Human civilization has developed a number of special organizations that train experts in specific domains.

If you want to train the world’s best cancer researcher, there is a long curriculum of medical study and practice ahead. If you want to train the world’s best astronaut, you should send them to NASA. If you want to train the world’s soldier, you should send them to an elite military training unit, like the Navy SEALs.

But what if you want to train extremely ethical, wise, trustworthy people? Where do you create those people?

It may not be obvious, but human society developed monasteries to serve this function.

At the Monastic Academy, we can take someone and dramatically improve their character. Moreover, we can take almost anyone – they don’t need to be extremely athletic or intelligent or have any special training. They just need a baseline of physical, emotional, and mental health. Give us a year, and we’ll do the job.

In this post, I’ll share a basic account of what a monastery is and why they are valuable. This account is informed by my time training at the Monastic Academy and its locations, as well as my intention to help this new monastic tradition flourish in the modern world.

Above all, in this post, I hope to destroy the straw man of a monastery in your mind, and replace it with a more useful conception. Monasteries are an underrated, cost-effective, high-impact solution to the biggest problems we face as a species and planet. Ignore them at our peril.

On Social Institutions

A monastery is a social institution, like a school, library, or post office.

Social institutions aim to provide value on two levels: they provide a value to the individuals who participate within them as systems, and they provide a value to the larger society. For example, a university provides an education to the students who study there, while providing educated individuals as well as a standardized system of accreditation for employers and other universities.

Monasteries provide a number of important functions for individuals: providing deep contemplative practice and support; providing training in ethical leadership; and serving as a safe, loving community in which one can live, grow, develop, and flourish. I share more about my own motivations for joining a monastery in Here to Serve.

In this post, I’ll focus exclusively on the value that monasteries provide to the larger society.

It’s obvious to most people what value universities, libraries, and post offices have as social institutions. This is because they are ubiquitous, and therefore well understood. Monasteries, however, are rare, and are therefore not well understood.

Most people have some sense that monastic training might be beneficial to the individuals who train there, even if they aren’t convinced, or aren’t interested in doing that training themselves. But it’s harder to grasp what value monasteries might have as social institutions.

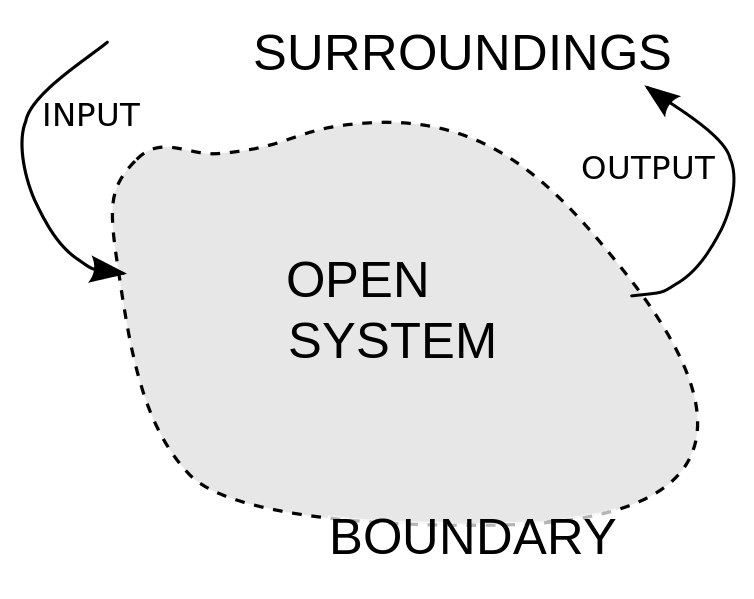

To understand this, we’ll simplify things by using a black box model.

The Black Box Model of Monasteries

A black box looks at a system in terms of its inputs and outputs.

Open system and io-flows by Krauss, CC BY-SA 4.0

Take a post office. A post office is a black box designed to deliver your letter. You put in a message, a stamp, and an envelope; then the message is delivered to a specific person or location. As a consumer, you don’t care how the post office does what it does. Of course, if you are a postal carrier or postmaster, you’ll need to understand the inner workings of a post office more clearly.

Here is a black box model of monasteries:

This model represents what we are explicitly trying to do at the Monastic Academy, as well as what I understand monasteries in general to be trying to do.

Inputs

A monastery takes three inputs: people, money, and land.

- People: Any individual who is genuinely interested in doing monastic training, and meets a baseline of physical, mental, and emotional health, will be a qualified candidate. Of course, different monasteries will naturally have different requirements, and if and when monastic training becomes higher-status and more competitive, those requirements might be raised. But the training should be valuable to anyone who meets these minimum requirements.

- Money: Monasteries use money to feed and house trainees; to build and maintain buildings; to run programs and events; and for various other expenses. Like other organizations, monasteries rely on the generosity of donors large and small. Fundraising efforts are constrained to – and work optimally with – ethical, relationship-based methods of resource acquisition.

- Land: Monastic training centers are normally located about 1-2 hours drive from a major city. By being near a major city, they can exchange people, resources, and ideas with the larger civilization. The distance allows a more natural, rural setting that affords trainees with the peace and quiet that are conducive to high-quality contemplative practice. Often, this location is supplemented by a “city center,” a smaller location within the city where a small team of trained monastics can run programs and events for the broader community.

Outputs

A monastery’s most direct output is creating trustworthy leaders. A community of those leaders, and the resulting culture, can lead to our economy and our species a whole becoming trustworthy.

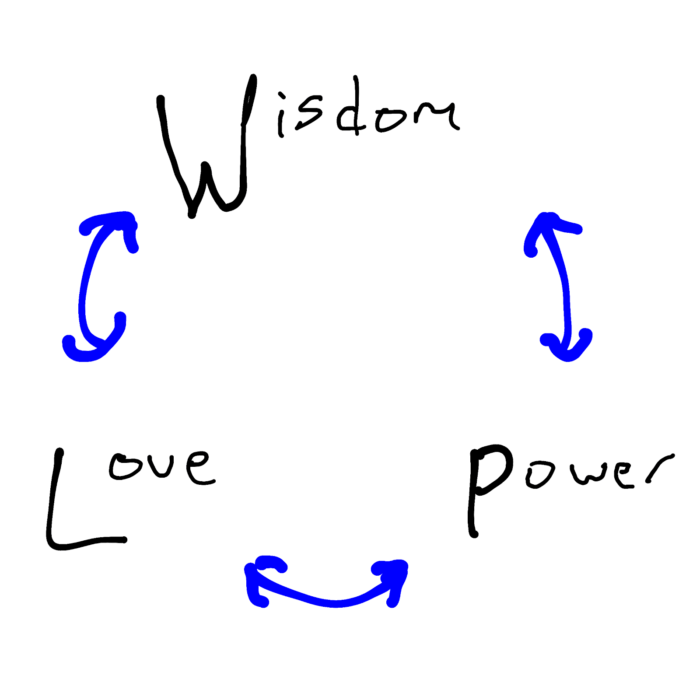

- Trustworthy Leaders: A trustworthy leader is an individual who has developed and integrated the skills of wisdom, love, and power; who uses those skills in a leadership capacity for the benefit of others.

- Trustworthy Community: A group of trustworthy leaders is a trustworthy community.

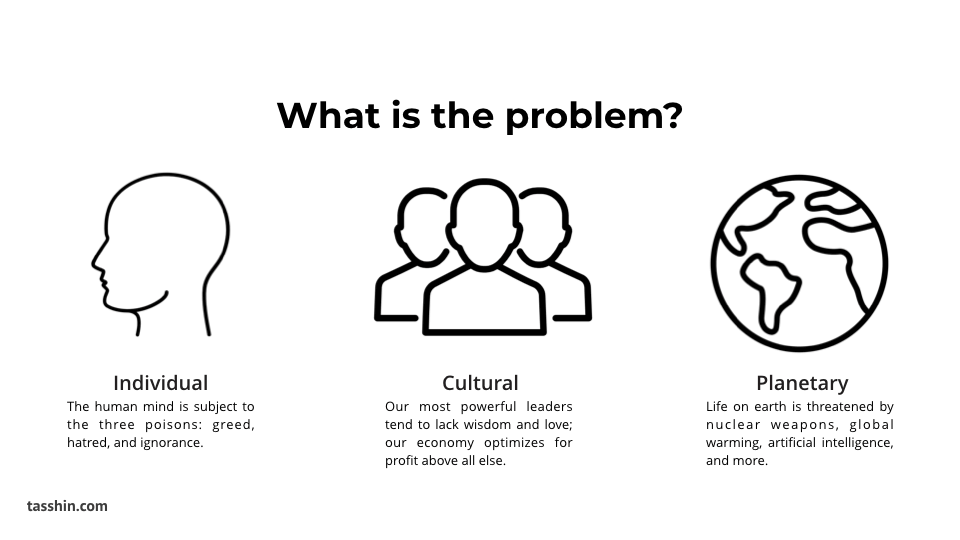

- Trustworthy Culture: When groups of individuals arise in community, culture is the combination of values, narratives, shared behaviors, and other intangibles that binds those individuals together. Our culture is untrustworthy, because it tends to select leaders who lack wisdom and love. A trustworthy culture would choose leaders who have the skills of wisdom and love in addition to power.

- Trustworthy Economy: Our economy is untrustworthy. It optimizes for profit, to the detriment of the individuals and societies within the economic system and the planet which supports it. A trustworthy economy would account for these externalities and optimize for human and planetary well-being. Bringing about a new kind of economy will require a new kind of leader and a new kind of culture as a pre-requisite.

- Trustworthy Humanity: Taken as a whole, we are untrustworthy at every level. This untrustworthiness has led to this time of crisis; we risk the destruction of our species and the planet. We need to turn around and find a new way. When we do, we will become trustworthy as a whole.

In other words, monasteries offer solutions to the individual and cultural scales of the problems we face collectively as a species.

Trustworthy leaders, a trustworthy culture, and a trustworthy economy are the necessary prerequisites for resolving the existential risks to our planet. Preserving our planet and life on earth is arguably the ultimate purpose of a monastery as a social institution.

The first output, a supply of trustworthy leaders, is the necessary precondition for the other outputs and the accomplishment of this larger purpose. Therefore, trustworthy leaders are the major, most direct, and most important output of a monastery.

Components

Naturally, different monasteries and traditions will have different ways of delivering trustworthy leaders. Here are some of the “components” our monastic tradition currently uses to create trustworthy leaders:

- Meditation: we make use of a shared curriculum and pedagogy; established meditation techniques; regular meditation practice periods and retreats; and 1-1 meditation instruction from a qualified teacher.

- Monastic Structure: a community with explicit shared values and ethics; hierarchy of leadership roles, which we regularly rotate people through; various rituals (e.g. chanting) and norms that afford coherence as a community.

- Work: legally, we are a non-profit organization; people receive various responsibilities for the maintenance of our non-profit, as well as training in those roles. People gain skill in areas like fundraising, productivity, and strategy as well as various competencies that might allow them to go on to work at or even found a non-profit, start-up, or another monastery.

- Personal Development: we frequently give and receive each other feedback on our actions, behavior, and ethics; we also periodically set aside time for formal peer-to-peer coaching.

- Interpersonal Practices: we make use of authentic relating, circling, contact improv, emotional processing, and other techniques for developing relational and interpersonal skills.

In my experience, this established – yet ever-evolving – combination of structures and practices reliably produces trustworthy leaders. When I look back at the people who I have trained with, it seems to me that 90-95% of them had largely positive experiences which benefited them. Most people seem to leave their training feeling happier, more fulfilled, and with a deeper connection to their values and sense of purpose.

Even more importantly, roughly 20% of those people have proved to be exceptional leaders. Our alumni have gone on to start non-profits, startups, and other projects; others have stayed within the monastic structure, founding new locations or assuming key leadership roles. Some alumni are increasingly well-known in their field of choice; others are quietly serving those around them. Regardless of their stature, the skills they have cultivated are the conditions for consequences that serve the world.

Conclusion

A monastery is a system that aims to produce trustworthy leaders, who can create a trustworthy culture and economy that is capable of preserving life on earth.

Different monasteries may be more or less effective at creating trustworthy leaders, in the same way that different universities may be more or less effective at producing students who are qualified in the discipline of their choosing.

Frankly, the relative obscurity and rarity of monasteries in our culture dramatically limits the ability of the monasteries that do exist to be effective at their purpose. There is some hope that this worrisome pattern is being reversed: partially because of Western culture’s recent, increased interest in meditation and mindfulness, and partially because of the renewed vigor our emerging tradition is bringing to contemplative practice and contemporary monastic institutions.

This variation in quality is why it is critical to cultivate an ecosystem of monasteries collaborating and competing with each other, so that they can help and push each other to be more effective than they would otherwise be.

Critical civilization-scale endeavors are bottlenecked by a shortage of qualified, trustworthy leaders. To the extent that monasteries deliver on their promise to deliver trustworthy leaders, they should not be underestimated as a solution to our biggest collective and planetary problems.