- Meditation and Algorithms

- Optimizing Mindfulness

- The Distraction Algorithm

- Catalyzing Positive Behavior Change with Mindful Review

- Using Mindfulness to Practice Making Decisions

- Algorithmic Meditation Instruction

In the last post, we explored how to catalyze positive behavior change with a mindfulness-based meditation algorithm. In this post, we’ll explore how meditation techniques can improve our decision-making skills.

On Decision Making

If you’re like me, making decisions is hard. Small, moment to moment decisions aren’t so bad. I can figure out whether I want to order a salad or a pizza. Larger decisions are more challenging. There are many options, no clear-cut answers or simple heuristics, and the decisions we make will impact us for years and the rest of our lives. If we hesitate and procrastinate, we discover that inaction is its own kind of decision.

For others, making large decisions is easy, but small decisions are agonizing in painful. Either way, it’s in everyone’s best interest to learn to make better decisions. In the business world, for example, if you can make a better decision than a competitor, your company and the market will reward you handsomely.

Because making better decisions is so important, there is an abundance of best practices and effective methods for making better decisions. One good example is writing in a decision journal. Buy a notebook. When you make a big decision, get your notebook, and write down everything on your mind about that decision.

Decisions journal come from the work of Daniel Kahneman, author of the best-selling book Thinking Fast and Slow and winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics. Writing in a decision journal works because it counters the hindsight bias, the tendency to interpret past decisions favorably. If you use this method, you’ll make better decisions.

One thing to notice about this method is that it requires a notebook. Many decision making methods require physical objects as aids, like mind-mapping drawings, statistical software programs, or meeting procedures. These tools can be extremely useful in clarifying your thinking, but they do impose a constraint: the use of an external tool.

Some of our most important decisions happen in places or circumstances where we don’t have access to external tools. For this reason, and others, mindfulness skills are well-positioned to help us make better decisions in every situation.

Meditation might seem completely unrelated to decision-making, especially if you’re used to meditation techniques like following the breath or doing body scans. But with a system like Shinzen Young’s Unified Mindfulness, it becomes possible to combine the power of mindfulness with the process of making decisions.

Introducing the Decision Making Algorithm

The Decision Making Algorithm (DMA) is a meditation technique and decision making tool that I learned at the Monastic Academy. Soryu Forall, the founder and head teacher there, created it using Shinzen Young’s Unified Mindfulness. By combining mindfulness with the decision making process, you’ll make better decisions and improve your mindfulness skills.

When we make a decision, we do a combination of three things: we imagine the different alternatives, discuss them with ourselves, and consider how we feel about them. In other words, we experience + employ mental images, mental talk, and emotional body sensations during the decision making process. Let’s call these Image, Talk, and Feel. When giving advice, people say, “Follow your dreams,” “Listen to yourself,” “Trust your heart,” and other similar phrases. These suggest a fundamental trust of on mental image, mental talk, and emotional body sensations.

Most people value one of these senses above the others when making decisions, but they’re all valuable. The DMA helps us to notice and use each of these sense modalities when we make decisions.

Try The Decision Making Algorithm

Let’s give the decision making algorithm a try.

First, find a place to sit comfortably for a few moments. It doesn’t have to be the place that you usually meditate in, or anywhere special at all, although it might be easier to practice this technique for the first time in a quiet place.

You also don’t need to keep your eyes closed, or sit in a particular posture. You can sit with eyes open or eyes closed – eventually, with practice, you can do this anywhere, with any amount of time, even a short amount of time.

Additionally, you might find it useful to keep a notebook nearby to record anything that you discover, although that’s not necessary.

Having taken a seat, choose a decision to focus on. It’s okay to pick a small decision, and it’s okay to pick a big decision. You could decide what to eat for dinner, or mull over a thorny decision that’s been bothering you for weeks. As Shinzen says, “It’s all good.”

Frame your decision positively (“I will X”) and negatively (“I will not X”). For example, “I will eat pizza,” and “I will not eat pizza.” These two forms should be exact opposites; having them clearly defined is an important part of the rest of the algorithm.

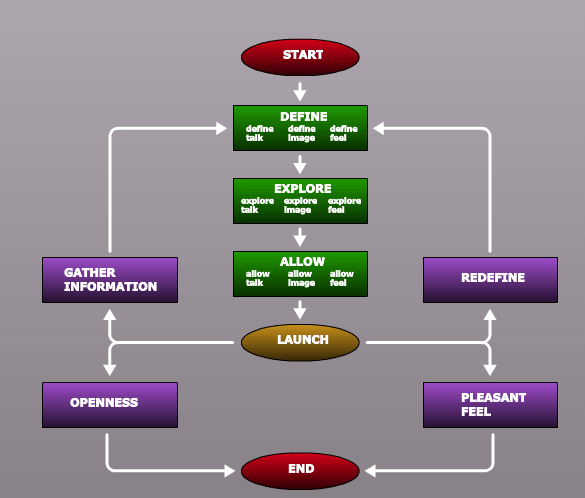

The algorithm has four steps: Define, Explore, Allow, and Launch. Remembering the acronym DEAL can help you to remember the process of using the Decision Making Algorithm. You can also print or copy a diagram like the one below, or use the website budsa.org for a guided experience (warning: requires Flash).

Let’s jump into the steps.

Define: Represent the decision both positively and negatively in Talk, Image, and Feel spaces. Talk about the option “I will X,” then talk about “I will not X.” Do the same for Image and Feel spaces. Imagine in your mind what “I will X” would look like, and then imagine “I will not X.” Feel what “I will X” makes you feel emotionally, and then feel what “I will not X” makes you feel. In each step, simply clarify what the decision is.

Explore: Actively investigate both sides of the decision in each space. Talk in more detail about “I will X,” and then “I will not X.” Then do the same for Image and Feel spaces, using your mind’s eye and your body’s emotional wisdom. Create a full decision that you are happy with.

Allow: Patiently allow each sense modality to add more to the decision, without trying to make anything happen. Hear if there’s anything your subconscious wants to say about “I will X,” and listen for the same about “I will not X.” Again, do the same with Image and Feel spaces. Allow anything to come.

Launch: This step means that we’re ready to finish. There are four possibilities, depending on what happened as you moved through the earlier steps.

If a decision has come, great! Focus on how good that decision makes you feel. Feel as good as possible about that decision – ideally, as many positive feelings as you felt negative emotions before you made your decision. This helps the process of making decisions to feel great, rather than just stressful!

If no decision has come, no problem. There are three options in this case.

You might want to change the decision. If so, start again, defining the decision differently.

You might need to gather more information about your decision. Determine how you’ll do that, and once you have the information, start again.

Lastly, you might not have a decision. You might simply not know what to do. Again, no problem. Simply halt the process. This is an opportunity to bring equanimity to the experience of confusion and not knowing. The decision making process often gives us the opportunity to directly cultivate this important skill.

As you learn, practice, and use this technique, you may have surprising results. Many people use it to make good decisions, and almost everyone finds it decreases the apparent difference between sitting meditation and the rest of their life. And almost everyone finds making decisions more meaningful and fun.

Subscribe to my newsletter, my YouTube channel, or follow me on Twitter to get updates on my new blog posts and current projects. You can also support my work and writing on Patreon.