Fundraising is one of the most powerful skills I’ve ever learned. I’ve raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for non-profit organizations, good causes, and personal service projects.

Knowing that you can raise money changes things. It changes the way you spend your time, and the kinds of projects you embark on or even consider possible. I know within my bones that if there’s a project or cause I believe in, I can raise money for it. I don’t need to have enough money. I don’t need to be rich. I don’t even need to have rich friends. If there’s something good that wants to happen, I can help make it a reality.

My friends and allies sometimes ask me for help raising money for their projects or organizations. I’m willing to help, but I prefer to teach people the skills of fundraising so that they can raise the funds they need by themselves. Teach a gal to fish, and all that.

In this post, I’ll share the basics of fundraising with you. You’ll need to put these ideas into practice to make them real, and to support the causes you care about. But this should give you a running start for making a real, meaningful, positive impact in the world.

- Limiting Beliefs About Money and Fundraising

- It Feels Good To Give

- A Buddhist Perspective on Generosity

- Philanthropic Giving and the Economy

- Fundraising is About Relationships

- Kinds of Fundraising

- The Right Fit

- Doing Your Research

- Making A Connection

- Cultivating A Relationship

- Making Asks

- Say Thank You

- Small Donor Campaigns

- Applying to Grants

- Leading A Fundraising Team

- What does a Fundraising Director do?

- Developing A Fundraising Strategy

- Managing A Fundraising Team

- Working With Team Members

- Conclusion

- Further Resources

Limiting Beliefs About Money and Fundraising

Learning fundraising showed me that I had limiting beliefs about money. I deeply believed in the causes I was raising money for. I wanted them to succeed. But I was scared to ask people for money. I would stress myself out in a whole host of ways. I was afraid that I’d be rejected, or judged. Deep down, I believed I didn’t deserve money, support, or even love.

Asking for money gave me the opportunity to face these limiting beliefs, and to update them with kinder, more realistic and more useful beliefs.

Over the years, I’ve come to see money as simply a form of power. It’s not intrinsically good or bad. It’s just a tool – one that can be used to benefit the world.

Many people have limiting beliefs about money. If you’re reading this post, it’s possible that you also have limiting beliefs about money. They might come up when you read this post, or try to act on the information within it. They might come up in the form of specific thoughts, or a difficult feeling – fear, or anger, or sadness, guilt or worry.

Unfortunately, the people with the biggest hearts and the most love for the world are often the ones who have the largest hang-ups about asking for money. If you have a project that you want to succeed, that the world is asking for your help with, then it’s worth looking closely at these beliefs and seeing if they’re really serving you and the world.

I don’t know what your exact experiences around money have been, but I can speak in general terms about the kinds of limiting perspectives people might have that prevent them from asking for and receiving the funds needed to make real, beneficial contributions to the world.

It’s easy to have a scarcity mindset around money. You see money as finite, worth keeping and storing. If you receive money, you are taking it away from someone else. You might see asking for money as rude or unkind. No one really wants to give money away – they just want to keep as much money as possible. If you do manage to receive money from others, you’re tricking them into giving it to you.

Some people even see money as an unfortunate, necessary evil in modern life, but evil nonetheless. They avoid dealing with, talking about, receiving, and using money as much as possible.

I’m expressing these beliefs explicitly and even hyperbolically to make a point, but these were more or less the subconscious beliefs that I held. I never thought these things explicitly, but I believed them subconsciously.

Subconscious beliefs can shape how we perceive and act in the world, and the realm of money is no exception. Our subconscious beliefs about money can shape how we see money, how we receive it, and how we use it.

Fundraising gives everyone this same opportunity: the opportunity to overcome your own limiting beliefs about money, and to support good causes that the world needs.

If we can see through those limiting beliefs, and find new ones, we will be able to ask for money for good projects with confidence, receive funds in abundance, and use them in increasingly beneficial ways.

It Feels Good To Give

A few different things helped me to see money and fundraising from a new perspective.

First, I thought about gifts that I made in the past. I thought about how I’d given money to the Wikipedia foundation in the past. I’ve benefited so much from Wikipedia. Wikipedia helped me in school, and in following my own curiosity. I’ve also benefited from other projects from the Wikimedia Foundation, like the Wikimedia Commons, Wikiquotes, and more.

Even though I only gave $20 or $50 to Wikipedia on a couple of occasions, I remember feeling so grateful to have a way to say thank you for all of the help I’d received from Wikipedia, and to help ensure that that same benefit would be available to others.

Once I remembered that memory, others flooded in. I remembered giving to the GoFundMe’s of friends, family members, and strangers who needed a helping hand. I remembered giving money to help start the monastery that I eventually trained at. And I remembered times that people had helped me, financially and otherwise.

I realized that it feels good to give money. It feels good! Think of when you think of a thoughtful gift for a friend or family member. Perhaps you like to paint with watercolors, and you paint a beautiful sunset at a nearby park for your friend. It feels exciting to make such a gift, and to give it to your friend. It brings you joy to make it for her, and to give it to her, and to see the joy it brings to her. It brings you closer together – it makes both of you happy.

The same can be true for making a monetary gift to a person or project you believe in. Giving money can feel just like giving a thoughtful gift to a friend or family member. It can feel good, and it can bring you closer to a person or project you believe in.

If you have money, you want your money to be used well. You see the power it can have, and you want it to be used as beneficial as possible. You want to give your money to people and projects that will be of benefit in the world. And when you do give your money away to a good cause, it feels good.

If you have money, you want to give a gift like that. You want to use your money to make a gift that feels good, that brings you closer to a person or project you believe in, and is beneficial for the world.

People want to see projects and people they believe in succeed in the world. It feels good to give money to make that possible.

From this perspective, money is never the point in a fundraising relationship. The point is what the money makes possible. Money fuels good projects with positive, beneficial impacts in the world.

A Buddhist Perspective on Generosity

As a Buddhist, I also realized that you can use money and making financial gifts as a way of practicing Right View and generosity (dana). Right View is the first step on the Noble Eightfold Path. When you make a financial gift, you are being generous; you are practicing Right View. It’s just one method for doing so, but it’s a powerful method.

One aspect of Wrong View is that “There is nothing given, nothing offered, nothing sacrificed” – that your actions don’t matter, that the act of giving money doesn’t matter, has no consequence or benefit (MN 117). This is Wrong View.

By contrast, one aspect of Right View is that “’There is what is given, what is offered, what is sacrificed.” (MN 117) Actions do have consequences. What you do matters. Gifts that you give have real, positive, beneficial impacts.

From this perspective, it’s good for people to practice generosity. It develops character and virtue to give money.

It’s a gift to give money. It’s a gift from the person giving to the person or organization receiving it. And it’s also a gift to the person giving, to have the opportunity to practice generosity, to develop virtue, and to feel good about making a gift.

If you see things this way, it has some unexpected consequences. It’s easy to avoid making an ask for a good cause because of various limiting beliefs or fear of rejection. But when we do so, we are denying someone the opportunity to make a gift, feel good, have a positive impact in the world, and to practice generosity.

From a Buddhist perspective, I would say something rather radical. I would say that if you had to choose between meditation and practicing generosity – and you don’t – practicing generosity might just be a more powerful practice for most people than seated meditation or any other formal contemplative practice. “Right view is the forerunner,” and practicing generosity is a direct means of practicing Right View (MN 117).

Philanthropic Giving and the Economy

Zooming out to see the macroeconomic view also helped to give me a new perspective on philanthropic giving. There is a tremendous amount of money in the world, and billions of billions of dollars are given away philanthropically each year. The following statistics are collected from the National Philanthropic Trust and the 2020 Nonprofit Employment Report from Johns Hopkins University.

In 2020, in the United States, Americans gave away $471 billion in philanthropic gifts. Individuals gave away $324 billion of those dollars. Other sources of charitable giving were by foundations ($88.55 billion), bequests ($41.91 billion), and corporations ($16.88 billion). Foundations are organizations dedicated to distributing grant funding to nonprofits; bequests are gifts made in wills after someone passes.

However, there’s also a huge number of non-profits which are actively doing fundraising work for their missions: there are over 1.5 million charitable organizations in the United States alone, which employ 12.5 million paid employees. While the non-profit sector isn’t traditionally considered an “industry,” these employment statistics make it effectively one of the largest industries in the economy.

Often, wealthy individuals and families create foundations that give away their money, or use something called a “donor-advised fund” (DAF). A donor-advised fund is an account administered by a public charity or financial organization to manage charitable donations.

In 2020, there were over 1 million donor advised funds, which held approximately $160 billion in assets, with an average size of $159,019. Annual contributions totalled $47.85 billion, and grants made from DAF’s totaled more than $34 billion.

This can be an alternative to paying taxes to the federal government – a chance to choose how their money is spent well, rather than acceding to the whims of the government.

These philanthropic organizations are actually legally required to give away a certain percentage of their money each year for tax purposes.

A foundation’s money is usually stored in the stock market. Provided the markets are doing well, they’ll see returns each year. That means they are usually making more money from the markets, and that the government requires them to give that money away.

So donors have money to spend, and they have to spend it, and want to spend it on good causes. The main question is, is your cause one they want to support?

Fundraising is About Relationships

Although it involves money and strategy, fundraising isn’t primarily about dollar amounts or project management. Ultimately, all of fundraising is about relationships.

You are a good person working on a project or cause that will benefit the world. You need money to succeed at your goals, and fundraising is a part of that process. To do that, you build relationships with people who believe in you and your project, who want to support you and are able to do so.

Donors want to see good things happen in the world, and can help make those good things happen. They believe in you and your project, want to support you, and are able to do so.

It’s important to develop an authentic, loving relationship with everyone you collaborate with to realize your vision for a better world. That means having:

- genuine interest in and care for others

- genuine authenticity in how you present yourself and your cause

- a personal and organizational commitment to ethics, honesty, and integrity

- remembering that money is a means to an end, and not an end in itself

If you build relationships with people that care about you, your desire to help the world, and the projects you’re building – if you take care to tend to your relationships with love and respect – then money will naturally come, and flow to where it needs to go.

Kinds of Fundraising

For fundraising purposes, I’ve found it helpful to distinguish between several different kinds of revenue:

- Program Revenue: revenue from events and programs that the non-profit runs and can collect revenue from – for example, through tickets, fees, etc.

- Grants: money from grant-making philanthropic organizations (foundations), usually but not always allocated for specific needs after an extensive application process.

- Private Donations: donations from private individuals, to a person or cause they believe in.

Each of these kinds of fundraising requires a different approach.

Some non-profits are sustained solely on program revenue. For example, some non-profits sell tickets to events or trainings, or sell decorations, artwork, or souvenirs related to their mission. The extent to which you need to raise funds from grants or private donations will depend on how much program revenue you can consistently bring in.

From one perspective, there’s no difference between large and small donations, or the approach you take to raising money. These are all generous gifts made by individuals that believe in you or your project and want to support you. You should build and maintain a relationship with your donors, regardless of the amounts they give.

However, in practice, it’s often useful to approach building and maintaining relationships with large donors a bit differently than you would when embarking on a small donor campaign. Of course, the specific strategies and tactics you’ll take will depend on your goals and context.

The Right Fit

My fundraising mentor, Scotty, always used the metaphor of a car key to define a good relationship between a donor and a non-profit.

There are billions of people in the world, with over a billion cars, and billions of car keys. But to turn a car on, you can’t just use any car key. You need the right car key – there has to be a fit between the key and the car.

It’s the same with cultivating a donor relationship. There are billions of people in the world, with trillions and trillions of dollars. But not everyone is going to donate to your cause. You have to find the right fit – between the donor, the amount, the project.

Establishing the right fit creates the conditions for good consequences: for your donor to make a gift, and for their support to make your project possible.

Fundraising isn’t just about making an “ask,” asking your donor for money. That’s actually a very small part of fundraising. Everything that comes before that is far more important: research, planning and strategizing, getting in the door, and building a relationship. If that’s all done well, then making an ask will be natural, easy, and successful.

Doing Your Research

Establishing a good fit begins with research. You need to build a list of possible donors to your organization, and learn as much as you can about them. This research aims towards understanding them better, and discerning whether they’re a good fit for your organization and project, or not.

If it shows that they’re not a good fit, that’s ok! But if your research shows that they’re a good fit, you’ll want to build a relationship with them.

As you do research, you’ll want to learn what you can about their financial situation, and their philanthropic history. What do they do for a living? Where does their money come from? What kind of organizations or causes have they supported previously, and why? What size gifts do they make?

However, money isn’t the only thing you need to learn about. You want to learn what you can about them, so that you can build a relationship with them. All kinds of information can be relevant and helpful: personal background, key interest areas, involvement in non-profits and other causes, religious or political affiliations, etc.

Research comes in many forms. You can find publicly available information about many donors with online search and various databases. You might find news articles written about your donors, personal websites, or websites for their philanthropic foundations.

You might also find it useful to ask around in your network to see what your colleagues, friends, and allies know about prospective donors. But it also comes from paying attention, keeping your eyes open, and listening closely to them when you interact with them.

Making A Connection

When you’ve done your research and found someone who you think could be a potential donor, it’s time to establish contact. You might already have a connection with this person – perhaps you’ve met them at a conference, or interacted with them on Twitter. If not, you can usually find a way to get in touch with them by being creative and resourceful.

Imagine that you’re running a non-profit that is promoting psychological well-being and awareness for astronauts. You’ve identified Elon Musk as a potential donor to your non-profit. Probably he would be excited about helping you with your noble cause, right? Well, how do you go about meeting Elon Musk? He’s a very busy person, who probably has people approaching him all of the time for all kinds of projects.

You need to “get in the door” – find a way to make a personal connection, and ideally to arrange a meeting (in-person being ideal).

This requires creativity, and depends on your context: who you are, who the person is, and who is in your shared network. Ideally, your research will have given you some clues as to shared connections that you have with them. Do you know someone who knows them? Do they have any upcoming events you can go to?

Here are some possible people in your network that might know how to connect to your potential donors:

- Board of Directors

- Team Members

- Professional Connections

- Other Donors

Cultivating A Relationship

Having a diversified portfolio of income streams will help you make your organization’s financial situation sustainable. For example, you might have a few large donors, many small donors, some grants from foundations, and revenue from specific programs. Your job is to see the big picture and move your project towards a more and more sustainable future. In any case, large donor relationships will likely form a critical part of any fundraising strategy.

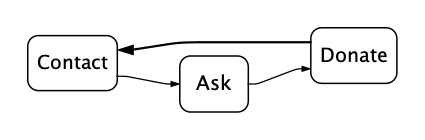

The Donor Contact Cycle

Ideally, each donor moves through a predictable cycle each year:

Contacting Donors

Contacting donors is all about building relationships. Each time you contact them you’re deepening your connection. Any kind of contact counts: it could be a phone call or email conversation, a video call or an in person meeting. It could be sending them a card for their birthday, or sending them a news article that you know they might enjoy (because you’ve done your research on who they are). If you’ve done your research, if you have developed a connection with them, that should give you ideas for how to contact them. Be creative!

The rule of thumb for contacting donors is “six to eight to cultivate.” That means you should aim to contact each donor six to eight or more times by phone, email, text, letter or other means before you plan and make an ask.

Don’t make asks with very few points of contact. One exception: if you already have many points of contact with a donor, e.g. a close family member or friend – you can make an ask on the basis of that existing relationship.

When you interact with donors, most of the conversation should be listening to them, learning about them, and what’s interesting to them. 80% of the conversation should be listening to them; 10% conveying about what you’re working on, and 10% learning how they feel about it.

As a rule of thumb, aim to contact donors once every four to six weeks. This should give you at least six to eight interactions with your donors every year.

Decide how people in your organization will contact donors. Who will proofread and approve messages? Who needs to read which messages? Where will donor contact notes be stored? Make policies that work for your organization’s needs. Be sure everyone knows these policies, and follows them every time.

Plan to visit donors in person whenever possible. The goal of each meeting is twofold:

- Convey what you’re actually doing to funders. Help them to understand what you’re doing. Share the mission and current projects with people in a way that’s compelling, interesting, that they feel grateful for.

- Learn what their interest level is through research and your questions. Which specific projects and initiatives are they interested in?

There are two measures of how a meeting is going / went:

- How much you enjoy talking to them. Enjoy connecting with them as much as possible. Usually this is easy since donors are interesting, wonderful, kind people!

- How much they’re talking. The usual error is to talk too much. If they’re talking, you know they’re interested.

Making Asks

Novice fundraisers often think that fundraising is just about asking for money. You can ask almost anyone for a small donation – say $20 or $100 – straight away. But if you’re seeking to raise larger amounts of money for your projects – perhaps tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, or even more – then making an ask is a very small part of what fundraising actually entails.

If you’ve done your research, made a connection, and cultivated the relationship, then you’re in position to make an ask – to make explicit requests for funds. If you’ve done your work well up to this point, making an ask is just a formality.

You are ready to make an ask when:

- You have had six to eight interactions or points of contact with a donor

- You have established that the donor has sufficient means, and how much they are likely to give

- The donor knows your larger mission, as well as current needs + projects

- The donor is excited about what you’re doing. Emotional engagement is critical. People want to feel good, important, connected.

- You know which projects or needs the donor is excited about

If you’ve done your preparatory work, you should know that a potential donor wants to give, what for, and approximately how much. They should already know what you need, and what their money will support. Simply schedule a call (or in person visit, or, if needed, send a letter), and make an explicit, straightforward ask.

Scheduling a Call

Send a short email saying that you’d like to set up a call. Include a personal note at the beginning if possible, and then say something like one of these:

- “I’d love to have a phone call soon to catch up 1-1 and also discuss ways you might support our organization. Could you talk between 10:30 AM and noon on Wednesday, 11/6, or between 10:30 AM and 1 PM on Thursday, 11/7?”

- “I understand you’re interested in our new project X. I have the sense you might like to talk about that, and I would too. I’d like to discuss your support of X.”

Explicitly mentioning that you’ll be asking for support for your project gives the donor a sense of what’s coming and a chance to prepare. It removes the element of surprise, and puts everyone at ease.

Planning the Ask

A good ask has several components:

- A vision of a better world that you believe in, they believe in, and your mission serves

- An immediate need that you have (“We need a new X / Y”)

- A specific amount, that they can give, which fits the need

- A clear connection between their gift and the solution to the problem.

A good ask makes the donor feel good, excited, connected, and grateful. Arguably, the emotional feeling is the real reason why most people give.

Deciding how much to ask for is one of the hardest parts of making an ask. You don’t want to ask for too much or too little.

A question to consider: in your mind, given what you know about them, if they really believed in what you’re doing, how much would they want to give?

If they are giving for the first time, it will be tricky to figure out what to ask for. In the best case scenario, you know how much money they typically give other organizations, and other relevant details. Many donors have a default gift amount, which they might have told you, or you may have learned through your research (e.g. through the tax information of their foundation). If you don’t know how much they typically give, you’ll want to give several options, typically a small, medium, and large option.

If they’ve already given in the past, be sure that you’re planning to make the ask at around the same time that they gave the previous year. Your goal should be to increase last year’s gift – if they gave $20,000, ask for $25,000. Gifts grow partially because the stock market usually grows year after year – but more importantly, gifts should grow because their trust in your relationship and your organization should be growing each year, too. Be sure that this ask, with its increased amount, matches a real need that you have.

It can be helpful to prepare by writing a solicitation letter. It helps you decide precisely how much you’re asking for, and for what. If you choose, you can use it in the meeting, to make the ask for you. You can send it to them the day before, or simply hand them the letter, and wait quietly while they read it.

Keep the letter short, ideally one page, with three relatively short paragraphs, or one long paragraph. Tell them what the project is; what is the need, the challenge your organization is facing (or the opportunity at hand), and how will this project resolve that; and how much it costs, including the total amount, amount raised, and amount remaining.

If you choose to share the letter, know that it has an emotional value for them. It puts them at ease regarding information. They can look at it later on, and spend this time connecting with you, a person they trust and like. Your meeting can be a connection session rather than an information session.

You may find it useful to write multiple versions, with different ask amounts or even projects, so that you can hand them a letter tailored to what they say in the meeting.

The Ask

When the time comes, you’ll have a phone call or meet in person. In some cases, you may need to make an ask by solicitation letter, but in person is the best of all.

This should be simple, straightforward, and explicit. They should know what the meeting is for, so you don’t have to worry. Just tell them why you’re calling! They want to know how they can help the work you both believe in.

Don’t hide your intentions. Instead, just be straightforward and honest. Tell them what you are asking for funds for, and how much you need. And then just ask: do you want to help? If they want to support your project, let them. If they don’t, no problem.

Following Up

Always send a thank you letter or email after you meet with a donor, thanking them for their time. Get to them as soon as possible.

If they agree to make a donation, make sure they have the information they need. How should they make a donation – should it be by check, or online? Do they need any special account information? Be sure to give them everything they need.

Asking for Contacts

If they’ve already given money, or have stated that they won’t give more, you can still ask them for further connections. Current donors are the best people to help you find further connections. This is still an ask, albeit a smaller one, so be sure you’ve had more points of contact between asks.

Say Thank You

Most non-profits don’t say thank you enough. As an organization, you want to thank your donors frequently, genuinely, and meaningfully. You’re thanking them for their financial gift, as well as for believing in you and in your mission, and for the impact their gift has made on your organization and project. Thanking donors helps them to feel appreciated for their gifts, understand how their gift is making a difference, and to be inclined to make gifts again.

All donors should be thanked within one day (24 hours) of receiving their gift. This can be as simple as an email or text saying that you received their gift, noting that you’ll send out a more formal acknowledgement letter within a day or two.

Research on fundraising at non-profits has shown that first-time donors who are thanked personally within 48 hours of their first gift are far more likely to give a second gift. It’s even better if this thank you is from a board member or other senior member of the organization.

Formal acknowledgement letters should include words thanking the donor, the date and amount of the gift (use the exact date and amount shown on the check), and sharing the impact their generosity is having. These letters serve to thank the donor, and also serve to document their gift for tax purposes.

For gifts made at the end of the year, you want to aim to send the letter out in the same tax year as the date of the check if at all possible.

It’s not possible to thank someone enough for their gifts. Say thank you, thank you, thank you, and thank you again. Here are some ideas of when to say thank you:

- Immediately after a gift (within 24-48 hours)

- After a meeting or visit

- At the end of each calendar year, stating what their gift has done

You also want to stay in touch after their gift. You want to continue the relationship – so you know what’s happening in their lives and they stay up to date on what’s happening with the project. Make sure you have a system for wishing your donors happy birthday; for congratulating them or sending condolences on special occasions, and for staying in touch. Be in touch with your donors regularly, perhaps every 4-6 weeks.

Maintaining relationships with donors is beneficial for multiple reasons. Donors want to hear how their money is being used, and to feel appreciated for their past contributions. Donors that have given in the past will likely be interested in giving again in the future. By staying in touch with past donors, donors can see that their money is being used well, and are more inclined to give again. This also makes organizational funding more sustainable and lasting.

Small Donor Campaigns

Even the smallest donation deserves gratitude and appreciation, because it comes from a place of generosity, and it helps to further your mission. A single small donation may not support a significant percent of your annual budget, but it is a meaningful and generous contribution nonetheless. Furthermore, from a practical perspective many small donations add up.

For most non-profits, small donations are also an important part of a successful fundraising strategy. Some non-profits and projects may even find it useful to focus exclusively on small donations.

For smaller projects (e.g. between $1,000 and $5,000) you can solicit small donations on an individual basis in much the same way as described as above.

For larger projects, it’s usually useful to plan campaigns for soliciting smaller donations from donors. Nonprofits can generally plan to run small donor campaigns 1-4 times a year. Combining large individual donations with small donor campaigns makes for a robust, resilient financial strategy for nonprofits.

To begin, pick a specific project or expense that you’re aiming to raise funds for, and an amount that you’ll need. Ideally, this is a timely, compelling need that is clearly related to your central mission.

While you can raise money for general operating expenses, it’s a lot more compelling to raise funds for a specific event, project, or need. “We need to raise $5,000 to run our annual winter soup kitchen event!” is a more compelling ask than “We need $5,000 to pay our electricity bill!”

Next, plan out how you’ll communicate the project to your donors. A website, blog post, or letter works well. What you write should contain:

- An inspiring story about your project

- A demonstrable need related to your mission

- A clear, specific ask for an amount of money

- A one sentence summary of the cause and ask

- Beautiful, inspiring pictures

- An easy way to donate

Here are some examples of letters I’ve written in the past:

You’ll need to distribute this document, so that others will see it. Brainstorm places and people to share it with, such as in-person communities, online groups, specific donors and supporters.

You might find it helpful for each person in your organization to write a personalized message that is authentic to them, their story and values, for them to share with their friends and family members who might be interested in supporting the campaign.

As the campaign progresses, update your team and supporters about the progress of the campaign, for example that you’ve raised half of the funds you are aiming to raise. It can be useful to make this information public and widely available (for example with a visual progress bar on your website), as a way to thank those who have already participated, and to inspire further support.

When you send out thank you letters acknowledging the gifts, mention how the contribution has helped towards reaching the goal of your campaign. If you still need more money to reach your goals, be sure to mention that. If you send an acknowledgement letter sufficiently quickly, people will often make another gift to help your organization meet its goals.

Applying to Grants

Applying to grants is another major fundraising strategy. There are a huge number of organizations that make grants each year.

There are two basic approaches to grant writing:

- quantity: send out a large number of grant proposals per year, based on a template or set of templates. Most of these grant applications will be copied verbatim from the templates, but you can spend ~1 hour adapting for each philanthropic organization.

- quality: select a few philanthropic organizations that relate to your organization’s mission, which seem likely to accept you. Spend a long time researching them, meeting the board members, and writing the application. The application should be extremely well-written, and customized to the organization. You will likely need changes to your projects to fit the grant and the philanthropic organization’s values and constraints.

Which approach you take will depend on your organization’s mission. A more common cause – like cancer research, or ending hunger – will likely have a wider pool of foundations that match their mission and projects. This makes the “quantity” approach feasible. A more specialized project will likely have fewer foundation matches, making the “quality” approach necessary.

If you do decide to pursue grants, ensure that the amount of time you spend writing grants makes sense based on how much you’re aiming for. You want to spend 10 hours writing a $10,000 grant application ($1k / hour); don’t spend 50 hours on a $5,000 grant.

If you receive a grant, stay in touch with the foundation. Foundations often have regular reporting periods where you need to tell them how you’re spending the money they gave you. They want to hear that you are using the money well, in line with the intended purpose you told them about, but also that you are learning from the work you are doing – that you are adapting to what’s working and what’s not, so that you can better serve the world. Show them how you’re learning and growing.

Staying in touch in this way prepares you to successfully receive future grants that you apply to. If you are eligible to apply for multiple grants, be sure that you do so for each grant-making period or at another interval. Even if you are not eligible, be sure that you’re talking with your contact person within the foundation about other opportunities to stay connected and support the larger cause.

Developing relationships with grant managers is similar to developing relationships with donors. Doing your research, ensuring a fit, cultivating a relationship, and contacting them regularly sets you up for success to receive grants.

Grant organizations often give to the same organizations year after year. Doing so is easier for them than having to vet new organizations to give to each year. Once the initial work of getting a grant has been done, it’s far easier to get future grants from the same organization than researching and applying for grants from new organizations.

Leading A Fundraising Team

I developed my skills in fundraising as the Fundraising Director and Assistant Director for a non-profit with a half million dollar annual budget. In these roles, I was responsible for the financial health of the nonprofit’s programs and overall operations. This required a larger vision and set of skills than fundraising alone, including productivity, strategy, and management skills.

In this section of this post, I will explain how to hold this kind of role in a non-profit organization.

What does a Fundraising Director do?

I’ve done fundraising work for the Monastic Academy, Dharma Gates, and several other smaller ongoing projects or one-off efforts, as well as for my own projects. At the Monastic Academy, I worked as the organization’s Fundraising Director, and I played a similar role in several other contexts.

Each of these projects has been different, with different missions and goals, strategies and tactics – but the basic principles of fundraising has stayed the same, as has the basic job description for a Fundraising Director. To succeed, you need to:

- Be familiar with each year’s budget: what the organization’s needs are, how much you’re aiming to raise, and how much actually needs to be raised. Be able to say something like “we need to raise $X-Yk this year” or “we expect need A to cost $B this year.”

- It is important to know how much different projects are currently estimated to cost. Work with those involved to learn the most recent information about these projects, as costs change (rise) over time.

- If you know the numbers, you will feel and project confidence and competence. If you don’t – not so much. You might want to create a “cheat sheet” for important numbers so you can review it regularly. It might look something like this:

- Last Year’s Revenue: $X

- Projected Revenue This Year: $Y

- Projected Costs For Project Z: $W

- Plan out how you’re going to achieve that: what income sources, connections, and strategies will be needed to raise the required funds?

- Maintain a shortlist of top donors: Become familiar with donors who have given in the past or might give in the future.

- Meet people: Develop existing relationships; meet new people (anyone you meet is potentially a funder, now or in the future), get people involved, get the right people to visit; create infrastructure for reliably bringing in new connections and income.

- Manage the team: Ensure that people interact with the donors so asks can be made. Manage “up” your bosses, and manage the team in executing the plan + achieving the goal.

- Make asks: Make asks of large donors. Bring in money for the operating budget and important projects.

- Advocating for the financial health of the organization: Knowing and improving the relative balance of income from each of the organization’s income sources; ensuring that you are not spending more than you earn; and advocating for acting on behalf of the financial health of the organization.

Three core skills are especially important to succeed at fundraising in a non-profit: believing in the project, management, and reading people.

Believe In The Project

Most people working in nonprofits believe in what they’re doing, but have difficulty speaking about it. You need to believe in the work you’re doing, and be able to speak about it.

If you don’t believe in what you’re doing, if you don’t believe that it is good for the world – and that financial gifts supporting the mission are of true benefit – then it would be out of integrity to work for that mission.

On the other hand – if you do believe in your organization, its mission and its work, then it’s helpful to be able to connect to those motivations and to share them with others in an inspiring way.

Management

As with any worker in an organization, you need to be able to plan and execute tasks, projects, responsibilities, and goals yourself. Productivity skills are extremely helpful for this. But you also need to manage other people’s tasks, projects, and responsibilities.

Reading People

Everyone gets frustrated when they feel missed or unseen. Donors are people, too. If your donors feel seen and loved, you will develop a strong relationship with them. This creates the conditions for good consequences with fundraising, of course; but it’s also a truly beautiful and connecting experience, which is intrinsically valuable.

Many interactions that involve money in our economy and world are transactional. I buy this, you give me that, and that’s the end of our interaction. It’s isolated, disconnected – cold. Done well, fundraising is about cultivating real relationships, with real closeness, real care, and real trust.

Responsibilities

You have various day-to-day, week-to-week, month-to-month responsibilities, including:

- Planning: assessing how you’re going to get to the yearly financial goals, building strategies

- Maintaining a fundraising schedule: who will you ask to give how much when? What are the probabilities that each ask will succeed?

- Managing the team: holding group and 1-1 meetings that empower team members to learn the skills and information that they need to successfully raise money for the organization.

- Interacting with donors: be familiar with who’s who. Meet existing donors and potential donors. Cultivating relationships, being in regular contact with people.

Developing A Fundraising Strategy

As the director of a fundraising team, an important part of your role is developing the overall strategy for how your team will be successful financially.

This begins with familiarizing yourself with your organization’s budget – what your organization spends, on what, and how much you will need to raise. Familiarity with the budget is not limited to the upcoming year’s budget – it’s also helpful to be familiar with past budgets, with historical spending in past years.

Then you need to make a plan for how you’re going to raise the necessary funds, whether your organization’s budget is ten thousand dollars for the year or a million dollars for the year. How did you raise funds in the past? Which individual donors or grant-making organizations made contributions? Are those donors likely to give again this year? Will you need to bring in additional funds from new donors, grants, or campaigns?

This is basically the same thing as being a financially responsible adult. As a homeowner, for example, you might say to your spouse: “next year, we’re going to need to pay $20,000 towards our mortgage, spend about $6,000 on repairs to our roof, and we’ll probably need to go in for a new fridge.” Then you look at the numbers, and figure out how you’re going to put the $30,000 together on top of any other ordinary expenses you might have, like food or gas.

In this process, it’s helpful to create a “shortlist” of major donors. You’ll iterate on this shortlist throughout the year, adding and removing donors as needed, updating their information, etc. You’ll also want to be sure that the whole fundraising team is intimately familiar with the shortlist.

This shortlist should track important information, including:

- Who each donor’s contact people are (ideally two contact people per donor)

- What need will you ask them to contribute to (a specific project? general operating expenses?)

- How much you will ask them for

- When you will ask them (dates are important – try to schedule asks around the time that a donor was asked previously)

- How likely they are to give that amount

Calculating Opportunity Value is especially helpful. Opportunity Value is the value you plan to ask for (e.g. $10,000) multiplied by an estimated probability (“we think there’s a 70% likelihood they’ll give again this year). That means that the value of a particular planned ask is worth $7,000.

If you calculate and regularly update the opportunity value for each ask your team plans to make, you can have a running estimate of the total amount your organization is expecting to bring in from major donor contributions. This is just a guess, of course, but it’s an educated guess.

It’s helpful to compare that educated guess of expected income with your budget. Ideally, your current educated guess based on individual opportunity values should add up to your goal. If your budget calls for a million dollars, but your team estimates you’ll only bring in $200,000 – then you can start making adjustments to your expenses, your fundraising efforts, or both.

Managing A Fundraising Team

You will need to raise at least tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars each year. In all likelihood, you can’t raise that amount of money by yourself. It takes a team.

Your job isn’t to raise the money yourself; your job is to manage the team so that you can raise the money together.

Meetings

You will need to hold and attend several different kinds of meetings with your team.

- Team Sync: This meeting usually includes some combination of training by lecture or exercise, status update about year’s fundraising efforts, and administrative reminders (“Make sure you put your notes in Salesforce”). Ideally, these meetings should be fun and inspiring.

- Work Meeting: A regular meeting with shared time to work on fundraising tasks. This meeting offers you a chance to help everyone move forward with the fundraising tasks they’re working on, and to assign new tasks/projects/goals.

- Ask regularly who has been contacted, and who contacted back

- Congratulate people when they complete their goals

- Help people set goals to accomplish before the next meeting

- 1-1 Meetings with Direct Reports: Spend time on 1-1’s for at least 15 minutes once a week. Use these 1-1’s as you see fit, perhaps with some combination of: checking in with people about any questions or concerns they may have; checking up on their projects + goals; supporting them in developing new skills that will help them with fundraising.

- Strategy Meetings: Schedule + hold meetings with various individuals and groups as needed. You’ll probably need to meet with senior leadership, any fundraising mentors or peers that you have, and any “task forces” that you assemble for e.g. grants.

Working With Team Members

Ideally, every team member would be involved with fundraising, and doing work that is well-suited to their skills, that results in a healthy flow of income. Moving in that direction will require thought, planning, and effort on your part.

Assigning Appropriate Responsibilities

Not everyone has the personality type for making big asks – typically folks who are outgoing, extroverted, enjoy connecting in relationships are well suited to making asks. Assign people to various responsibilities according to their skill. What will interest each person? What will challenge people at the appropriate level?

Managing Tasks and Projects

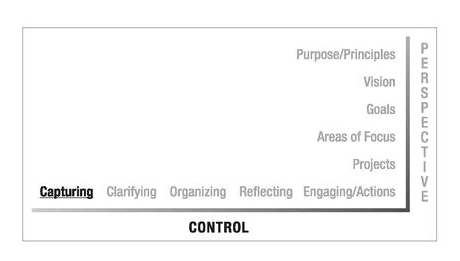

Know the difference between tasks, projects, areas of responsibilities, and goals (as described in GTD). You’ll need to assign people various responsibilities – knowing what kind will help you communicate expectations clearly.

- Tasks: one-off items that can be completed in a single sitting. E.g., “Call Donor Sue”

- Projects: collections of tasks that have a specific intention or outcome, usually associated with a deadline or timeframe. E.g., “Fundraising Trip to Boston”

- Areas of Responsibility: ongoing domains of responsibility, with standards of excellence to be maintained. E.g., “Fundraising” or “Fundraising Director”

- Goals: a specific objective to be obtained. E.g. “Raise $10,000”

Help people understand how their work fits into a larger picture, and to keep track of their work. Ask people what they’re working on, and what they have accomplished.

Training a Fundraising Team

Part of the reason to do fundraising is to help the organization; but working on fundraising also serves as a context for helping people to develop personally as leaders. Like all managers, your job is to help people succeed and grow. Primarily, you want people to grow skills in fundraising, productivity, and strategy.

- Use current needs and situations as a chance to train people in skills that they need to develop.

- Take time to learn about people’s life goals and consider how working on fundraising can support their goals. People do better work if they can see how it relates to what matters to them.

- If people care about the organization, and its contacts, then fundraising will be easy. If they don’t, then it will be hard. Help them to connect to why they care.

- Typically, people have strengths and weaknesses, and you’ll want to be aware of those weaknesses. For example, some people might tend towards sharing too much with their contacts (too friendly), while others might share too little (too professional). You want to build a relationship that is both friendly and professional, but not excessively warm or over-sharing.

- As discussed earlier, people have a lot of limiting beliefs and patterns around money. Once you’ve worked through your own limiting beliefs around fundraising, you can help others to work through theirs, too.

Managing Donor Relations

Mostly team members will be maintaining contacts with donors; your job is to manage the big picture of who’s being in touch with who, when, and why.

It’s helpful to track donor information, including research, points of contact, past gifts, and other relevant information. A CRM (customer relationship management) tool works well for this purpose. My personal favorite tool is Bloomerang, because it is designed for a relationships-first approach to fundraising (along the lines of this post), but I’ve also used Salesforce and a custom CRM in Airtable for this purpose.

Conclusion

Thank you to everyone who has ever made a contribution, financial or otherwise, to a project they believed in.

Thank you to every project, organization, or effort that has ever tried to make things better for others – for humans, for animals, for this planet.

May this post be of benefit to all projects that aim to be of service in the world.

May all good projects have the resources they need to benefit the world.

Further Resources

This post has been an extensive overview of what I know about fundraising, but it is by no means a comprehensive overview. Here are some suggested starting places to learn more about fundraising:

- The Soul of Money: Transforming Your Relationship with Money and Life by Lynne Twist

- Closing That Gift! by Bob Hartsook (notes)

- Nobody Wants to Give Money Away! by Bob Hartsook (notes)

- Bob Hartsook on Solicitation letters in Getting Your Ducks in a Row! (notes)

- Fundraising for Social Change by Kim Klein

- Management for Startups by Cedric Chin (notes)

Thank you to everyone who read drafts of this post and provided comments on it, and to Miran Lipovača, whose book Learn You a Haskell For Great Good! inspired this post’s title. Thank you to my fundraising mentors, Charles Scott, Judy Scott, and Soryu Forall, who taught me about fundraising while raising money for the Monastic Academy and other good causes. Thank you to Autumn Turley, who helped me to draft and edit this post; to Peter Xūramitra Park, whose assistance made this post possible; to Sílvia Bastos, for making this post beautiful and inspiring, rather than dry and boring; to PAN, who helped me cross the finish line after working on this post for over two years by meeting with me regularly, providing feedback and comments, as well as inspiration and accountability.

I wouldn’t have learned these skills – or have been able to pass them on to you – without the training I received from my fundraising mentors. If you found this post useful, consider making a donation to the Nature Conservancy or the Monastic Academy, the organizations that they raised funds for and are deeply passionate about.

The art in this post was created by Sílvia Bastos, and is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license. You can support her work on Patreon.

If you enjoyed this post, consider subscribing to my newsletter, my YouTube channel, or following me on Twitter to get updates on my new blog posts and current projects. You can also support my work and writing on Patreon.