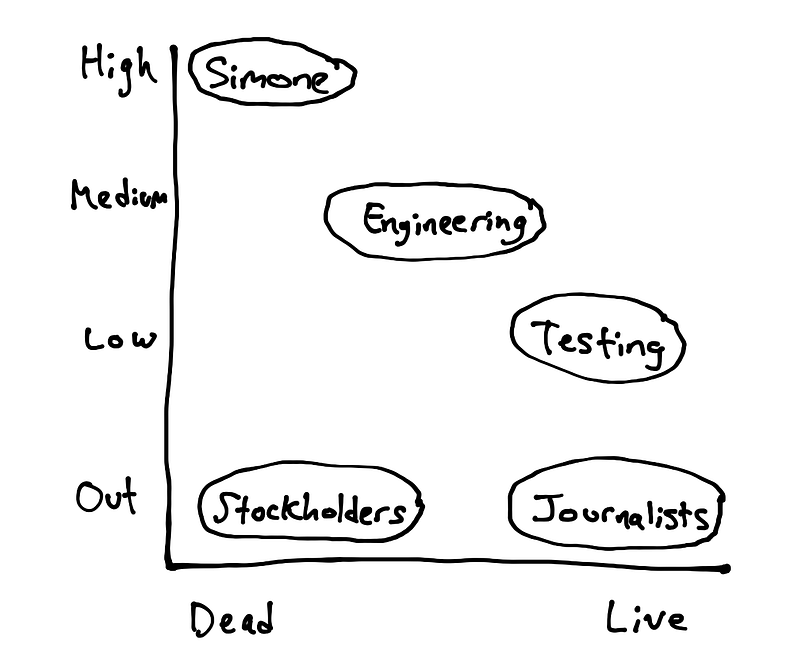

In Burja Mapping, the Y-Axis is Power: High, Medium, Low, and Out(side); the X-axis is Vitality: a player is dead or alive. The power class is likely to be a constant feature of Burja Maps, but I can imagine alternate x axes coming into play, e.g. money, programming skill, etc.

Let’s go through an example. You are Mickey, a lowly employee in SoftwareCo with big plans for advancement. You have a manager, Sammy, who runs the Testing Team. Sammy reports to her boss, Simone, who has suspiciously pointy hair and also runs the Engineering Team. Simone is also worried about stockholders, who keep selling their SFCO stocks, and journalists, who keep panning SoftwareCo. By and large, stockholders buy and sell SFCO based on what journalists say. The journalists keep finding new and innovative ways of researching what’s really happening inside SoftwareCo.

In this situation, we might make two Burja maps, one of the Testing Team, and one of SoftwareCo as a whole.

As fabricated as SoftwareCo and its employees are, this is a perfectly plausible situation. I’ve made maps of my whole organization at three levels, as well as maps of other people’s organizations, and a lot falls out. By mapping the situation, we gain an explicit sense of the status quo, and can also begin to plan strategic plays.

Because Burja Mapping is brand new, what those plays are largely in the “Genesis” category: unique, rare, uncertain, constantly changing, and newly-discovered. Burja’s paper shares a number of possible plays, and, as the practice of Burja Mapping spreads, more people will be able to report on the plays and patterns they’re discovering.

As with Wardley Mapping, I’ve come to the point where I can quickly make Burja Maps in my head, and make spot assessments and decisions. So far, I’ve primarily found them to be useful internally, in my own mind. This is because the contents of a Burja Map might not be something you want to share with others, not only to avoid competitive plays, but because sharing your read on the landscape might break certain rules of etiquette. It might not feel nice for someone to notice that they are perceived as low power, or as a dead player.

Conclusion

Burja Mapping isn’t a replacement for Wardley Mapping — it’s just a counterpart to it, a complementary view on the same kinds of questions and problems that everyone who is thinking strategically faces.

If you’re interested in learning more, here are some additional resources:

- Samo Burja’s Great Founder Theory and my notes

- Samo Burja’s blog, with excerpts from Great Founder Theory and other content

- A talk from Samo on Civilization: Institutions, Knowledge and the Future — Samo Burja — YouTube

- Ben Mosior’s Wardley Mapping Resources page

As you dive in, I’m curious to learn — would you make these power maps differently? How are you applying them? What plays are you discovering?

Subscribe to my newsletter, my YouTube channel, or follow me on Twitter to get updates on my new blog posts and current projects. You can also support my work and writing on Patreon.