As I’ve written elsewhere, there was a time in my life where I did a number of drugs. Nothing too hard, but I smoked marijuana and did psychedelics frequently.

Drug use opened my eyes to the possibility of altered states of consciousness. I realized that my experience need not be limited to either ordinary waking consciousness or sleep and dreaming, but that many other states and realms of consciousness existed. I found using drugs to be extremely pleasurable and enjoyable, and it gave me a sense of freedom from the challenges my school and social life presented me.

However, I eventually cooled to the drugs I had been taking. There were too many disadvantages to my taste. I had to pay money to purchase and ingest an illegal substance, that gave me access to pleasurable, altered states for a time, before it went away and I had to lie about my experiences to my parents and other authority figures.

I stopped taking them, and at about that time, I started meditating and found myself seeking a spiritual path. As George Harrison said in Martin Scorsese’s documentary, Living in the Material World, “So, at that point, I stopped taking it, actually, the dreaded Lysergic. That’s where I really went for the meditation.”

Many contemporary spiritual practitioners and teachers find their way to the spiritual path by way of drug use. That was certainly my experience. In retrospect, I think part of my motivation was to replace drugs with something more wholesome and sustainable. I wanted to find a way to reliably access pleasure and bliss, on demand, without any of the downsides drug use had for me.

It took me ten years, over fifty meditation retreats, and extensive monastic training to find out how to do so. But it’s possible, and it doesn’t need to take you as long, or require you to do monastic training, to find access to these benefits of meditation. That’s what this post is about.

Everyone has experienced bliss, joy, pleasure. A first kiss, a tender moment with a friend, graduating from college, receiving a promotion at work, or even through ingested substances. Life circumstances and substance-induced altered states have their joys and pleasures, their rewards and their delights. However, it is possible to self-induce these experiences of pleasure with meditative techniques, independently without depending on ephemeral circumstances or substances.

It is possible to learn to give yourself bliss, pleasure, joy, happiness, and fulfillment, at any time, on demand. It’s surprisingly easy. You shift what you pay attention to, and how – and suddenly you are in a state of bliss.

As far as I can tell, nearly everyone can learn this skill to some degree. The lighter forms of these bliss states are definitely possible for you to get into. It’s a long journey to master these states, but the skill is life-changing and highly worth the time and effort.

This article is about learning these bliss states, which are also called jhānas, concentration states, or samādhi.

What are bliss states?

The bliss states, or jhānas, are a series of concentration states. You can learn to enter these states through meditation techniques.

Jhānas feel great: they are extremely pleasurable, and very relaxing for the body and for the mind. They likely have psychological benefits, and are classically considered ideal if not necessary for the path to awakening.

Different people talk about jhāna differently, which can be very confusing. Here, we’re discussing what are sometimes referred to as the lighter jhānas or the “sutta jhānas.” These lighter jhānas are very real, relatively easy to get into, and truly life changing.

For now, know that different teachers and traditions may mean different things, and that there are deeper versions of these states. Above all, take the instructions here and elsewhere with a grain of salt. Put your own experience at the center, rather than putting someone else’s words first.

The jhānas are the natural direction the mind wants to go.”

– Ayya Khema

How do I enter bliss states?

To begin, be sure you’re familiar with the Five Hindrances. You cannot enter a bliss state if you are in a hindrance, so cutting through them in a given meditation session is necessary.

Once you have cut through the hindrances, you can use any meditation technique to enter a bliss state. The most common techniques used to enter bliss states are following the breath, doing body scans, and doing loving kindness meditation – but any technique can work.

The instructions are simple: do a technique you are familiar with, and attend to the relevant focus space. If and when it starts to be enjoyable in the body, and the enjoyment is stable, then you shift your focus space to this pleasure and enjoyment in the body.

To put it very simply: do a technique that feels good, and then enjoy it. Really enjoy it.

Although there are many roads to entering bliss states, I’ve found that in practice, loving kindness meditation is one of the most direct. This is because for most people – by my estimates, roughly four out of five people – loving kindness feels or can feel really good.

For some people, perhaps if they’ve had a significant amount of trauma, loving kindness can be painful or challenging. This is very normal, and that just means that taking a different road to these bliss states might be easier, at least to start.

Still, loving kindness is a good default for a lot of people, and if it feels good, then that’s a tried and true way to get into these states.

Standing meditation, or Zhan Zhuang, is a valuable complementary practice. A daily standing practice, starting with five minutes, working up to at least twenty minutes, will help you to charge the energy body. It will be easier to notice and enter these bliss states if you have high amounts of energy in the body.

If you do these two things frequently, loving kindness practice and standing meditation, then you’re going to feel increasingly good. You’re going to feel relaxed physically, you’ll be increasing the amount of energy in your body, and you’re going to feel happy emotionally.

Take this direction and explore it for yourself. Just try the instructions, and experiment. See what happens!

Attention and Awareness

Understanding the distinction between attention and awareness, or foreground and background, is helpful for entering and transitioning between bliss states.

In art, if there’s a portrait of someone. There’s a pretty face in the foreground, and perhaps there are some trees behind you. The face is the foreground, the trees are the background. There’s a similar concept in meditation of foreground and background: attention and awareness, respectively.

Attention is the foreground of your experience. You are attending to your breath or to your whole body or to the feelings of loving kindness in your body. You’re placing your attention on some aspect of your experience in the foreground.

Awareness is the background. It’s background awareness of everything in your experience: your body, your mind, and the world around you. That includes your whole physical and emotional and energetic body: every aspect of your body that you’re in touch with. It includes your mind, your state of mind: the thoughts and emotions you are experiencing. It also includes the space of the room that you’re in, any sounds that you can hear, and the temperature.

In The Mind Illuminated, Upasaka Culadasa defines mindfulness as “the optimal interaction between attention and peripheral awareness.”

You’re attending to your focus space, whatever it is – the sensations associated with breathing, a sound, the feelings of loving kindness in your body, anything – but you also have a broad awareness that includes your whole body, your entire mind, and all of space.

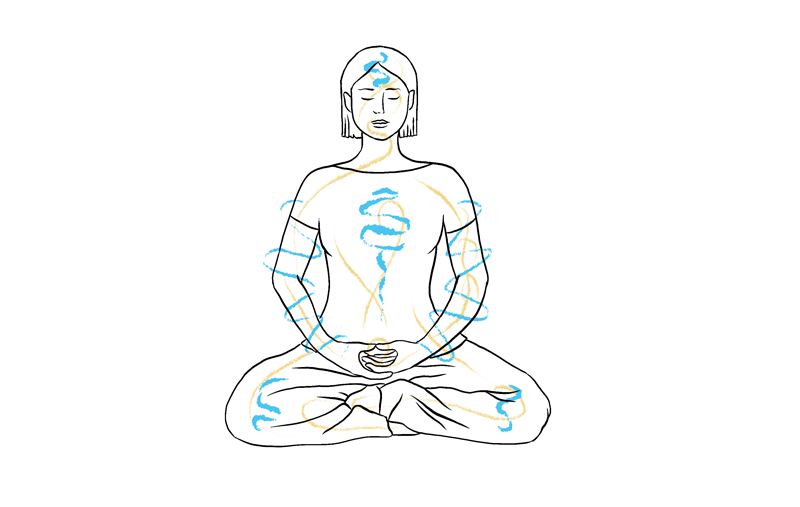

Whole body awareness is extremely important for jhanā practice. Be aware of and feel your whole body while you do a technique: not just spatially, but also qualitatively. You want to have an awareness that can notice phenomena like muscular tension or relaxation, or energy flow, or emotional blockages, and respond appropriately.

The Eight Jhānas

In this post, I’ll discuss two different models of jhāna practice: the traditional model (the Eight Jhānas) and the spectrum model.

In the Pali Canon, the oldest extant texts from the Buddhist tradition discuss the Eight Jhānas. These jhānas come in two sets: the first four (the form or rupa jhanās) and the second four (the formless or arupa jhānas). The major distinction is that the first four are states that you can get into, whereas the second four are described as being more like places or realms that you can go to. These states are qualitatively different: you’re entering a place.

In this post, I’ll mostly describe the first four jhānas, the form or rupa jhānas.

The sutras discuss various jhāna factors, which are conditions or circumstances that are necessary for the jhāna to arise. These include, for example, the absence of the hindrances, and the presence of mindfulness.

Although it’s useful to review the factors in depth for serious jhāna practice, in this post, I’ll discuss the two factors that are most useful to know about for entering the form jhānas: pīti and sukha. Pīti is usually translated as rapture, and sukha is usually described as happiness. I use the technical Pali terms, so you can recognize them elsewhere.

Pīti is more physical or energetic, whereas sukha is more emotional.

Pīti will show up in different ways for different people. It could feel like vibration, warmth, tingling energy. Often it can be very intense. It’s usually very enjoyable when you first encounter it, but often over time it becomes less enjoyable. Many people that do a lot of jhāna practice develop a distaste for pīti and its intensity.

Sukha is more emotional: it’s an emotional form of happiness. For me, I usually feel it around my mouth. That’s why it’s often a good idea to establish and maintain a smile while meditating – to kickstart this happiness, this sukha. You don’t need to maintain a smile if it’s hard, but you do want to go in the direction of emotional happiness, and smiling helps with that.

The simplest way to talk about the first four jhānas is whether pīti and sukha are present, and to what degree.

In the first jhāna, both pīti and sukha are present. However, the physical pleasure or intense pleasure in the body is more prominent. It’s in the foreground. You have your attention on the pīti. The sukha is actually pretty quiet and it’s in the background. You might not even notice it first, as it can be quite subtle.

In the second jhāna, these are flipped: both the pīti and sukha are present, but the sukha is more prominent. It’s in the foreground of your experience, whereas the pīti is in your background awareness. In the first jhāna, you place your attention on the pīti, whereas in the second one, your focus space is the sukha.

There’s also an important qualitative shift that happens between jhāna one and two. In the first jhāna, you can still have discursive thinking in the background, but in the second jhāna, thinking decreases dramatically to the point of there being no thinking. The mind gets very quiet. For me, it typically feels like it would be hard to think – like you could, but it would be hard to do so.

In the third jhāna, the pīti drops away — there’s just the sukha. With the pīti gone, it actually changes qualitatively to be more like contentment, rather than happiness or joy.

In the fourth jhāna, the sukha also drops away. There’s no sukha, and no pīti. It’s just equanimity, calm equanimity. This is also a form of happiness, but it’s not physical or emotional.

It’s typically accompanied by a sort of dropping sensation, as though you’re lower in the body.

In each jhāna, the focus space, what you place your attention on, changes: from the pīti, to the sukha, to the contentment, to the absence of both pīti and sukha.

To get into the first jhāna, you shift your attention from whatever the meditation object was – the breath, body sensations, metta, a sound – anything – to enjoyable sensations in the body. Then, you use your mindfulness of those sensations to generate pīti. That’s the first jhāna.

To get into the second jhāna, you shift your attention to the sukha; for the third, to the contentment (the sukha without the pīti); and then for the fourth, to the absence of both pīti and sukha.

Each jhāna is increasingly subtle. They’re less and less intense – but they’re also increasingly enjoyable, even though they’re quieter and more subtle.

These are the jhānas, described very, very briefly. But it can take significant practice and retreat time, and work with a qualified teacher, to learn to enter those four states.

The Spectrum Model

The spectrum model presents an alternative to the Eight Jhānas model, or other maps of the territory of bliss states. I first heard about this through Rob Burbea, but others talk about it as well.

This model is seeing jhāna as a spectrum of frequencies that you can tune your consciousness to.

It’s less that there are specific bliss states, which you are either in or not. Instead, there’s an attitude that acknowledges that there are many bliss states available, all of which feel good. They blend into each other, and there’s no real limit. So the only thing that makes sense to do is to explore.

This model is really helpful because one of the biggest hindrances to jhāna practice is essentially skeptical doubt in the form of asking, “Am I in it or not? Have I ever been in it? Am I good enough to get into it?”

All of that just isn’t very helpful.

Are you in the jhāna or are you out of the jhāna? It’s an irrelevant question, ‘in, out’ – where’s the intelligence here? The question is, what do I need to do at that point? What needs to happen?”

– Rob Burbea

With the spectrum model, you can take a different attitude. It’s like, “Hey, there’s just a lot of stuff out there and what I’m doing feels good right now. So I’m going to keep going.”

The spectrum model allows for increasing depth. Wherever you are on the spectrum, there are probably deeper states than where you’ve been. From that perspective it matters less if you’ve been in a particular state or not – you’re just like, “Hey, this was great! It felt good!” And you keep exploring.

When Rob Burbea talks about the spectrum model, he uses the metaphor of marinating:

marinating… means many, many times, over and over, just putting yourself, submerging yourself, and holding, sustaining something for as long as you can – hour, two hours, longer, three, whatever, four. Just sit in something, over and over and over. That’s going to be doing something to mind, heart, and body, that just won’t get the chance to happen if we’re sliding around too much.

…Marinating includes working, playing, tweaking. It doesn’t just mean kind of hanging out there in some kind of stupor or non-responsive, non-attuned, non-active playing way.”

When you get into these states, you just stay in them and enjoy them – you really just enjoy them, let them soak in.

From that perspective, the more time you can give to these kinds of practices, the more your nervous system is going to become accustomed to these bliss states, and the more that you’ll find yourself in them – and that will lead to more and more enjoyment, too.

Conclusion

Traditionally, you would use these states as the basis for insight practice and the search for classical enlightenment.

Many teachers say that entering jhāna is a requirement for a true and deep awakening. Of course, different teachers talk about awakening differently, and different teachers discuss jhānas differently, but learning and mastering these states are almost certainly helpful for going in the direction of classical enlightenment.

Awakening is said to be, amongst other things, the end of suffering. Reaching the end of suffering, being liberated from suffering, would be great- even better than the temporary bliss states.

Although awakening is considered the final goal of traditional Buddhist Practice, and the jhānas are useful for the search for enlightenment, it turns out they’re also useful for many other practices. I’ve found them to be extremely useful for doing Internal Family Systems / Parts Work, for example. They’re also useful for other contemporary psychotherapeutic methods, like the Ideal Parent Figure Protocol or The Bio-Emotive Framework, or as a complement to other spiritual methodologies like imaginal practice or Rob Burbea’s Soulmaking Dharma.

The Buddha said the only problem with jhānas is that they’re temporary. They’re wholesome, they’re beneficial, they’re enjoyable. He strongly recommended that you learn to do them and enjoy them.

However, they’re only states. They come and they go. But if you marinate in them, you can learn how to get in them at any time, and get in them more frequently. They become more common in your experience. They do still arise and pass away, fade in and out, but that’s the only downside.

I would encourage you to explore these states, to learn them and master them. It does take time and effort, it’s a real gift to learn these states and to discover this territory for yourself.

Resources

I would recommend engaging with these materials in the order presented in this section. These are presented in order of accessibility in terms of time needed + detail. Later materials contain similar information to the previous materials, but in more depth.

- How To Jhāna by Michael Taft

- Creative Samadhi by Rob Burbea (talk, ~57m; transcript)

- The Art Of Concentration (Samatha Meditation) Retreat by Rob Burbea (summary, transcript)

- Essence of Entering each of the 8 Jhānas by Leigh Brasington

- Right Concentration by Leigh Brasington (notes)

- The Mind Illuminated by Upasaka Culadasa, beginning with Appendix D

- Practising the Jhānas by Rob Burbea (notes, transcript – read the highlighted sections in the notes first and then dive in more if you are curious)

Thank you to Ted Holtz, Mark L, Leigh Brasington, and Daniel Thorson for helping me with my jhāna practice. Thank you to Nathan Hechtman for transcribing talks that led to this article, and to Vincent Li for editing this post.

The art in this post was created by Sílvia Bastos, and is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. You can support her work on Patreon.