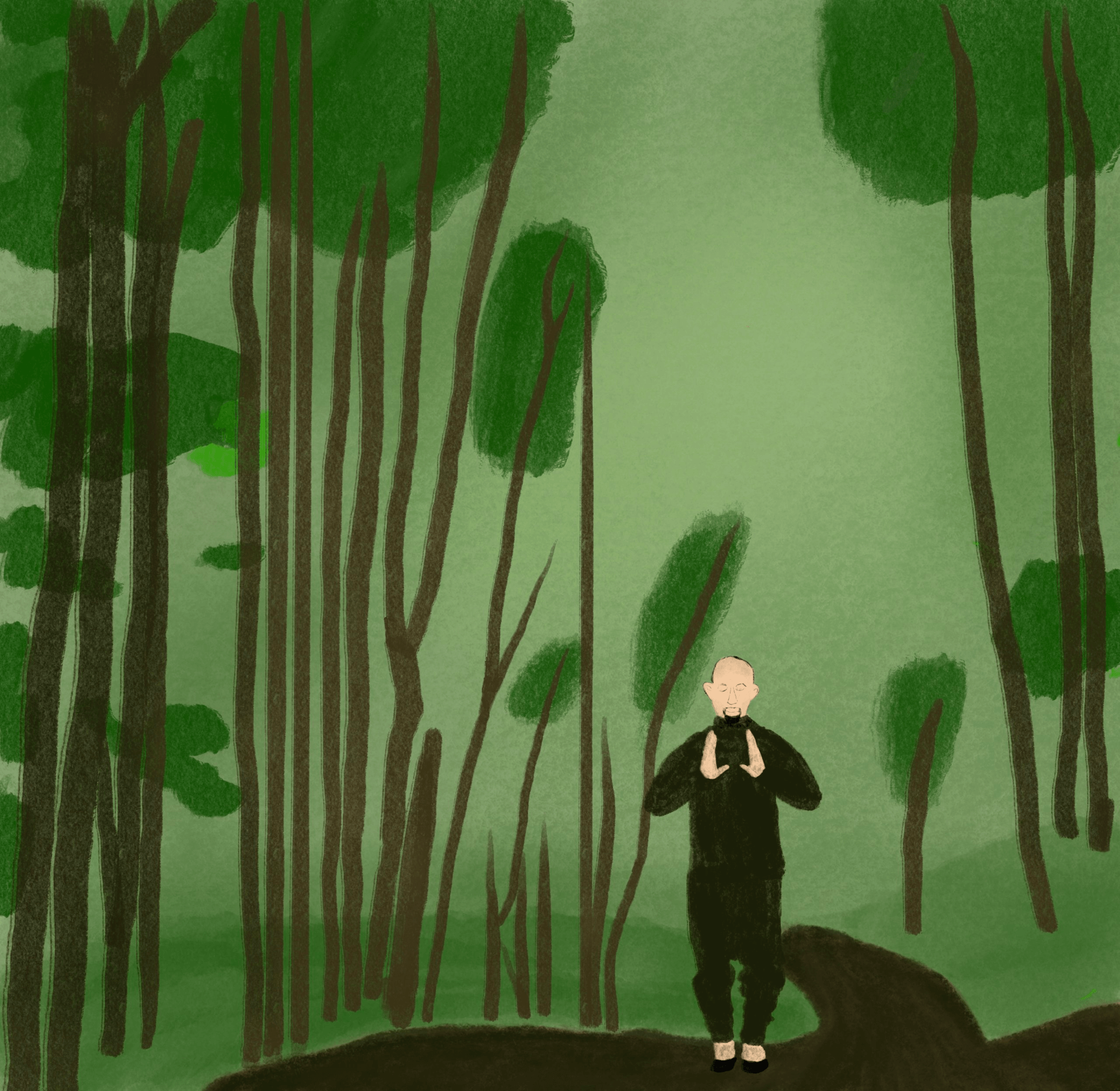

It’s a bright, warm winter day in New Mexico. The mornings and evenings are chilly here, but at midday, the sun is out and shining sweetly on my skin.

I’m standing in a field. In a few months, it will be flush with grass and vegetables, but for now, it’s dirt and dead grass.

I begin my daily Tai Chi practice with my hands in prayer over my chest. This isn’t traditional to the form I’ve learned – Sun style – but coming from a Buddhist background, it felt like a natural addition to my practice: a chance to remind myself of why I’m practicing, my connection to others, my desire to benefit the world.

Then I lower my hands, and stand in the initial posture. I take a moment to align my body – my head, my chest and shoulders, my lower back and hips, my legs and feet.

I also try to notice my internal state. Just like the weather outside, my internal experience is different from day to day. So in the same way that I might look outside a window to get a sense of the weather, and whether I should wear shorts and a t-shirt, or bring a raincoat, it’s useful to take a look and see how things are: how does my body feel, physically? How do I feel emotionally? Am I thinking? If so, about what? Do I feel present and collected, or distracted and far away? Is my awareness contracted and small, or broad and expansive?

Simply noticing these qualities helps them shift in positive ways – relaxing the physical body, or setting aside distractions and becoming more present. It also gives me a kind of “before and after” snapshot from practice, so I can notice how my bodymind feels after doing some Tai Chi, in comparison to how it felt when I started.

Then it’s time to begin the moving practice. Depending on my speed, the Sun Tai Chi form takes anywhere from eight to fifteen minutes. I typically practice at a moderate pace, not too fast, not too slow.

I move through punches and kicks, grabs and parries and deflections. My weight shifts from side to side in every direction. My hands move in coordination with my legs, the upper body flowing with the lower body. I try to coordinate the breath with the body.

I try to be as present as possible – to feel my body, to notice my mind, to keep my awareness expanded, to be present with as many moments as possible.

Some days, I feel awkward and clunky, like I’m a teenager again, finding myself in a new, bigger body that’s unfamiliar and hard to coordinate.

Other days, I feel smooth and graceful – the motion and the breath and my body feel like one unified whole, moving and swaying and flowing together, like a flock of birds or a concert at the symphony.

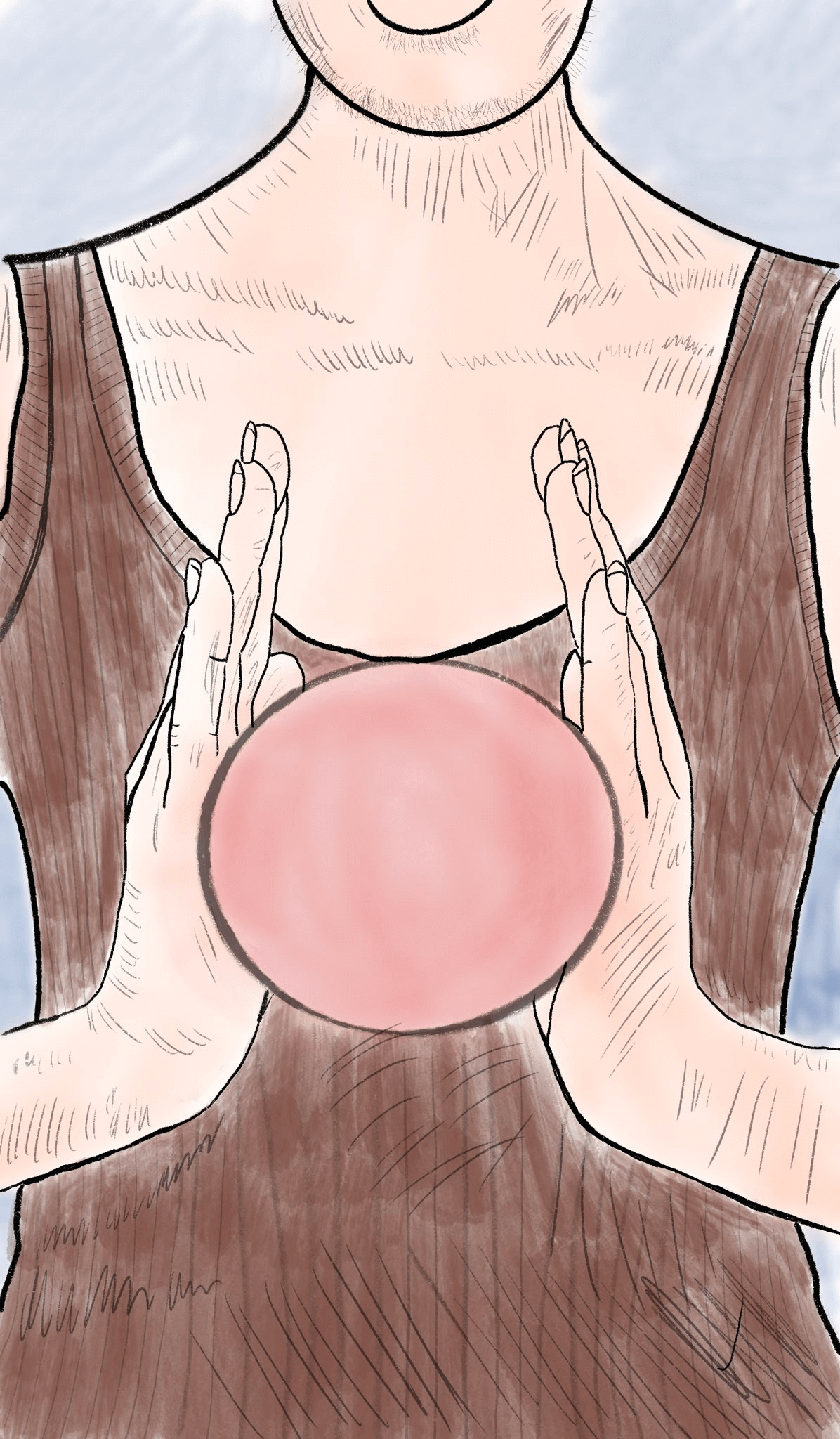

As I move my hands and my legs, as I twist this way and that, energy begins to flow.

I used to think energy was bullshit – but then I experienced it myself through meditation. It’s hard to deny when you’re feeling it pulse and move through your own body.

I’ve done a number of energy practices, but Tai Chi brings my energy body to life. It’s like doing a form of energy work on yourself. Moving through the sequence of motions inevitably causes energy to move through the body. Synchronizing the breath with the motions of the body increases that energy flow.

Regardless of the day, of how I feel showing up, of what my practice is like, I come more and more into my body. Even if I felt distracted at the beginning, I am more present by the end. To move through the form, I had to let go of any physical, mental, emotional, and energetic blockages that might have been present. I feel more relaxed and embodied, and more at home in the world.

As with most things in my life, I’m not an expert in Tai Chi. But the little that I know, and that I practice each day, has brought me great joy and many benefits.

Tai Chi and the Internal Martial Arts

I became interested in studying Tai Chi after developing a regular standing meditation practice (Zhan Zhuang). Traditionally, extensive standing meditation was a prerequisite for learning Tai Chi and the other internal martial arts. I found standing meditation so helpful for my contemplative practice and my health and well-being, that I became more interested in Qi Gong, Tai Chi, and other internal martial arts.

The distinction between external and internal martial arts points to the emphasis behind the techniques. Most martial arts have external and internal components, but different themes are emphasized in different arts and styles.

External martial arts are more about muscle power and physical force; the internal martial arts are more about body awareness and chi. There are three major Chinese internal martial arts: Tai Chi (Taiji), Xingyi Quan, and Baguazhang.

There are three main reasons people are typically interested in the Chinese internal martial arts:

- health: preserving and healing your health

- martial arts: self-defense, self-preservation, and possibly even attacking someone in combat or war

- spiritual practice: cultivating energy, body awareness, relaxation, and ultimately spiritual enlightenment

Regardless of your intentions and motivations, you get these three benefits from practicing the internal martial arts.

Traditionally, you’d study standing meditation (Zhan Zhuang), Qi Gong, and Tai Chi together. Tai Chi is different from Qi Gong, because Qi Gong is not martial, and it also has a wider range of motion and health effects. So, if you want the spiritual and health effects of then Qi Gong is more strictly on that side.

Because it’s martial, Tai Chi is limited in range of motion and kinds of the kinds of motions that you have because all of them have martial applications. Every move in the Tai Chi Form has a martial application; so even if it looks quite calm and graceful, it’s still usable in combat.

But it does have energy work that you’re doing and traditionally, you study them together along with standing meditation.

Learning Tai Chi

The Tai Chi form that I’ve learned is Sun Tai Chi (pronounced “soon”). There are many different kinds of styles of Tai Chi – with roughly five major forms. The other four most popular forms are Chen, Yang, Wu, and Wu (Hao) styles. Sun Style was developed by Sun Lu-tang, who lived from 1861-1932, making it the most recent of the five major styles.

Sun Lu-tang mastered Xingyi and Bagua before he studied Tai Chi seriously. He studied Wu Yu Xiang style Tai Chi from Hao Weichen. Sun Lutang eventually developed his own Tai Chi style, incorporating elements from Bagua and Xingyi.

Different styles have different appearances, weight distributions, frame sizes—as well as advantages, and disadvantages.

It took me about eight months of weekly online classes to learn the Sun Tai Chi form. I kept a journal thread on Twitter here. I had a one hour class each week, and would practice the form at least once daily (at least 10-15 minutes of practice). I also had the opportunity to have two in person lessons during that time.

If you were learning in person every day you could probably learn the form from a qualified teacher in two to three months, depending on how often you met, your aptitude, and other factors.

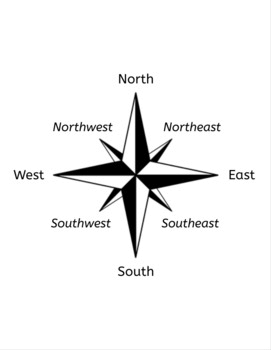

Instructions are given in terms of the four cardinal directions, with respect to your initial body position. You orient in all eight directions: north, south, east, west, northwest, southwest, southeast, northeast, and so on.

In general, when you’re learning it’s helpful to separate out the upper body motions from the lower body motions and then you put them together.

I have found it useful to think in terms of two kinds of instructional modes.

The first is where the instructor is procedurally stating what happens with the motion in acute detail, like “your right hand comes down and then the middle of your thumb is here.” There are a lot of details in the Tai Chi form and verbalizing them is helpful to know what you’re looking for.

The other one is inspired by Michael Ashcroft’s Fundamentals of Alexander Technique course and Perceptual Control Theory. Michael discusses a technique he calls Vishnu Hands. The idea is that you give your mind an image of where you’re going, and it can figure out on its own where it’s trying to go.

That method has been a lot more intuitive for me, especially with more complicated portions; but knowing the details is also really helpful.

Further Resources

Here are some recommendations about where to start with Tai Chi practice.

Ideally, you’d do in person training with a qualified teacher. But that may not be possible for you, either because there’s a global pandemic at the time of this writing, or because qualified teachers are rare.

However, online classes aren’t so bad! They’re certainly not as good as in-person lessons, but they’re not as bad as you’d think, either. I learned the basics of the Sun Tai Chi form virtually, although I’ve had the benefit of a few in person lessons, too.

I took weekly Sun Tai Chi Classes with Stanwood Chang. He began offering online classes during the pandemic, and has since ceased offering online Tai Chi classes, but still offers weekly Qi Gong Classes ($180/quarter). I had Stanwood on my podcast if you want to get a sense of him, of what he’s like and where he’s coming from (video / audio).

Tim Cartmell has also put out a set of DVD’s on Sun Taijiquan, as well as a textbook.

There are some other related classes online I’m aware of + could recommend as likely to be good even though I haven’t yet taken them myself:

- Tai Chi For Beginners: Online Course in Wu Style from Bruce Frantzis, $200

- Weekly Zhan Zhuang Classes with Corey Hess, suggested donation $20 / class

- Damo Mitchell’s Huang and Yang TaiJi Quan Program ($48 / month, $520 / year)

I’d also recommend these books as good reading:

- Josh Waitzkin’s The Art of Learning (for inspiration)

- Bruce Frantzis’ Tai Chi: Health for Life

- Bruce Frantzis’ Qi Gong: Opening the Energy Gates of Your Body: Qigong for Lifelong Health

- Master Lam Kam-Chuen’s The Way of Energy: Mastering the Chinese Art of Internal Strength with Chi Kung Exercise (about Zhan Zhuang/standing)

Thank you to Nathan Hechtman, for transcribing a recording that formed the basis of this article, and to A Lady on Fire and Vincent Li for providing feedback on this article. Thank you to Josh Waitzkin and Cameron Joyner for inspiring me to practice Tai Chi, and to Stanwood Chang and Tom for teaching me Sun style Tai Chi.

If you enjoyed this post, consider subscribing to my newsletter, my YouTube channel, or following me on Twitter to get updates on my new blog posts and current projects. You can also support my work and writing on Patreon.